Hungarian and Romanian Minorities in Ukraine: Conditions and Status*

This article continues examining a subject that is addressed in the previously published “Law of Ukraine ‘On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language’: The status of Ukrainian and minority languages.”[1]

Legislation recently been proposed concerning the future development of languages in Ukraine has been met with fierce dissent from both the Hungarian and Romanian minorities. In 2017 the Venice Commission strongly recommended that besides Ukrainian, the country should provide a substantial level of teaching in other official languages of the European Union, such as Hungarian and Romanian.

The paper presents an overview on the ways in which Hungarians and Romanians live their lives in Ukraine and how their fundamental rights are being respected (or not) in accordance with Ukrainian legislation. An analysis of the Hungarian minority describing its size and importance to Ukraine, being the fifth-largest national minority in Ukraine and the seventh-largest Hungarian diaspora in the world, is followed by an analysis of the Romanian minority. In particular, I will focus on the functioning of cultural and public organizations, mass media, and the rights of ethnic groups to be provided with an education in their native language, while concentrating on the political, social, and cultural rights of Hungarians and Romanians residing in Ukraine.

Hungarian minority in Ukraine

Ukraine’s Hungarian minority today is made up of 156,600 people, constituting 12.1% of the population of the Transcarpathian region.[2] In some cities such as Berehove and Chop, ethnic Hungarians make up almost half of the population, whereas many others settle in villages and work in the agricultural sector. On the outskirts of Berehove, the percentage of ethnic Hungarians increases to around 80%. Additionally, Hungarian minorities live in Uzhhorod, Vynohradiv, and Mukachevo districts, constituting slightly more than one-third, and almost 13%, of the population.[3]

At a local and oblast level, the Hungarian community enjoys a significantly strong representation. The chairman of the Party of Hungarians of Ukraine, Yosyp Borto, is the first deputy chair of the Transcarpathia Oblast Council.[4] Moreover, the Hungarian minority is the sole minority of all the national minorities in Ukraine that has created and consistently developed several political parties—the Party of Hungarians of Ukraine and the Democratic Party of Hungarians of Ukraine.[5]

Furthermore, during Ukraine’s last local elections on 25 October 2020, Hungarians aimed to distinguish themselves and therefore campaigned for the rights of national minorities. The Hungarian politician Péter Szijjártó, currently serving as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, called on the Hungarians of Transcarpathia “to support the KMKS Party of Hungarians in the elections” while also advocating for the incumbent mayor of Berehove, Zoltan Babiak. Additionally, Szijjártó, promised the Hungarian residents of Transcarpathia currently in Hungary that if they were to cross the border in order to vote in these elections, they wouldn’t be subjected to the customary 14-day Coronavirus isolation requirement.[6] Unsurprisingly, many interpreted his methods as interference in the Ukrainian elections, being “not only an attack on the Ukrainian elections but the audacity of the statement indicates that this is an attack on democracy itself in Europe, on its principles of respect and good neighborliness.”[7] An MP from the European Solidarity Party, Ivanna Klympush-Tsintsadze, called on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine to promptly respond, writing on Facebook that “appealing to Hungarians to support one of the political parties and/or a mayor in Transcarpathia, and doing so on election day, is an unprecedented act of contempt against a foreign state. This unacceptable behavior should be subject to the appropriate legal and political action.”[8] Although other national minorities are also represented in local governments, they do not have their own political parties, merely various public organizations.

Non-government organizations

The Hungarian minority is unquestionably the most progressive minority in establishing and promoting various associations and societies. There are twenty-eight organizations in the register of the Directorate-General for Justice in Transcarpathia oblast.[9] According to this data, there are twelve Hungarian organizations registered in Uzhhorod and eight others in Berehove and Mukachevo.

Moreover, the 81 organizations connected with national minorities that are functioning in Transcarpathia currently represent around 10% of all 827 registered institutions. NGOs are able to unite Hungarians for the reasons that they have a common culture, profession, occupation, and religion, etc.;[10] here are some examples:

• Association of Hungarian Librarians of Ukraine;

• Transcarpathian Hungarian Pedagogical Association;

• Hungarian Scout Association of Sub-Carpathian Ukraine;

• Association of Transcarpathian Hungarian Entrepreneurs;

• Association of Transcarpathian Hungarian Journalists;

• Association of Hungarian Culture of Transcarpathia; etc.

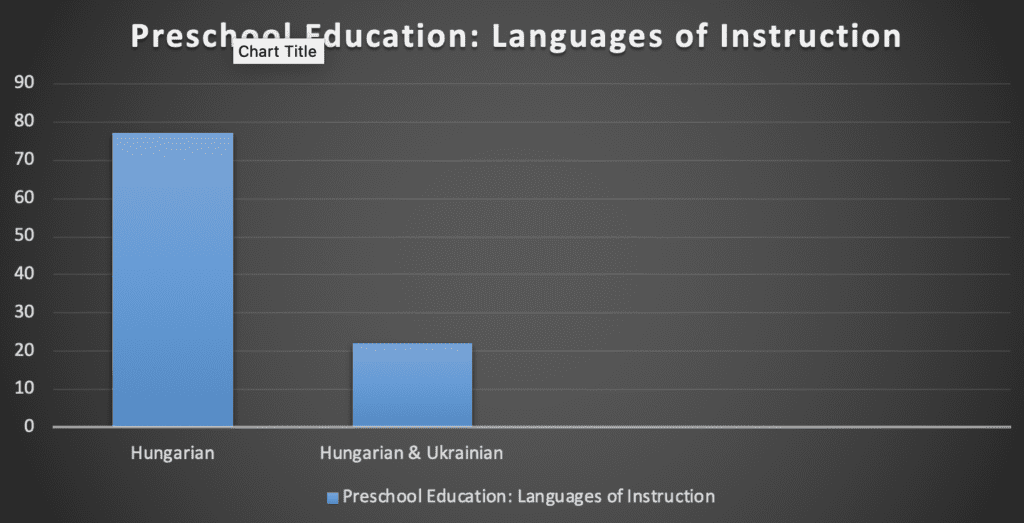

According to the Constitution of Ukraine, the Ukrainian language is recognized as the only official language in the public sector.[11] However, citizens who belong to national minorities are guaranteed, in accordance with the law, the right to receive teaching in their native language or, alternatively, to study their native language at state and community educational establishments and/or through national cultural associations. At the level of preschool education in Transcarpathia oblast there are 77 institutions where education is provided exclusively in Hungarian and 22 which teach in Hungarian and Ukrainian—both of which total only 16.8% out of all kindergartens[12] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preschool Education in Transcarpathia oblast: Languages of Instruction.

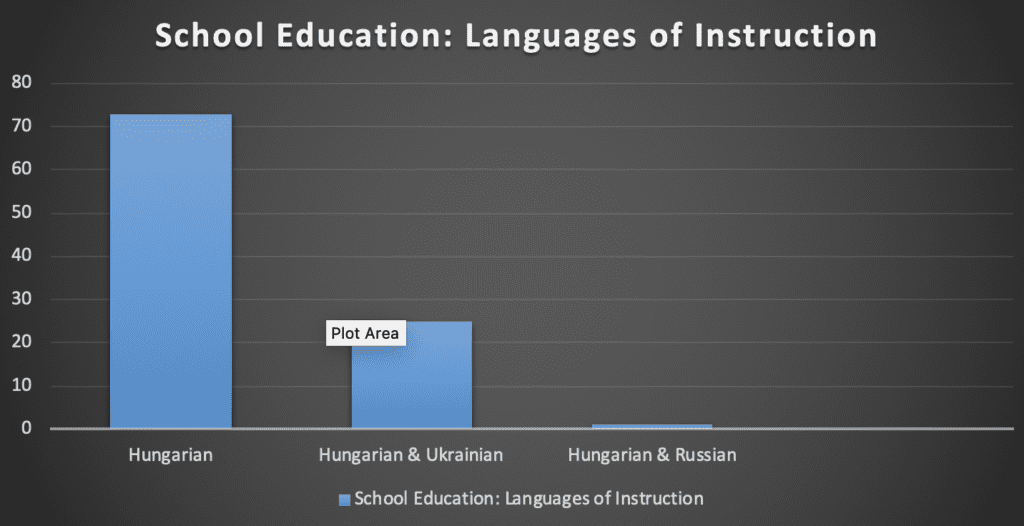

In Transcarpathia oblast there are 73 educational establishments (68 state-run, 5 private) where education is conducted exclusively in Hungarian, 25 in the Hungarian and Ukrainian languages, and 1 conducted in Russian and Hungarian (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Secondary school Education in Transcarpathia oblast: Languages of Instruction.

Therefore, the law which grants Hungarian minorities the right to receive an education conducted in Hungarian is implemented at only 15% of the schools in the region. Meanwhile, importantly, this minority is demonstrating its proactive position by opening private schools (the first one was opened in 1995).[13] Although limited, a post-secondary education taught in Hungarian can be obtained, but only at the University of Uzhhorod. There is also the private Ferenc Rákóczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian Institute in Berehovo (founded in 1994, currently with 1,100–1,200 students studying there).[14] In fact, the Hungarian minority is the only minority in the region that has its own tertiary education institution offering study in its own language.

Thus, Hungarians in Ukraine have created a complete cycle of national-language education, from kindergarten to the Ferenc Rakoczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian Institute, and this influences the community’s general willingness to pass Ukraine’s IKA.[15],[16] Yulia Tyshchenko, a UCIPR expert, explains: “Hungarian schools in Transcarpathia strongly resist any implementation of parallel teaching in Ukrainian and Hungarian. The reason being that Hungary has an already established system of supporting teachers and children who attend the Hungarian-only schools.[17]

| Language of the Edition | Number of Printed Titles | Number of Copies |

| Ukrainian | 16,857 | 52,513,200 |

| Russian | 3,449 | 5,424,500 |

| Hungarian | 33 | 37,900 |

| Romanian | 56 | 96,000 |

Figure 3. Book publishing in Ukraine, 2019.[18]

Figure 3 shows statistics for book publishing in Ukraine in 2019. The majority of the books and brochures (52.5 million) were published in Ukrainian, with around 5.5 million in Russian, only 37,900 in Hungarian, and 96,000 in Romanian. The large volume of books published in Romanian is explained by the existence of the publishing house Bukrek in Chernivtsi. In 1997, Bukrek released the first Romanian alphabet book, a “becedar,” in independent Ukraine.[19]

Additionally, a considerable amount of work has been undertaken in order to develop and provide textbooks for educational establishments as per to the New Ukrainian School program.[20] Textbooks for grade one students have been translated into the national minority languages of Ukraine (Polish, Russian, Romanian, Moldovan, Hungarian) in order to provide equal access to high-quality education. These translations include state-approved textbooks on topics such as mathematics, exploring the world, art, etc.

The Romanian minority in Ukraine

The Romanian minorities in Ukraine live predominantly in the territories of Northern Bukovyna (Chernivtsi oblast), Transcarpathia oblast, and Budiak city in Odesa oblast.

According to the last official census (conducted in 2001), the Romanian minority comprises 151,000 citizens, with recent data indicating that the composition of the Romanian population has remained stable[21] at 12.5% in Chernivtsi oblast and 2.6% in Transcarpathia oblast of their respective populations. In Trascarpathia oblast (Ukr: Zakarpattia), citizens who belong to the Romanian minority mainly live in Rakhiv (11.6%) and Tiachiv (12.4%) districts. Predominantly they speak Romanian (around 90% of people) and take full advantage of their right to receive an education in their native language.[22]

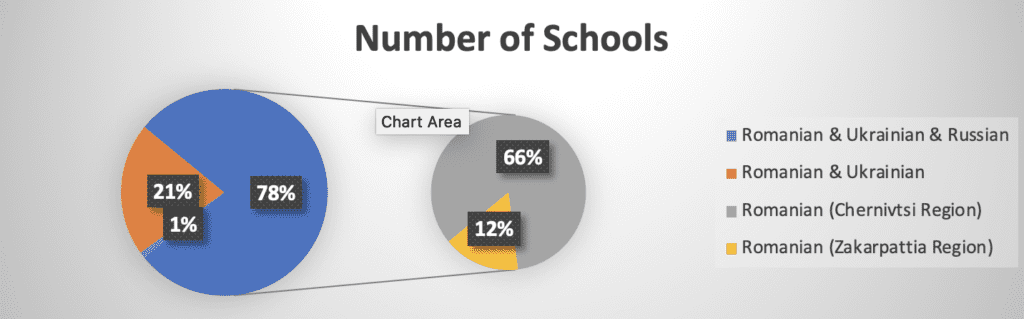

When considering pre-school education, 60 kindergartens in Chernivtsi oblast (3,206 children) were taught in Romanian in 2016.[23] The data for 2018 suggest that the number of children increased slightly (to 3,312).[24] Thus, just over 10% of all children in Chernivtsi oblast receive an education in Romanian. As for elementary schools, in the 2016/2017 academic year there were in total 75 Romanian-language schools (63 in Chernivtsi oblast and 12 in Transcarpathia), 20 schools offering study in both Romanian and Ukrainian, and one institution providing three languages of study—Ukrainian, Romanian, and Russian (see Figure 4).[25] In 2018/2019 there were 69 Romanian-language high schools[26] and 68 in 2020.[27]

Figure 4. Education system: Elementary school education for the Romanian minority.

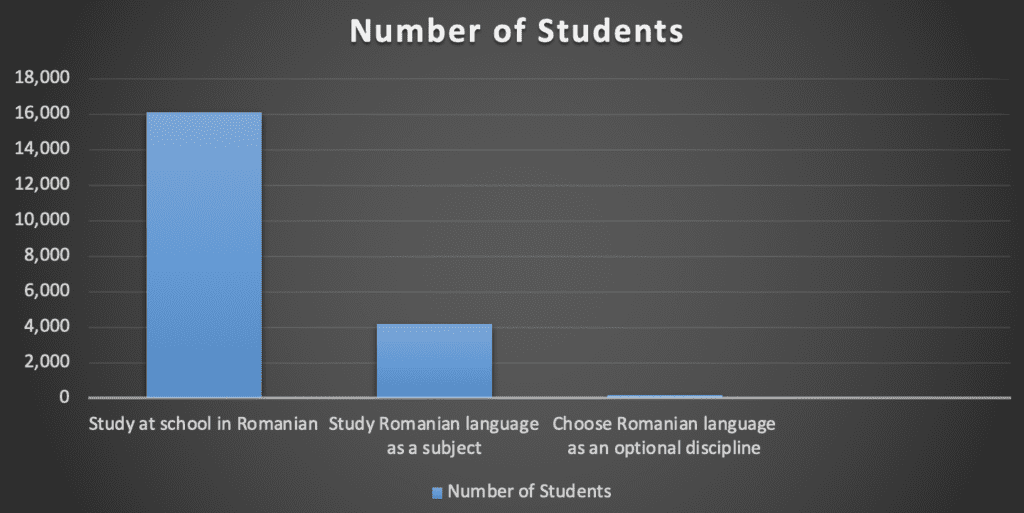

Figure 5 (below) demonstrates that 16,339 students study in Romanian at schools, 4,182 pupils study the Romanian language as a subject, and 178 students chose Romanian as an option.[28]

Figure 5. Number of students that study Romanian language.

There exists an undeniable imbalance between learning the official language of Ukraine (Ukrainian) and learning the languages which belong to national minorities. Ukrainian officials have consistently emphasized that those of certain minorities are more likely to achieve significantly poorer IKA results, which consequently subjects them to far more difficulty in achieving a respectable career in Ukraine.[29] For example, 67% of students who attended the Grigory Nandrish Magyar Secondary School were not able to pass the mandatory Ukrainian language test.[30] Similarly, at the Romanian-language school in Malynivka, approximately 75% of students failed the Ukrainian language test, with a pass rate of only 12.5%.[31] Those pupils who were unable to achieve the required results lose the opportunity of enrolling in higher education programs at Ukrainian universities. This is one reason why the “Law on the State Language” is so important. By insisting that national minorities learn the state language, they can have better future opportunities and an easier and more enjoyable integration into the Ukrainian society where they live.

The various issues related to protection of the cultural rights of national minorities are broadly addressed at the level of local programs. According to the Chernivtsi Oblast State Administration (ODA), there are 15 Romanian national-cultural societies in the region. Moreover, financial support is given to the following associations from the Chernivtsi ODA for operational purposes:[32]

- Bukovinian Art Center for the Revival and Promotion of Romanian Traditional Culture;

- Golgotha Romanian Association, an oblast-wide NGO;

- M. Eminescu Society of Romanian Culture;

- George Coşbuc Socio-cultural Association for Newcomers in Transcarpathia;

- Ioan Mihaly de Apsa (Apsa de Mijloc) Cultural Society;

- Uniunea Regională a românilor din Transcarpatia “Dacia” – Apsa de Jos;

- Speranţa NGO.

In Chernivtsi oblast, legislation allows representatives of national minorities the opportunity to create and use print media. The most popular periodicals are:

- Concordia

- Zorile Bucovinei

- Arkashul

- Libertatea Cuvântului

- The newspaper de Gertsa (Rom. Herța)

- Septentrion Literar

- Familia

- Bukovyna Bell

Additionally, it must be pointed out that Concordia is financed from the state budget and Zorile Bucovinei[33]and de Herts from the local budget.On another note, the TV channel UA: Bukovyna, which belongs to the National Public Broadcasting Company of Ukraine, produces five television programs and eight radio broadcasts in the Romanian language, without translation or subtitles, in order to help the Romanian-speaking minority stay up to date with world events.[34]

Conclusion

In sum, although the Hungarian and Romanian minorities in Ukraine strongly opposed the Law “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as a state language,” my research clearly demonstrates that with the help of national cultural associations and institutions, Hungarian and Romanian national minorities have kept protected their rights to study their native languages at preschool and school institutions.

Representatives of the national minorities actively work in public administrations in order to ensure the safety and security of their rights—especially the Hungarian minority, which even has multiple independent parties. Furthermore, national minorities have their own printed media, some of which are financed by the state or local budgets of Ukraine. In the publishing sphere, there are books published in Ukraine’s national minority languages, as well as state-sponsored publications and textbooks used for educational purposes in schools.

According to the new language law, media outlets are obliged to produce a certain percentage of their content in the state language of Ukraine, while all higher educational institutions must have the capacity to teach indigenous languages to all students who express a desire for it.

The law also stipulates that language courses must be available in the languages of ethnic minorities in Ukraine, and for the first time in Ukraine’s history, Ukrainian sign language has been provided the necessary protections and support.

Overall, the Hungarian and Romanian languages are actually strongly protected by this Law. In a number of provisions, they are protected as a national minority language, and in other provisions they receive preference as official languages of the European Union.

Critics have claimed that by design or not, Hungary’s opposition to the Ukraine’s law on the state language nevertheless plays into the hands of Russia. Certain research shows that this problem has been exacerbated, particularly since Russia’s occupation of Crimea and territories in the Donbas. Upcoming research will be devoted to investigating the problems and prospects which have arisen and will yet arise due to the Russian minority in Ukraine.

[1] https://ukrainian-studies.ca/2020/10/20/the-official-act-on-the-state-language-entered-into-force-on-16-july-2019-the-status-of-ukrainian-and-minority-languages

[2] “Ethnic and language composition of the population of Ukraine”; 2001 Census, http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Transcarpathia Oblast Council (7th Convocation). URL: https://zakarpat-rada.gov.ua/oblasna-rada/kerivnytstvo-rady/pershyj-zastupnyk/biohrafichni-dani/

[5] Hungarian parties: List of candidates for the Transcarpathia Oblast Council https://zakarpattya.net.ua/News/73839-Uhorski-partii-Spysok-kandydativ-mazhorytarnykiv-do-Zakarpatskoi-oblrady

[6] https://www.facebook.com/szijjarto.peter.official/posts/209477177211507

[7] https://www.facebook.com/1200324595/posts/10224221241137627/

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Directorate-General for Justice in the Transcarpathian region. URL: https://pzmrujust.gov.ua/

[10] Belei, L. (24 of January). National minorities of Transcarpathia: to bigger – more, to smaller – less. URL: http://uchoose.info/natsionalni-menshyny-zakarpattya-bilshomu-bilshe-menshomu-menshe/

[11] Constitution of Ukraine. URL: https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/constitution

[12] Belei, L. (24 of January). National minorities of Transcarpathia: to bigger – more, to smaller – less. URL: http://uchoose.info/natsionalni-menshyny-zakarpattya-bilshomu-bilshe-menshomu-menshe/

[13] Belei, L. (24 of January). National minorities of Transcarpathia: to bigger – more, to smaller – less. URL: http://uchoose.info/natsionalni-menshyny-zakarpattya-bilshomu-bilshe-menshomu-menshe/

[14] Ferenc Rákóczi II. Transcarpathian Hungarian Institute II http://kmf.uz.ua/en/

[15] IKA stands for independent knowledge assessment

[16] They do not understand: Ukrainian Hungarians and Romanians in the schools practically don’t study the state language.

URL: https://texty.org.ua/articles/82794/they_do_not_understand_ukrainian_hungarians_and-82794/

[17] Ibid.

[18] Issue publications in Ukraine in 2019 http://www.ukrbook.net/statistika/statistika_2019.htm

[19] Bukrek Website: http://www.bukrek.net/index.php/en/about-us

[20] The New Ukrainian School is a key reform of the Ministry of Education and Science. The main objective is to create schools that will be attractive provide students not only with knowledge but also the ability to apply it in real life. The New Ukrainian School has a new approach to students. Their opinions are respected, they are taught to think critically, not to be afraid of voicing their view, and to be responsible citizens. Parents also like this school because cooperation and mutual understanding prevail. URL: https://mon.gov.ua/eng/tag/nova-ukrainska-shkola

[21] “Ethnic and language composition of the population of Ukraine”; 2001 Census, http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/

[22] Belei, L. (24 of January). National minorities of Transcarpathia: to bigger – more, to smaller – less. URL: http://uchoose.info/natsionalni-menshyny-zakarpattya-bilshomu-bilshe-menshomu-menshe/

[23] Preschool educational institutions in 2016 / Statistical Bulletin [Electronic resource]. URL: http://www.cv.ukrstat.gov.ua/publiy/2016/osvita/bul/bul_DNZ.pdf

[24] The third periodic report of Ukraine on the implementation of The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML). URL: https://rm.coe.int/16806f0f09

[25] Preschool education institutions in Chernivtsi region at the end of 2018. State Statistics Service of Ukraine [response to the request]

[26] There are 69 Romanian-language schools in Ukraine. URL: https://tva.ua/2019/04/10/v-ukraini-pratsiuie-69-shkil-z-rumunskoiu-movoiu-navchannia/

[27] Number of schools and students by languages of instruction. URL: https://uiamp.org.ua/uk/isl/dynamika-kilkosti-shkil-ta-uchniv-za-movamy-navchannya

[28] The third periodic report of Ukraine on the implementation of The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML). URL: https://rm.coe.int/16806f0f09

[29] They do not understand: Ukrainian Hungarians and Romanians in the schools practically do not study the state language.

URL: https://texty.org.ua/articles/82794/they_do_not_understand_ukrainian_hungarians_and-82794/

[30] Romanian and Moldovan national minorities in Ukraine: status, trends and opportunities for cooperation: a collection of scientific and expert materials (2019) [Ed. Y. Tishchenko]. Kyiv: NISS. p. 19.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid., p. 26–27.

[33] Romanian and Moldovan national minorities in Ukraine: status, trends and opportunities for cooperation: a collection of scientific and expert materials (2019) [Ed. Y. Tishchenko]. Kyiv: NISS. p. 16.

[34] Ibid.

* This presentation was delivered at a workshop titled “New Law of Ukraine ‘On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language’ (16 June 2019): Ukrainian and Minority Languages,” held at the Justus Liebig University Giessen (Germany) on January 20, 2020.