Communicating defeat? Poroshenko’s Twitter before and after the second tour of the Ukrainian presidential election

According to crisis communications principles, a crisis is in the eye of the beholder (audience or stakeholder). Thus, if your audience doesn’t see a crisis, there isn’t one (see Coombs, 2007).[1] However, what if a politician decides to convince his/her voters that there is no crisis?

In the reality of social networks, filter bubbles, and tmi (“too much information,” a common expression currently for being overwhelmed with excessive information assortment, availability, and detail) this technique may be useful. In the internet era, because of deadline pressures, staff reductions, and lack of knowledge and resources, journalists may not seek additional information and use only twitter or facebook as their main sources of information. Finally, audiences are more and more often feeling disappointed with mass media news coverage, while some politicians try to besmirch the mass media as “fake news” and “enemies of the people.”

Twitter in Ukrainian political communication

In Ukraine there are 26 million active internet users (58% of the total Ukrainian population). In addition, almost half of them use “social media” networks (see We are social report 2018). In order to reach this audience, Ukrainian politicians actively post on two of the most popular social media platforms, Facebook and Instagram (see this investigation by Radio Liberty Ukraine for more details).

In contrast to Western countries, Twitter is not as widely used in Ukraine. However, during the Euromaidan the platform was an effective tool to promote Ukraine and its European intentions all over the world (similarly to the Arab Spring). Pro-Ukrainian activists used a variety of Twitter accounts and wrote a numerous posts in English, French, and other languages to resist Russia propaganda and report on events in Kyiv, Donetsk, Kharkiv, and other hot spots of the so-called “Revolution of Dignity.” Since the Euromaidan, Twitter has remained in this position, and today it continues to connect Ukrainian politicians, journalists, and activists with international audiences, predominantly from the EU, the US, and Canada.

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko’s Twitter account emerged in April 2014 (he was elected on 25 May 2014), and his Facebook account was created in July 2014. Poroshenko has 1.21 million readers on Twitter and 2.4 million on Facebook.

Analyzing Poroshenko’s Twitter account may help us to reconstruct the main communications techniques that were used during the difficult periods before and after the second tour of this year’s presidential election.

After Poroshenko was defeated and recognized the victory of his rival, Volodymyr Zelensky, some flash mobs were organized in support of Poroshenko. Over one thousand of his followers came to Bankova Street, where premises of the Administration of the President of Ukraine are located, sang the Ukrainian anthem, and cried out “Thank you!” People also used the hashtags (here transliterated from Cyrillic) #diakuiuporoshenku (thank you to Poroshenko) and #diakuiupanepresident (Thank you, Mister President) in social networks. In addition, some supporters used “diakuiu” stickers on their Facebook avatar photos.

Thus, Poroshenko’s defeat was decisively used as a step toward possible future victories. He was able to mobilize people around his defeat. Of course, “politics of resentment” were in the picture, as is traditional for our digital times (Fukuyama 2018).[2]

Poroshenko’s messaging pointed to Zelensky’s connections with Russians and with the Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky. However, the Russian threats were not the only theme in the activity of Poroshenko’s supporters. The former president used Ukrainian national symbols and traditions, highlighted his achievements, and emphasized international support. For these reasons, it is interesting to study his Twitter account for discoveries in the field of modern political communication.

Method

Between 1 April and 31 June, 552 tweets were collected and analyzed. Structural and narrative analysis were used for the research.

Narrative analysis has been widely used in political communications research since the times of US president Barak Obama; it was Obama’s story that convinced Americans to vote for him. Narratives are also extremely important for modern digital propaganda, where emotional and aggressive stories replace facts and rational arguments.

The main question for narrative analysis is “who is speaking,” and from the result researchers can reconstruct the personality of the narrator and discover transformations made with the narrative.

The logic of structural analysis is to present discrete texts (for instance, poems, news items, or tweets) as one text, and to find the leading topics, phrases, or techniques that are used in order to influence readers. In this process, researchers can construct glossaries used by authors.

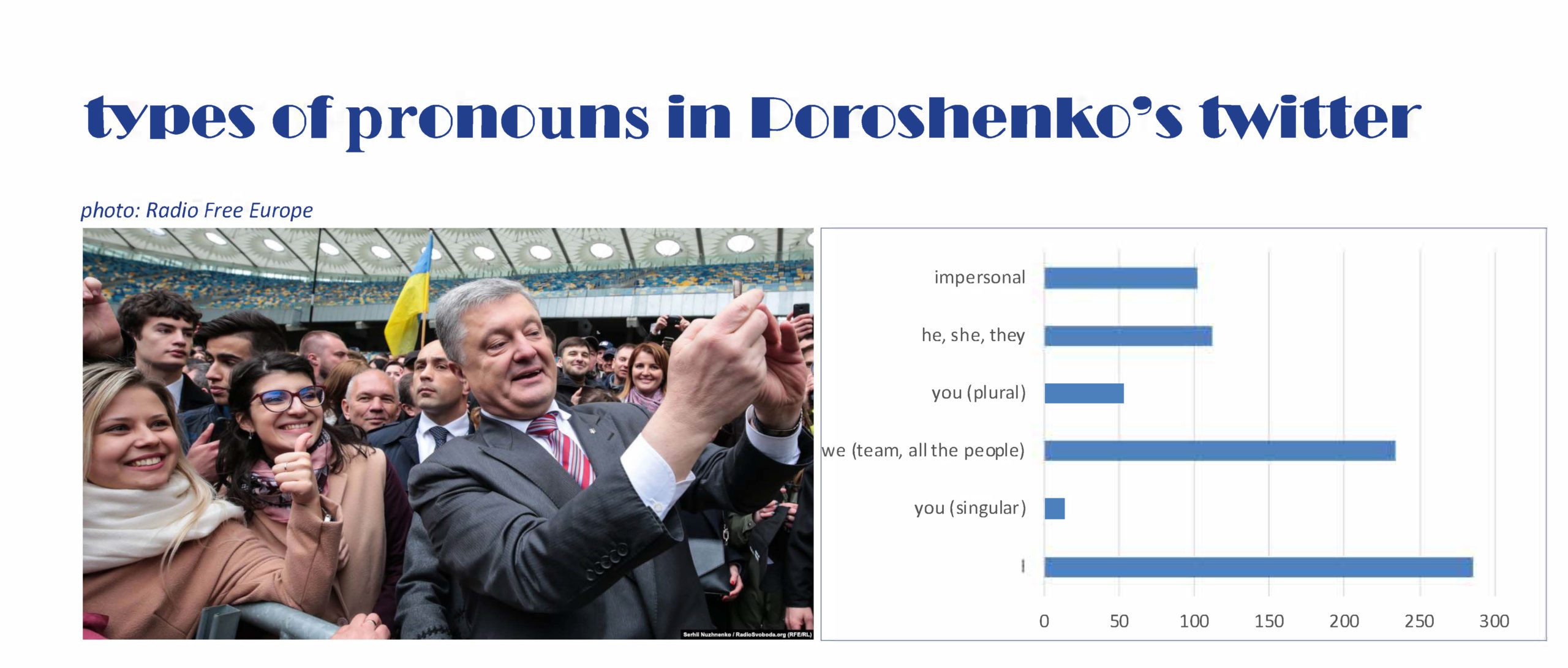

Thus, in this research, first Poroshenko’s tweets were classified into categories: “I-tweets” (with the first person (singular) pronouns), “you-tweets” (the second person singular pronouns), “we-tweets”, “he/she/they” tweets, and impersonal (no pronoun used) tweets. If a tweet contained both first and second person pronouns, it was put in both categories.

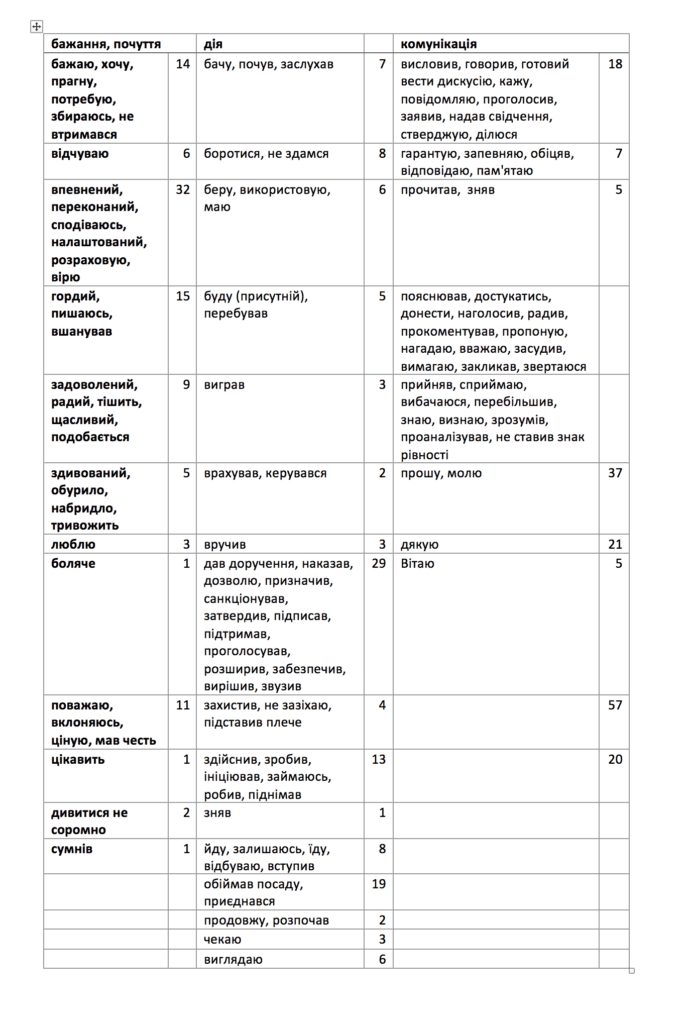

For this study, the “I-tweets” were used to reconstruct the narrator. I concentrated on Poroshenko’s verb usage, because modern politicians are usually accused of “all talk, no action,” and in a president’s activity it is extremely important to communicate actions in a proper way. Let us examine the results of composing the glossary of Poroshenko’s most-used verbs.

“I-tweets” and charisma in Ukrainian politics

Ukrainian politics is about leaders, not ideas or political trends. That is why Ukrainian parties usually do not have a long life. This is explained in part by post-Soviet tradition and by total distrust of politicians and social institutions among Ukrainians. Thus, the language of political communications reflects this.

In Poroshenko’s tweets, the first person pronoun is used more often. However, “we-tweets” are also popular, but the meaning of “we” may be as “my team” and as “all Ukrainians.” With “he/she/they” tweets Poroshenko is usually referring to his opponents. And the impersonal pronouns are also quite frequent, used to answer to accusations against him and his policies. “You-tweets” of both kinds—singular and plural—were rarely encountered.

All this means that Poroshenko hasn’t changed the Ukrainian political style of communication. He is the most significant figure—not his team, the Ukrainian people, the military, or his opponents. And as we are speaking about a politician who lost the election, this may be an interesting case. He is not hiding, but rather is demonstrating that the game is not over.

Feel confidently and speak with gratefulness: A close look at Poroshenko’s “I-tweets”

During the second-round election campaign, Poroshenko admitted on Twitter that his communication with Ukrainians hadn’t been ideal. The fifth Ukrainian president promised to change that, as well as his political team.[3]

However, he did have a justification for the difficulties in communication: “I understand, I didn’t speak a lot with you [all the people]—I was busy with the country.”

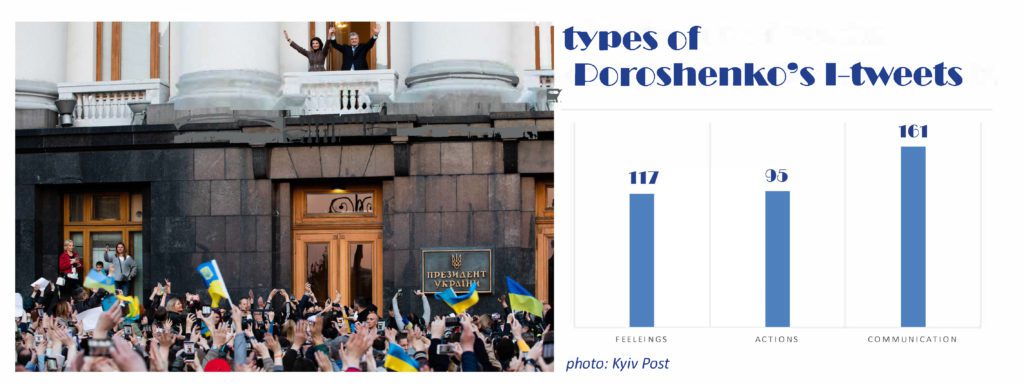

Thus, with his tweets during the election campaign and after it (when the need for changes is normally comprehended), we will be able to trace Poroshenko’s typical communication style. These elections were indeed challenging for Poroshenko; however, his personality, actions, and feelings were extremely important for his future political career. To this end, the “I-tweets” were grouped into three categories: what the former president feels, does, and says.

Thus, Poroshenko uses his Twitter account to highlight his communicative intentions. In fact, Poroshenko’s claim that “I didn’t speak a lot with you” isn’t correct, as both he and his press office were active on social networks and in the mass media. So, this interesting claim might be understood as “I didn’t speak a lot with you” compared to his speaking with others. Moreover, “Ukrainian people” as an addressee of Poroshenko’s tweets (an explicit addressee) doesn’t match up with the actual one.

As for “feelings” and “actions,” the number of occurrences is nearly equal. So emotions are significant in Poroshenko’s political statements—and this seems to be a general political trend in the 21st century (see, for instance, Thompson’s observation about a misbalance between “pathos, ethos, and logos” in political rhetoric; Thompson, 2016).[4]

Poroshenko’s top feelings: Confidence, proudness, and respect

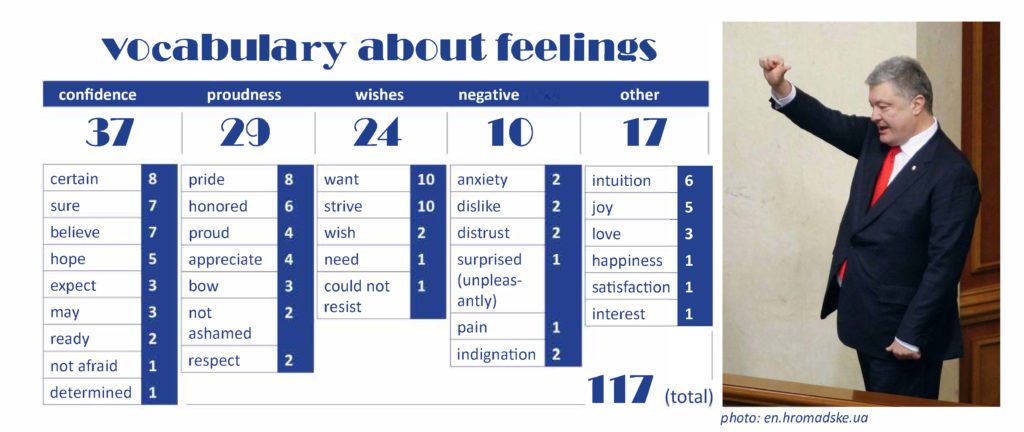

Mostly Ukrainian President Poroshenko speaks about his confidence about something. Such narratives may be understood as powerful ones, where the narrator’s confidence is used to underline his authority and persuade people to feel the same. This also reflects a pre-election tradition wherein all the candidates should communicate their confidence in a future victory. So despite numerous accusations and claims of opponents, Poroshenko demonstrates that the attacks are meaningless, and he feels confident about his presidency and its effectiveness.

The second the most popular vocabulary group confirms this discovery: mentions about pride. This means that the former president speaks about some significant values that were created or recreated during his presidency. And these values are identified with his personality. Additionally, pride and respect reaffirm the confidence factor, as one may respect something only if he or she is confident in the significance of this thing. Poroshenko also repeats several times that he is proud of himself as a president, and stresses that he is not ashamed of anything.

The third group concerns Poroshenko’s wishes. This vocabulary is usually about the former president’s visions about the future, and may be used to confirm his statement about his unfinished tasks in the presidential post, which must be finished in any circumstances (by Poroshenko as the elected president or Poroshenko as the opponent of Zelensky). And, of course, his wishes are not just caprices but the strong needs of a responsible person.

Only 10 words are connected with negative feelings: “indignation,” “anxiety,” “unpleasant surprise,” and “pain.” Poroshenko did use negative criticism (for Zelensky, Putin, and Russia), but the former president was not a sender or a communicator (in Lasswell’s terms). The criticism was made with less concrete pronouns, like “we,” “they,” or impersonal.

Thus, we can say that Poroshenko’s communicated feelings are mostly positive and optimistic. The politician as a narrator doesn’t feel guilty, nor does he promise to correct any mistakes.

Poroshenko as a communicator: “Thank you” and “Congratulations”

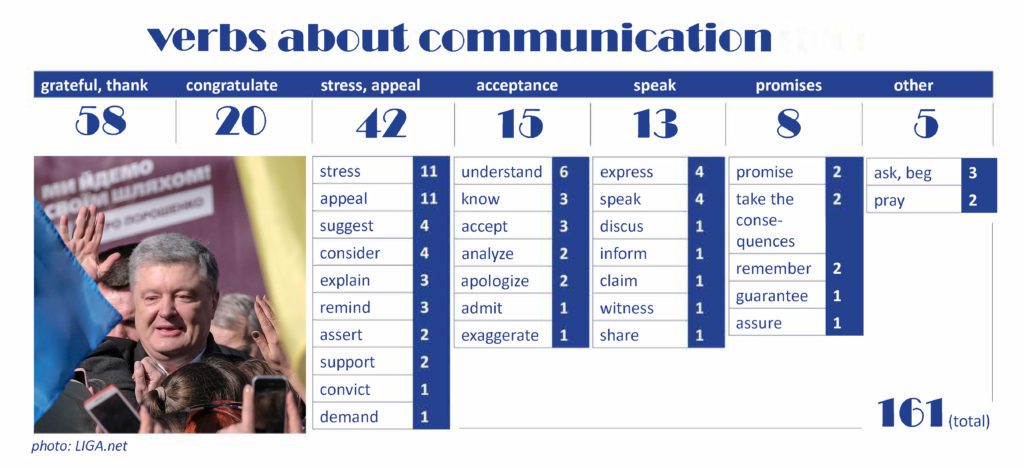

The former president’s Twitter communications are kind of ritual, which are used to show stability and order. Among the verbs concerning his communicative intentions, the most popular is “thank,” with 58 mentions. This correlates with his expression of pride—Poroshenko’s second popular feeling and the second most popular verb—“congratulate” (20 mentions).

Poroshenko tries to set an agenda on his twitter (with some kind of emphasis being the most popular item). However, sometimes he admits to problems, especially in the several days before the election and after. Additionally, it’s interesting to discover that Poroshenko-as-narrator gives preference to dramatic words and frequently uses neutral pronouns to express his communicative intentions. This observation confirms our above-mentioned remark about his communication being a kind of ritual.

Poroshenko’s actions: Orders and meetings

Even after his defeat in the election, Poroshenko continued to speak about his activity as president. In this way he strove to convey his intention to remain in Ukrainian politics. That is why verbs about him signing documents and giving orders are among the most frequent ones.

Conclusions

On his Twitter, the incumbent Ukrainian president, Petro Poroshenko, framed his defeat with a popular expression: “We lost the fight, we’ll win the war.” Actually, he doesn’t speak a lot about it and instead pays attention to significant values and achievements. And the flash mobs of his supporters are a confirmation of the successfulness of his communicative strategies on social media. We note here, however, that this applies to the approximate 25% of Ukrainians who voted for him.

Poroshenko did not try to appeal to Zelensky’s voters by speaking their language. He mentions these voters on his Twitter, and he tried to communicate his messages with a megaphone during the debate in the Olimpiiskyi stadium. But he spoke within his own narrative, where he is a successful, respected, and confident leader.

The politician’s thesaurus was complicated, and we might conclude that he tried to appeal to a specially selected audience, not to everyone. During the debates, the former president additionally distinguished between his and Zelensky’s voters, challenging his opponent’s way of communicating with this appeal: “[A proper form of address is] Not ‘dudes’, but a very respectful ‘ladies and gentlemen’!” Evidently, the “dudes” tactic turned out to be the more convincing one.

And this may be a characteristic feature of president’s speeches.

His strategy of confident narration in some terms confronts the strategies which were used by his opponents during the pre-election presidential campaign (and are being used now, before the parliamentary elections). It could be said that anti-Poroshenko rhetoric was used mostly by all the candidates, and the presidential challenger Zelensky said during the debates, “I am the result of your mistakes and promises.”

Poroshenko denied all the accusations, and in one tweet[5] he stated: “Your were told a lot of terrible lies about me.”

Additionally, if a person feels guilty about something inadequate (in our case, the way of communication), this will be reflected in his or her phrases. Pity, uncertainty, or sadness would be stated in some way, and perhaps some promises made about possible changes.

Poroshenko in his account is not a real personality. It’s just a role, a “mediatized” personality.

[1] Coombs, W.T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory, Corporate Reputation Review 10(3):163–77.

[2] Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[3] Poroshenko usually gave preference to press conferences with specially selected journalists. In 2016 a Freedom House reported some concern about Poroshenko’s claim that journalists should avoid critical stories about Ukraine.

[4] Thompson, M. (2016). Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong with the Language of Politics? New York: St. Martin’s Press.

[5] Я люблю Україну. За нелегкі роки мого президенства вам розповіли про мене багато жахливої неправди. Якби я міг в неї повірити, я би і сам за себе не проголосував. Але мине час, історія все розставить по свої місцях