Should the US Support Ukraine? A Debate in Washington, DC, and Elsewhere

On 30 May 2021, Cato Institute’s Ted Galen Carpenter, on the pages of The National Interest, published an article under the title “Ukraine’s Accelerating Slide into Authoritarianism.” In his outspoken statement, the author painted a dark picture of Ukrainian politics allegedly beset by deeply anti-democratic and ultra-nationalist tendencies. These putative features, Carpenter argued, makes this post-Soviet state unfit for US support. Why the Cato Institute’s fellow – who seems to have neither much interest for, nor ever published any research on, Ukraine – came out with a categorical judgement on this country remains a mystery.

Carpenter’s assessment of Ukraine’s recent history and call for an end to Washington’s backing for Kyiv triggered reactions within the US and outside. The first came from Moscow although Russia was only mentioned en passant in Carpenter’s text. One day after the text had appeared in the United States, the influential Russian state-owned online resource inoSMI (Foreign Mass Media) published a Russian translation of Carpenter’s article, on 31 May 2021. The inoSMI editor introduced Carpenter’s article: “U.S. officials love to portray Ukraine as ‘a courageous democracy that reflects the threat of aggression from an authoritarian Russia’. But the idealized picture created by Washington has never really matched the darker reality, and the gap between the two, with Ukraine sliding increasingly toward authoritarianism, has now become a real chasm, the article notes.”

During June 2021, an interactive debate regarding Carpenter’s attack on Ukraine developed. On the pages of the The National Interest, a response to Carpenter’s initial article was published by Doug Klain of the Atlantic Council. Somewhat later, I published a second rebuttal to Carpenter with the Atlantic Council’s Ukraine Alert. In Ukraine, this text was translated into Russian as well as Ukrainian and republished by the Kyiv website Gazeta.ua. Further responses to Carpenter appeared on the Kyiv resource Khvylia (Wave) in Russian language, and on Berlin’s Center for Liberal Modernity website Ukraine verstehen (Understanding Ukraine) in German language. On 28 June 2021, Carpenter responded to Klain’s and my critique of his initial text with a second article titled “Why Ukraine Is a Dangerous and Unworthy Ally,” again published in the web version of The National Interest, and subsequently reposted on the Cato Institute’s website.

While none of the responses to Carpenter was re-published in Russia, his rebuttal to them was again, within one day, translated by the Kremlin-controlled inoSMI (Foreign Mass Media) website. Carpenter’s new article was reposted in Russian, on 29 June 2021, and introduced by an inoSMI editor: “In May [2021], an author of The National Interest took the liberty of criticizing the Zelensky regime for its authoritarian tendencies. In response, the German ‘Ukrainianist’ Andreas Umland and similar ‘Maidanists’ [a term referring to Kyiv’s Independence Square] criticized Carpenter so much that he decided to get even with them in this article. One cannot remain silent: accusations of ‘Russian disinformation’ are reminiscent of McCarthyism. The defenders of the Kyiv regime have a powerful lobbying organization behind them, the Atlantic Council.”

Also on 29 June 2021, a number of Russian-language outlets published sympathetic reviews of Carpenter’s article, for instance, the major daily Izvestiia (Messages) as well as popular internet resources Lenta.ru and Gazeta.ru. Among other Kremlin-controlled outlets, the website of the Crimean TV channel Pervyi sevastopol’skii (“Sevastopol’s First”) not only briefly reviewed Carpenter’s June article. It had already earlier introduced his May 2021 initial attack on Ukraine, in The National Interest. Among other Russian-language video resources, the Youtube channels “Oleg Kalugin” and “Kognitive Dissonanz” published Russian audio reviews of Carpenter under the titles “On Ukraine’s Lobbyists in the US” (29 June 2021), and “Senior Research Fellow of the Cato Institute […] Ted Carpenter on Ukraine…” (1 July 2021). Carpenter’s two TNI articles on Ukraine were introduced by numerous Russian outlets including Yandex.ru, RIA.ru, MK.ru, Sputniknews.ru, Regnum.ru, News.ru, Tsargrad.TV, KP.ru, PolitRos.com, Life.ru, Argumenti.ru, Actualcomment.ru, RUnews24.ru, PolitExpert.net, Versia.ru, Ridus.ru, 360TV.ru, Riasev.com, Inforeactor.ru, Glas.ru, Riafan.ru, Newinform.com, SMI2.ru, Iarex.ru, TopCor.ru, InfoRuss.info, Profinews.ru, Rusevik.ru, Alternatio.org, News2.ru, News22.ru, and others.

In English, the debate around Ukraine was, on 28 June 2021, reviewed by Jon Lerner of the Hudson Institute, in The National Interest. The English versions of the Russian websites TopWar.ru and Oreanda.ru, published brief reviews of Carpenter’s arguments under the titles “Strategically, Ukraine is a ‘trap’ for the United States” and “American Political Scientist Called Ukraine a Dangerous and Unworthy Ally.” Oreanda.ru remarked that, in Ukraine, “a coup in 2014 was carried out with the help of ultra-nationalist and neo-Nazi groups. Carpenter noted that these organizations with their ‘ugly values,’ continue to influence Kiev’s [sic] politics. Supporters of an alliance with Ukraine try not to notice these facts, the article says. The author of the material noted the deplorable situation with human rights and freedoms in this country.”

The Ukrainian news agencies UAzmi.org and UAinfo.org quoted, on 1 July 2021, an ironic comment by the prominent Odesa blogger Oleksandr Kovalenko who had written on 30 June 2021 about Carpenter’s writings for The National Interest: “Interestingly, he used as arguments what we have regularly heard from Russian propagandists since 2014, namely that neo-Nazism is rampant in Ukraine, rights and freedoms of citizens are trampled in Ukraine, there is no freedom of speech in Ukraine, wild monkeys and crocodiles are in Ukraine… In fact, a full set of Kremlin fakes about Ukraine is heard from the mouth of an American expert on the pages of a respected and influential publication in the midst of the international exercise SeaBreeze-2021.” Ukraine’s leading English-language newspaper Kyiv Post, on 2 July 2021, declared Carpenter – with reference to his articles in The National Interest – Ukraine’s “Foe of the Week.”

The varying responses in Russia, the US, Ukraine and elsewhere indicate the problem with Carpenter’s arguments. What raises eyebrows about his statements on Ukraine is less their critical tone. Rather, it is surprising that Carpenter chose to remark certain sensitive political topics that have been also popular in Russia’s state-controlled mass media during the last seven years, if not before. There are good reasons to criticize, for instance, Ukraine’s dysfunctional presidentialism, underdeveloped party-system, or incomplete cooperation with the International Criminal Court (a topic dealt with on the pages of The National Interest). Yet, these are neither prominent themes in Russian propaganda nor are they issues that Carpenter raises. The Kremlin rarely speaks about such problems as they often also apply to Russia. Carpenter, one suspects, does not mention these and similar topics because he does not read Ukrainian. Judging from the contents of his two articles, he may not have even read much of the freely available English-language scholarly literature on post-Euromaidan Ukraine.

Rather, the Cato Institute’s researcher makes far-reaching claims about an alleged prevalence of ultra-nationalism and putative slide to authoritarianism in today Ukraine – claims also pushed daily in Russian state media and by pro-Kremlin public figures for many years. No wonder that Kremlin-guided newspapers, TV channels and websites have eagerly quoted and reviewed Carpenter’s two articles in The National Interest. Here comes a senior American commentator working at a leading Washington think-tank, publishing in one of the most influential US political magazines, and repeating exactly those talking points that the Kremlin has been spreading to justify its thinly veiled hybrid war against Ukraine for seven years now. This not enough, Carpenter uses the Kremlin’s favorite narratives to unapologetically call for an end of US support for Ukraine. What more could Moscow hope for?

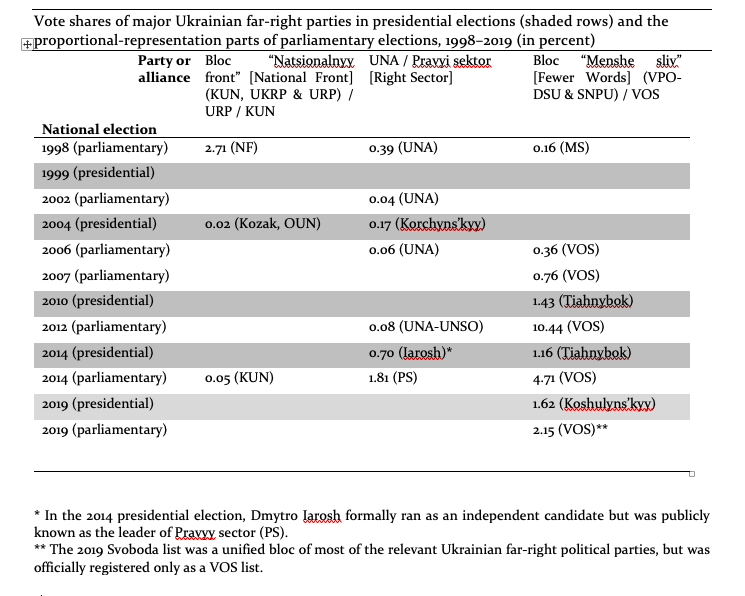

Carpenter’s insistence on the large role of ultra-nationalism in Ukraine is absurd. Unlike various other European parliaments elected via a proportional representation system, the Ukrainian Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Council) does not have a far-right faction any more since late 2014. It had such a faction only for two years from 2012 to 2014. In 2019, Ukraine’s far right – for the first time in its history and unlike many other nationalists around the world – went with a united list into parliamentary elections. Despite such rare harmony, the list of the right-wing Freedom Party which also included representatives of the other two major ultra-nationalist groups, the Right Sector and National Corps, received 2.15% – a result roughly equal to, or even below of, what many single far right parties in European countries receive in national elections. In the 2019 presidential elections, the candidate of the united far right gained 1.62%. Whoever has followed European elections during the last years may note that radical nationalists, in a number of NATO member countries including some older democracies, have received larger or significantly larger support than the Ukrainian united far right.

During its entire post-Soviet history, Ukraine has indeed – as Carpenter indicates – been exceptional in terms of support for ultra-nationalism. However, it has been distinct not for the political strength, but for the electoral weakness of the far right, as the tabled results of various far right presidential candidates and parties, since the introduction of proportional representation in 1998, show. The only period during which the far right was able to gain notable nation-wide support was during the notorious presidency of Viktor Yanukovych in 2010-2014. Yanukovych both triggered nationalist mobilization with his pro-Russian policies and promoted Ukraine’s extreme right, as a convenient sparring partner during elections.

Abbreviations: KUN: Konhres ukrains‘kykh natsionalistiv (Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists); UKRP: Ukrains‘ka konservatyvna respublikans‘ka partiia (Ukrainian Conservative Republican Party); URP: Ukrains‘ka respublikans‘ka partiia (Ukrainian Republican Party); VPO-DSU: Vseukrainske politychne ob‘‘ednannia “Derzhavna samostiynist’ Ukrainy” (All-Ukrainian Political Union “State Independence of Ukraine”); SNPU: Sotsial-natsionalna partiia Ukrainy (Social-National Party of Ukraine); OUN: Orhanizatsiia ukrainskykh natsionalistiv (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists); UNA: Ukrains’ka natsionalna asambleia (Ukrainian National Assembly); UNSO: Ukrains’ka narodna samooborona (Ukrainian National Self-Defense); VOS: Vseukrains’ke ob’’ednannia “Svoboda” (All-Ukrainian Union Svoboda).

There was in 2014, to be sure, something close to panic among many anti-fascists around the world concerning Ukraine’s far right. The Ukrainian ultra-nationalists had still their faction in parliament, been highly visible during the Euromaidan revolution, and entered the first post-Euromaidan government for several months with four ministers. Above all, the Russian propaganda machine and its various Western branches were, on a daily basis, hammering into worldwide public opinion the idea that former President Yanukovych had been thrown out of power by a fascist coup in Kyiv (while, in fact, Yanukovych left Kyiv after violence had already ended, and was officially deposed by the same parliament that had earlier supported him). To be sure, few non-Russian observers bought the Kremlin’s horror story in full. Yet, a widespread approach among Western politicians and commentators has since been that there can be no smoke without fire, and, if Russia is so concerned, the Ukrainian ultra-nationalists must be a relevant problem.

The few academic experts who had researched Ukraine’s far right before it became a popular theme, and studied it from a cross-cultural perspective warned, however, already in 2014 that the media hype around this topic was misplaced. The Russian historian Viacheslav Likhachev (Zmina Human Rights Center, Kyiv), Ukrainian political scientist Anton Shekhovtsov (Center for Democratic Integrity, Vienna) and American sociologist Alina Polyakova (Center for European Policy Analysis, Washington, DC) had researched pre-Euromaidan and non-Ukrainian permutations of the far right before 2014. From their historical and comparative points of view, they and others warned early on that alarmism is inapt and spoke out against an emerging mainstream Western opinion that ultra-nationalism is a major issue in Ukraine.

Some of these researchers explicitly predicted in 2014 that the prospects of Ukraine’s far right are limited. And, indeed, it has since turned out to be again only a tertiary national political force, as it had been before its only notable electoral success (10.44%) of 2012. Today, the overall domestic political impact of Ukrainian right-wing extremists is lower than in many far richer and securer countries of Europe. Even the highly publicized participation of many radical nationalists in Ukraine’s defense against Russia’s hybrid war since 2014 has not had much effect on their electoral fortunes. In 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky with his openly Jewish family background won, against a powerful incumbent, in Ukraine’s presidential elections with a result of 73%.

This leads to the second main point in Carpenter’s two unfortunate portrayals of Ukraine – allegedly authoritarian tendencies disqualifying Ukraine to receive US support. Here again, Carpenter’s argument is bizarre. Ukraine has indeed been exceptional, within the post-Soviet context, yet in the opposite sense in which it has been presented in The National Interest.

Already early in its post-Soviet history, Ukraine passed, after its emergence as an independent state in 1991, one of the crucial tests that political scientists use to determine the democratic potential of a nation: Is an electorate able to kick out a country’s top official and most powerful politician via popular vote? In 1994, the Ukrainians deposed their incumbent regent in a presidential election. As a result Ukraine’s first President Leonid Kravchuk (1991-1994) was replaced by its second head of state, Leonid Kuchma (1994-2005).

The much older and richer Federal Republic of Germany, founded in 1949, passed this particular democracy test only four years after Ukraine. In 1998, the Germans, for the first time in history, deposed a sitting Federal Chancellor, the CDU’s Helmut Kohl (1982-1998), via parliamentary elections that were won by the SPD. The Social Democrat’s then leader (and today employee of the Russian state) Gerhard Schroeder became the new head of government until 2005 when he too was deposed via popular vote. (There had, to be sure, in 1969 been the replacement of then incumbent Federal Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger by the SPD’s Willi Brandt. Yet, this was the result of a change of Germany’s governing coalition and not of that year’s parliamentary elections that had been won by Kiesinger’s CDU/CSU.)

In the 2010 and 2019 national elections again, Ukrainian voters kicked out their sitting heads of state with embarrassing results for the two moderately nationalist incumbents. The then respectively highest office holders, the outgoing Presidents Viktor Yushchenko and Petro Poroshenko, manifestly wanted second terms in Ukraine’s highest political office. Yet, the one-term presidents were spectacularly beaten by opposition candidates, and duly stepped down after their crushing defeats.

Over the last thirty years, Ukraine has conducted dozens of highly competitive rounds of presidential, parliamentary, and local elections most of which fulfilled basic democratic standards. This experience is in sharp contrast to almost all other post-Soviet states that had been part of the USSR when it was founded in 1922. What is special about Ukraine, as a successor country of the original Soviet Union, is the opposite of what Carpenter asserts: It is not the relative authoritarianism, but the relative democratism of Ukraine that is remarkable, and that makes this state more worth of all-Western (and not only US) support than other founding republics of the USSR.

Carpenter’s confusion about these issues becomes especially visible in his second TNI article and rebuttal to Klain and me of June 28, 2021. He compares various post-Soviet states and comes to a strange conclusion: “Umland stresses that other countries emerging from the former Soviet Union are noticeably more autocratic than Ukraine, noting that [in a recent Freedom House democracy ranking in which Ukraine had received 60 out of 100 points] Russia received a rating of twenty points and Belarus received eleven points [out of 100 possible ‘Global Freedom Scores’]. He could have added that Kazakhstan was in the same dismal category with twenty-three points. But no one expects the United States to defend such countries militarily or praise them as vibrant democracies. Umland, Klain, and other fans of Kiev [sic] expect Washington to do both.” However, that is exactly the point: If Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan had achieved the same Global Freedom Scores as Ukraine, in the quoted Freedom House table, they should be treated like Ukraine. If they were – in Freedom House’s parlance – “partially free” and not “unfree,” the three countries would be worth Western support – including assistance by the US (which, by the way, received 83 points in this ranking).

What is, however, most surprising in Carpenter’s two The National Interest articles is not what he writes about, but the preeminent security issue he is entirely silent about – the narrowly understood national interest of the US in Ukraine’s fate as a former atomic power and today non-nuclear weapons state. As indicated in my first rebuttal to the Cato Institute fellow in June 2021, the US played a major role in the nuclear disarmament of Ukraine in the early 1990s. Together with Moscow, Washington pressured Kyiv then to give up not only a major part of the huge arsenal of weapons of mass destruction that Ukraine had inherited from the USSR when achieving independence in 1991. Russia and United States made sure that Ukraine would be deprived of all of its strategic and tactical nuclear war heads and ammunition. Today, Moscow’s and Washington’s concerted efforts from a quarter of a century ago look like direct preparations of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and start of a covert war in Eastern Ukraine in 2014.

The only relevant political concession that Washington made back in the Nineties to Kyiv was that it agreed to supplement Ukraine’s accession to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) as non-nuclear-weapons state with the – now infamous – 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances signed by Ukraine, Russia, the United States and United Kingdom. The latter country also underwrote this fateful document although Great Britain had not taken part in the trilateral negotiations about Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament with the US and Russia. London supported this deal, however, with its official signature because the UK had, in 1968, been one of the – together with US and USSR – three founding countries of the world-wide non-proliferation regime and has since been a depositary state of the NPT. At a CSCE summit at Budapest in December 1994, Washington, Moscow and London assured Kyiv, in connection with its signing of the NPT, of their respect of Ukrainian sovereignty, integrity and borders.

With its attack on Ukraine since 2014 and especially with its overt annexation of Crimea (as well as also with some earlier and other actions), Moscow has been now for several years undermining the logic of the non-proliferation regime. It is not any longer clear that countries which refrain from possessing, building or acquiring nuclear weapons would be secure and especially be protected from countries that do hold atomic arms. Russia’s officially allowed possession of nuclear weapons, moreover, not only gave it a key military advantage vis-à-vis Ukraine. It was also the major reason why the West – unlike in Yugoslavia, Iraq or Libya – has not militarily intervened in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

A widely discussed June 2021 incident with a British war ship near the port of Sevastopol in the Black Sea had thus a more than symbolic meaning. The UK’s destroyer “HMS Defender” passed, on a trip from Odesa to Batumi, by Crimea without making a detour to avoid Black Sea waters claimed by Russia. This behavior of Great Britain was a peculiar form of validation of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum and 1968 NPT. Having received Kyiv’s permission to pass Ukrainian waters, the “Defender” defended not only general international law by taking the shortest path from the shores of Southern mainland Ukraine to its destination at Georgia’s Black Sea coast. The British vessel also upheld the logic of the non-proliferation regime built on the premise that the borders of non-nuclear weapons states are as respected as those of the official nuclear-weapons states under the NPT.

With his explicit demand to end US support for Ukraine, Carpenter calls not only for a betrayal of a beacon of democracy in the post-Soviet space. He also proposes to sweep under the carpet the normative and psychological foundations of humanity’s non-proliferation regime. If – after Russia as the legal successor of the USSR – a second founding country of the 1968 NPT would signal to the world that Ukraine’s territorial integrity and political sovereignty are of secondary importance, this could have far-reaching consequences for the international order. This is especially so as Kyiv once possessed an atomic arsenal that was significantly larger than those of Great Britain, France, and China taken together.

The Kremlin’s manifest violation of the logic of the non-proliferation regime since 2014 can be seen as a temporary and singular aberration of one guarantor of the NPT from a key international norm. An, as Carpenter proposes, US withdrawal from support of the Ukrainian state would, however, create a pattern in the behavior of the non-proliferation regime’s founders. It could signal to political leaders around the world that international law in general and the NPT in particular provide no protection for non-nuclear weapons states. Reliable national security can only be achieved through the production or acquisition of weapons of mass destruction. As the ultimate instruments of deterrence, nuclear war heads may, moreover, come in handily, if a government decides – like the Kremlin did in 2014 – to annex to its state a neighboring territory, and wants to scare away third parties from getting involved.

That Carpenter does not even mention these issues in his two articles in The National Interest is – even more than other aspects of his argument – odd. In so far as Carpenter presents himself, in his articles, as concerned about core national interests of the US, one would think that preventing nuclear proliferation is on his agenda. Yet, Carpenter did not even take an interest in this topic after it was explicitly mentioned in the first rebuttals to his initial May 2021 article.

In fact, the discussion about the grave repercussions of Moscow’s violation of the 1994 Budapest nuclear deal and the resulting implications for US foreign policy has been ongoing for more than seven years now. The debate has been taking place not the least on the websites of various DC institutions – from the Wilson Center for International Scholars to the oldest US journal of its kind, World Affairs (founded in 1837). One would have thought that the Cato Institute’s fellow had taken notice of, and addressed in his deliberations, the gist of the numerous US publications on this topic.

Andreas Umland is Research Fellow at the Stockholm Center for Eastern European Studies at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs, Senior Expert at the Ukrainian Institute for the Future, Associate Professor of Political Science at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, and General Editor of the book series “Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society” as well as Collector of the book series “Ukrainian Voices” both published by ibidem Press in Stuttgart.