Law of Ukraine “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language”: The status of Ukrainian and minority languages

Background

The official status of the Ukrainian language is guaranteed by the Constitution of Ukraine. However, the details on the use of the language in different areas of the country should be stipulated in a separate law. Until 2012 it was the Soviet-era Law “On languages in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.” In 2012 the so-called “Kivalov-Kolesnichenko Language Law”—which made it possible to use regional languages instead of the state one—was adopted by Ukraine’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada. A series of oblast and local councils then recognized Russian as their official regional language. In some western oblasts Hungarian, Moldavian, and Romanian also received regional language status.

The Kivalov-Kolesnichenko law further limited the use of Ukrainian, even compared to the Soviet-era law. Language became a much more sensitive issue in Ukraine, where many people speak both Ukrainian and Russian fluently, after Russia annexed Crimea and backed a pro-Russian separatist uprising in eastern Ukraine in 2014. After several attempts to repeal, in February 2018 the Constitutional Court of Ukraine finally declared the Kivalov-Kolesnichenko law unconstitutional. Since then, Ukraine has not had a unified law on state language policy.

Public opinion on the direction that state policy in the language sphere should take was captured in 2017, the year a draft new law was first introduced to the public. Some 61% of survey respondents favoured state support for the Ukrainian language. This support, which had been growing perceptibly throughout Ukraine since 2012, was still outweighed in the more Russian-speaking south and east by concerns over the status of Russian. Though on average the majority (60.1%) preferred a single official language in Ukraine’s future, in the southern and eastern regions almost the same proportions (60.7% and 60.5%, respectively) supported two official languages.[1] As for the citizens, those speaking Ukrainian as well as Russian were most concerned about state protection of their rights. Thus, this law was very much needed, and the country’s best linguists and public figures worked on it.

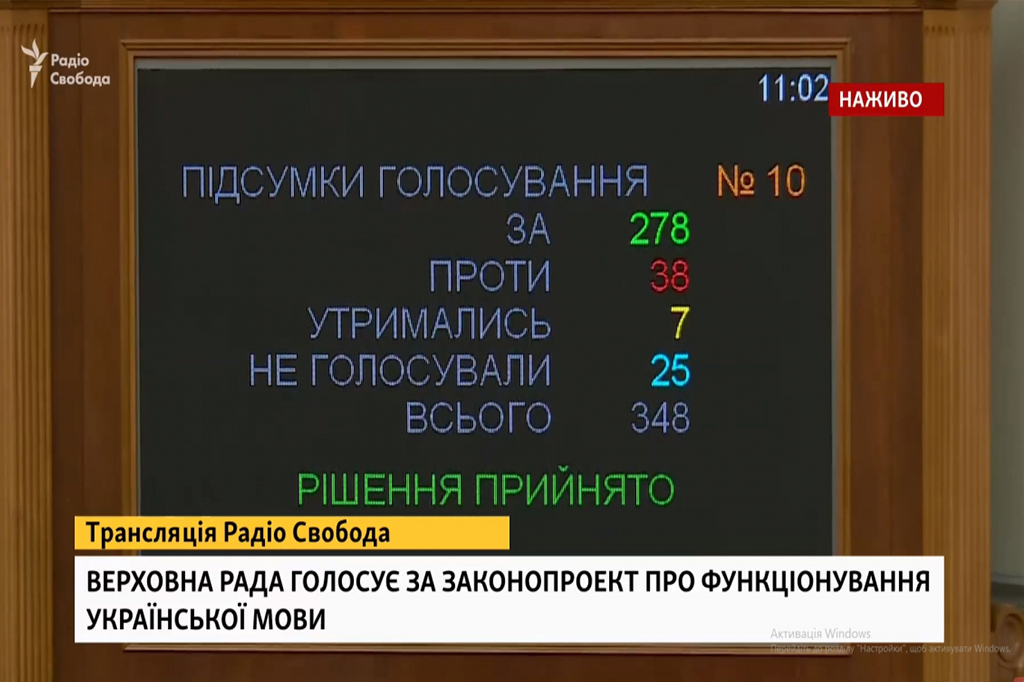

After two readings and the adoption of more than two thousand amendments within the half-year of receiving first reading approval in October 2018, the Law of Ukraine “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language” was passed by the Ukrainian parliament on 25 April 2019. “This is a historic moment, which Ukrainians have been awaiting for centuries, because for centuries Ukrainians have tried to achieve the right to their own language,” said Mykola Knyazhytsky, one of the authors of the bill, before the vote.[2] The official Act on the State Language entered into force on 16 July 2019.

During the presidential election campaign, the candidate Volodymyr Zelensky (incumbent by July) had spoken openly about his skepticism regarding this law and did not exclude the possibility of making amendments to it. Subsequently, a Verkhovna Rada deputy from the “Servants of the People”party, Maksym Buzhanskyi, submitted a draft law (No. 2362) that aimed to repeal the provisions of the Law of Ukraine “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language”—particularly with regard to the conversion of Russian-language schools to Ukrainian as the language of instruction. This initiative caused protests against the Russification of education in Ukraine, and in the end it was announced that Buzhanskyi’s draft bill “On the state language in education” would not be tabled in parliament.

So, what is inside the Law?

The status of Ukrainian as the state language is enshrined in the Constitution of Ukraine. The preamble of the law[3] refers to article 10(2) of the constitution concerning the state’s obligation to ensure “the comprehensive development and functioning of the Ukrainian language in all spheres of public life throughout the entire territory of Ukraine.” The preamble declares the following objectives of the law: “strengthening the state-building and consolidation functions of the Ukrainian language, enhancing its role in ensuring the territorial integrity and national defense of Ukraine,” and “creating proper conditions for protection of the linguistic rights and needs of Ukrainians.”

The law regulates the functioning of Ukrainian as the only state language in the spheres of public life throughout Ukraine. “Ukrainian as the only state language” means that it is also used as the language of inter-ethnic communication, is a safeguard for the protection of human rights for every Ukrainian citizen regardless of their ethnic origin, and is a factor in the unity and national security of Ukraine. The law does not apply to the sphere of private communication and the conduct of religious rites.

As regards the use of languages in education, the law mirrors the provisions in article 7 of the Law of Ukraine “On education”[4] and extends the transition period for their implementation from 1 September 2020 until 1 September 2023—although only for students studying in minority languages that are official languages in the European Union. For students studying in other minority languages, the relevant provisions will take effect earlier, on 1 September 2020.

The law also introduces a new clause that restricts all secondary school finals, “external independent” exams, and post-secondary admissions tests to be only in Ukrainian (except for foreign language tests). This will take effect in 2030.

Setting a general rule on the use of the official language in cultural, art, and entertainment events, the law allows for the use of other languages “if it is justified by the artistic, creative idea of the event organizer” and in other cases provided by the “law on the realization of the rights of indigenous peoples and national minorities of Ukraine.” These language requirements do not apply to singing performances. The law requires ensuring the translation of foreign-language performances in state or community theatres and sets out detailed requirements for movie releases and screenings. The application of these provisions will commence in 2021.[5]

The law allows the publishing of print media in two or more language editions, one of which must be Ukrainian, provided that all the language editions are identical in size, format, and content and are issued simultaneously. Exceptions are made only for media issued in Crimean Tatar or other indigenous languages, and for those issued in English or other official European Union languages (which do not need translation into Ukrainian). The law requires that the Ukrainian-language print media constitute no less than 50% of the selection in all print media distribution points. These rules will apply to national and regional media thirty months after the law is promulgate and to local media in five years.[6]

The law obliges all registered book publishers to ensure that books in the Ukrainian language constitute no less than 50% of their annual publishing output. This requirement does not concern books published in the indigenous or minority languages and funded by the state or local budgets “according to the law on realization of the rights of indigenous peoples and national minorities of Ukraine.”

The law also requires that books in Ukrainian constitute no less than 50% of the selection in all book stores, except for those selling exclusively foreign-language learning materials or books in the official European Union languages, as well as specialized bookstores established for the purposes of “realization of the rights of indigenous peoples and national minorities as provided by law.” These rules will apply two years after the law is promulgated (as of 2021).

The right of national minorities and indigenous peoples to use their languages is guaranteed by this law. The modalities on the use of languages of national minorities and indigenous peoples will be specified by a separate law, in accordance with Ukraine’s obligations under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

The Law of Ukraine “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language” does not rule on the language rights of indigenous peoples and national minorities, although it mentions them sixty-six times.

However, this law does guarantee the rights of national minorities and indigenous peoples to use their languages for preschool and primary education—along with the state language—as well as the right to learn the languages of indigenous or national minorities at general secondary educational institutions or through national cultural societies. The law also stipulates that language courses must be available in the languages of Ukraine’s ethnic minorities.

Reactions to Ukraine’s new language law

Unsurprisingly, Ukraine’s new language law was met with a fierce reaction from the Kremlin, which asked the president of the UN Security Council to convene a meeting over the adoption by Ukraine’s parliament of the law.[7] The Russian mission stated on Twitter:

On July 16, the law “On establishing the functioning of the Ukrainian language as the state language” enters into force. We believe that this law violates Ukraine’s obligations within the Council of Europe. We call on all relevant bodies of the Council of Europe to respond to the violations.[8]

Hungarian institutions emphasized that the Ukrainian language law severely restricts the right of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine to study in their native language. Meanwhile, the Hungarian foreign minister Peter Szijjarto stated that the “Ukrainian language law violates Hungarian minority rights and reflects the vision of President Petro Poroshenko, who promotes anti-Hungarian policies.”[9] István Szávay, vice-president of the far-right Jobbik party, called upon the Hungarian government

to take a firm stance and support the language rights of the Hungarian community in the Lower Carpathians. Our message to the Kyiv government is this: if they find it too much of a burden to respect their citizens with various ethnicities such as Russian, Hungarian, Polish, and Romanian or to ensure their basic humanrights, then let them take the road of independent development.

Moreover, Jobbik, the third-largest party in Hungary, even showed its will to reclaim the Ukrainian territory of Transcarpathia. This ambition is highly unrealistic; nevertheless it could, in theory, lead to additional separatist discourses, which would weaken the country even more.[10]

In the meantime, the Ukrainian government and Ukrainian officials reacted to the statements of their Hungarian and Russian counterparts. For instance, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Pavlo Klimkin (2014–19), pointed out that this law was adopted to support the Ukrainian language, not to prohibit other languages or restrict anyone’s rights.[11]

Conclusions

As of today, it cannot be said that Ukraine has been completely “Ukrainized”; therefore, the Ukrainian language needs protection and development, which is especially addressed by the Law of Ukraine “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language.” In general, this law proclaims that citizens and residents of Ukraine should learn the Ukrainian language. It is challenging to make a career, become a civil servant, or work in the public sector and in the service industry if you do not have a proper knowledge of Ukrainian.

Thus, this article opens up the discussion of how citizens of Ukraine that belong to national minority groups exercise their right to study their native language at preschool and school institutions, through national-cultural associations, in the activities of the publishing sector, as well as in public administration. It provides data and insights that can inform future research into the conditions and status of Russian, Hungarian, and Romanian minorities in Ukraine.

[1] Kulyk, V. 2019. The Law on the functioning of the Ukrainian language in view of citizens’ preferences regarding the state’s language policy. In: Naukovi zapysky 3–4 (99–100). I. F. Kuras Institute of Political and Ethnic Studies. p. 232.

[2] LBTV. 2019. Rada pryiniala zakon pro ukraїns’ku movu ([Verkhovna] Rada adopted law on the Ukrainian language). 25 April 2019. URL: https://lb.ua/news/2019/04/25/425488_rada_prinyala_zakon_ukrainskom.html

[3] Law of Ukraine “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the state language.” URL: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2704-19#Text

[4] Law of Ukraine “On education” no. 2145-VIII dated 5 September 2017. URL: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2145-19

[5] HRMMU (United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine). 2019. Analytical note on the Law “On ensuring the functioning of Ukrainian as the State language” (5 September 2019). URL: http://www.un.org.ua/images/2019.09.11_-_Analytical_Note_-_Language_Law_ENG.pdf

[6] Ibidem.

[7] UN. 2019. Briefing on the situation in Ukraine – Security Council, 8575th meeting (16 July 2019). URL:http://webtv.un.org/watch/briefing-on-the-situation-in-ukraine-security-council-8575th-meeting/6059912457001/?lan=original

[8] TASS. 2019. Russia calls on Council of Europe to react to new Ukrainian language law (16 July 2019). URL: https://tass.com/world/1068773

[9] UAWire. 2019. Hungary: Ukrainian language law is unacceptable (29 April 2019). URL: https://uawire.org/hungary-ukrainian-language-law-is-unacceptable

[10] Chelyadina, I. 2016. Between East and West: The Hungarian minority in Ukraine. Nouvelle Europe, 2 October 2016. URL: http://www.nouvelle-europe.eu/node/1951

[11] UNIAN. 2019. FM Klimkin to discuss Ukraine’s language law with Hungarian counterpart (26 April 2019). URL: https://www.unian.info/politics/10532313-fm-klimkin-to-discuss-ukraine-s-language-law-with-hungarian-counterpart.html