Ukraine’s local elections without local political journalism: Results of mass media monitoring reforms

Local journalism is in crisis almost everywhere, what with plummeting revenues, declining professional cadres, challenges presented by new technologies, and advertising migrating towards social networks. However, the Covid-19 pandemic has shown us the dangers of weak local journalism, when the lack of information prevents disoriented audiences from understanding the scale of the threat—for instance, to the quality of medical services in their region. And furthermore, journalism is failing to provide an effective evaluation or analysis of the actions of local authorities concerning how they are dealing with the pandemic, allocating taxpayer funds, etc. This is definitely true for Ukraine, where recent local elections and the pandemic have brought the weaknesses of the local press to the fore.

To obtain a comprehensive picture of the weak and strong sides of the local mass media in Ukraine—which recently underwent mandatory reforms—let us analyze its coverage of the 2020 local elections. We shall use data from the Pylyp Orlyk Institute for Democracy, which has been observing the situation in this sector of journalism. Since the reforms were implemented, by law local authorities cannot be owners or co-owners of the local press (like it was previously, extending back to the times of the USSR). Our study considered the local mass media in eight oblasts (Lviv and Chernivtsi in the west, Sumy and Zhytomyr in the north, Kharkiv and Donetsk (Ukraine-controlled territories) in the east, and Dnipro and Odesa in the south. In addition, four newspapers and their Internet editions (if any) were analyzed.

Why local political journalism in Ukraine is in such trouble

As a rule, all the Ukrainian media organizations that provide election coverage widely practice “jeansa” tactics (covert political advertisement or texts that favour a politician or an official), place political “advertorials” (unclearly marked advertisement), etc. The experts of the Pylyp Orlyk Institute for Democracy additionally analyzed news sources, genres and topics.

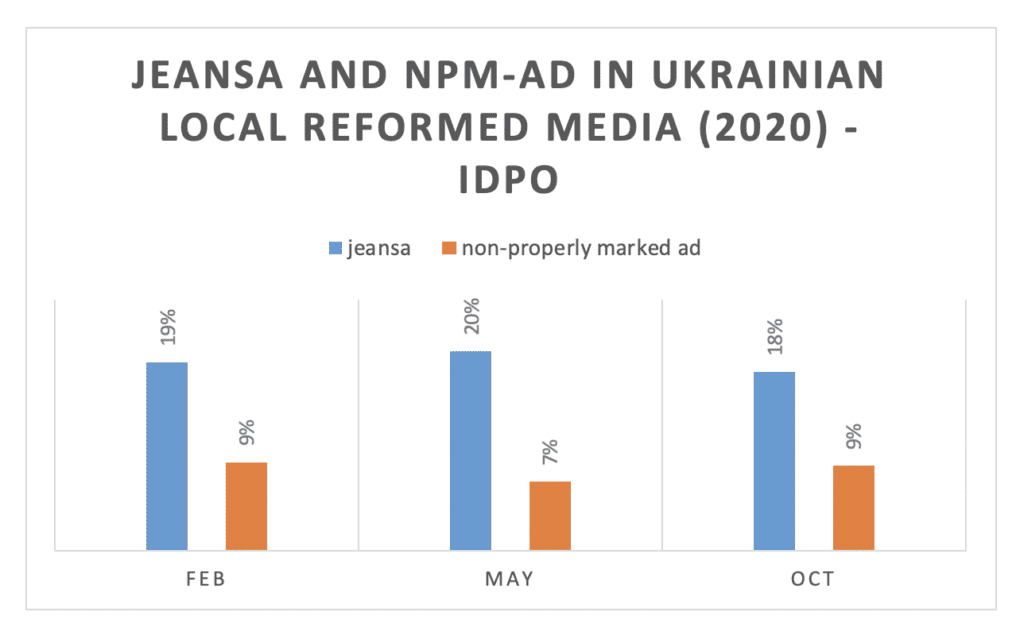

In October during the pre-election campaign, 17.8% of the journalistic texts had some signs of jeansa; the majority of these texts (59%) favoured incumbent local officials, while the rest promoted other candidates for mayors, heads of united territorial communities, political parties or deputies of local councils. The jeansa numbers had been stable during the whole year, e.g., 18.8% in February and 19.9% in May. This observation just confirms previous findings that as a rule, the majority of the reformed Ukrainian mass media still depended on its former owners (local officials of different levels), and the number of “loyal” journalistic materials was stable across various issues. In May the local mass media covered “effective” anti-pandemic measures, and in October it reported on “successful” activities of mayors, local deputies, etc.

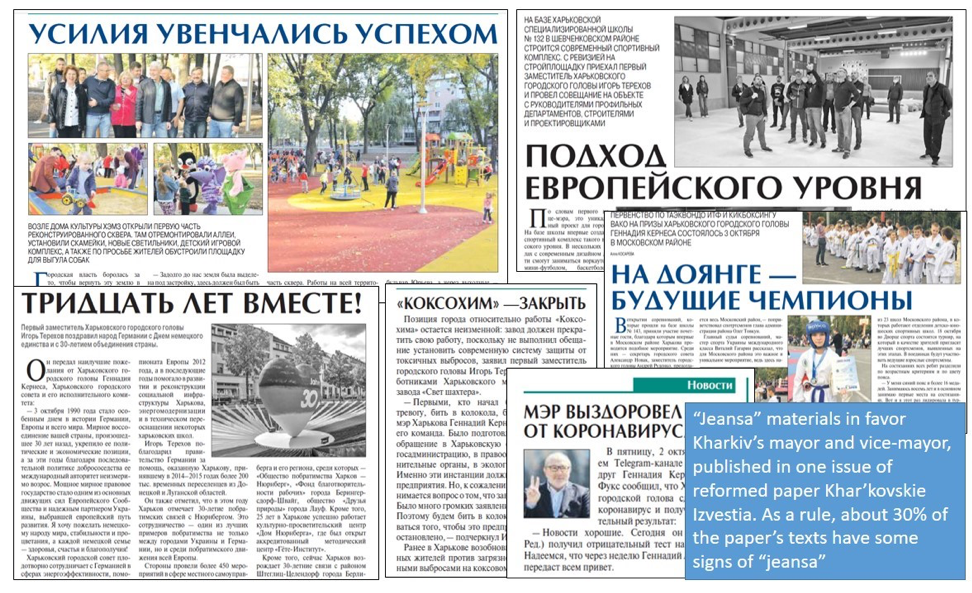

Of more concern was the publication by some mass media outlets of materials favouring only one candidate. For instance, in Kharkiv the local newspaper promoted only the mayor and his loyal officials on the local council. In the surveyed issues of this paper, every third item has signs of jeansa. Furthermore, when in October the mayor Hennady Kernes—formerly a member of Yanukovych’s party—got COVID-19 and left for treatment in a German clinic, the paper promoted deputy mayor Igor Terekhov with the same techniques (Fig. 1). Thus, readers had only one-sided coverage about Kharkiv being an ideal place to live in under the rule of Kernes and his mates.

Figure 1. Examples of jeansa in Kharkiv’s post-reforms newspaper.

The same examples can be found in post-reforms media in Chernivtsi oblast (Chernivtsi newspaper), Dnipro (Kryvyi Rih municipal paper Chervonyi hirnyk ‘Red miner’), and other oblasts.

There are not many newspapers that have successfully implemented editorial independence models, among them Khotyns’ki visti in Chernivtsi oblast, Visti Biliavky in Odesa oblast, and Lesyn krai in Zhytomyr oblast. They give us hope that others will use their experience some time in the future.

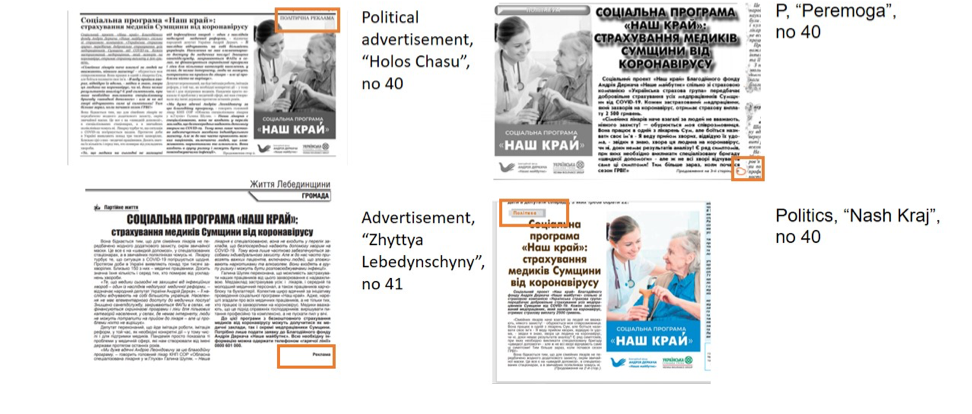

The situation with “non-properly marked” advertisement is better, with 8.5% violations. The papers mainly marked political advertisements as “political agitation / advertisement” (with some violations, viz. Fig. 2). However, another problem emerges. According to Ukrainian legislation, 30% of a newspaper’s space may contain the political advertising. But in local Ukrainian oblast papers we have examples of both properly marked political advertisement and jeansa, published on the first eight pages of a 10-page issue (Obrii Iziumshchyny in Kharkiv oblast) or 2–3 pages of socially significant content in a 24-page issue (Vpered in Donetsk oblast). Because the situation with jeansa mainly concerns only professional media organizations, these violations do not have a significant impact on the broader public.

Figure 2. Ways of marking political advertisement in Sumy oblast: four newspapers marked the same advertisement differently.

In these circumstances, it is really extremely hard for journalists to cover political affairs in their region properly. Some of them still experience pressure from their local authorities or other politicians, or they just try to gain some cash during pre-election campaigning that would allow them to sponsor jeansa ads. Meanwhile, others have insufficient courage to control or criticize politicians and officials who flout the rules.

Indirectly we may observe the consequences of the political coverage by representation of other journalistic genre items in the studied issues. There are no journalistic investigations (0% in eight oblasts) and a general lack of analysis (3.7%). Mostly the mass media publish news and reports (40.6%) and entertainment (horoscopes, crosswords, recipes, congratulations) or local announcements (36.4%).

What about the Internet and new media?

The Internet is usually perceived as having the potential to strengthen democracy, with publishing available to practically everyone. However, in Ukraine—as well as in many other countries with weak democratic institutions—this does not really represent a solution to the prevalent problem.

For instance, the reforms required the media to launch Internet versions of their papers, which would reduce some costs for publishing, distribution, etc. Moreover, online media make it possible to attract targeted advertisement. However, only 36% of the reformed Ukrainian mass media had sites at the beginning of 2020. Usually the papers rely on an older audience and don’t look for young ones. Often local editorial offices don’t have enough digital skills or trained staff. Speaking of online mass media, only a few of them have professional design, effective navigation and texts, or are written in Internet style (with hyperlinks, multimedia and possibilities for interactivity).

As a rule, Internet versions of the reformed local mass media merely republish texts from the print issues without change or copy texts from the official sites of police, local councils, courts, etc. (34.7% of the total number of reprints). And almost every fourth item is missing a proper reference to the source. As for the pre-election campaign, again, the local press typically reprinted “jeansa” political ads (12.9%) or quotes from political platforms and candidates’ photos. As for Covid-19 coverage, readers get only the official statistics, without any comments from medical workers, patients, or experts. As a rule, only local authorities are quoted.

However, here we have some positive examples. For one, the ABO Local Media Development Agency should be mentioned. The organization provides local media editorial offices with professionally designed sites and with mentors who teach journalists to write for the Internet and to look for advertisement.

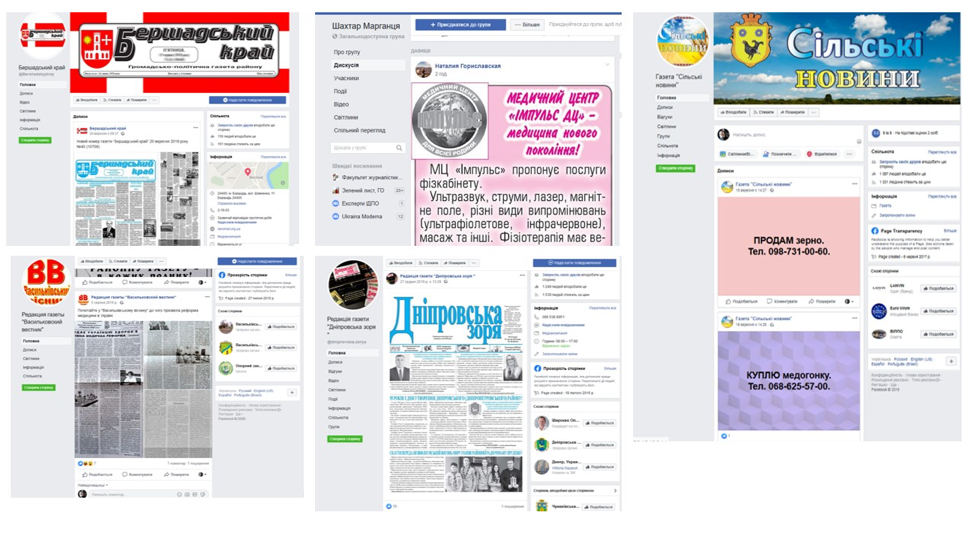

Of course, websites are not the only online option; journalists (both professionals and citizens) may use telegram-channels, Facebook, or Instagram for their purposes. And here more digital skills are needed. The number of post-reform Ukrainian media with FB pages is larger than the number of websites; however, journalists often post only local advertisements, not texts, and reproductions of newspaper pages or local authorities’ press releases (Fig. 3). Even a modicum of training in this field is of significant benefit, because typically the existing local news Telegram-channels and FB communities do not usually rely on traditional journalism practices. According to a study of the Ukrainian Voters Committee and те Еlection Commission, the most popular regional new media publish kompromat and jeansa (anywhere from 3–4% to 100% of items); moreover, there is a lack of news sources in the texts, Russian propaganda is not uncommon, and professional standards are frequently violated.

Figure 3. Facebook pages of post-reforms local Ukrainian newspapers.

In sum, neither the traditional nor the new local media cover political affairs in the Ukrainian oblasts properly. Readers see only political advertisement digests, and in order to make a reasonable decision they must compare political platforms and check campaign promises themselves. However, on the positive side there are some improvements in the marking of political ads and in the development of reformed online media. The credit for the improvements is due to plenty of training and monitoring of Ukrainian journalism. However, more efforts are needed to revive local political journalism for both traditional and new media outlets. This may be the first step forward toward fostering grassroots political engagement and promoting informed local communities.