Anne Applebaum. Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. (Book Review)

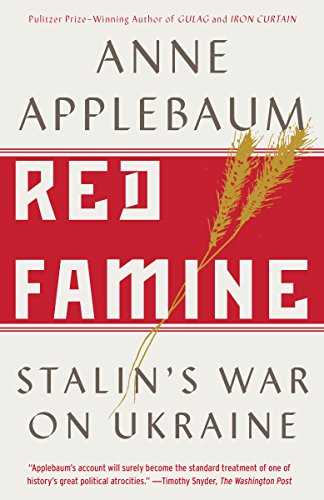

Anne Applebaum. Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. McClelland & Stewart, 2017. xxxii, 464 pp. Illustrations. Maps. Notes. Selected Bibliography. Index. $42.00, cloth.

Anne Applebaum sets out to tell the story of the Ukrainian famine of 1932-33, and she does so masterfully and powerfully, providing the historical background, the political and economic context, and a blow-by-blow account of the decisions that led to the annihilation of at least four million Ukrainian peasants. It is, frankly, depressing reading, despite Applebaum’s valiant effort in her final pages to mitigate the horror by invoking Ukraine’s independence and freedom today. The Bolsheviks viewed Ukraine as little more than a granary and its inhabitants as expendable non-proletarians whose only function consisted of providing Russia’s hungry proletariat with food. This was colonialism, pure and simple. And it is important for scholars to state, unconditionally, that it was evil.

It was also totalitarianism, at least by the late 1920s and 1930s, when Stalin and his Bolshevik henchmen constructed a system that incorporated all human activity and subordinated it to their murderous ends. There was slippage and there was chaos, of course, but the overriding reality was that there was top-down control by means of a ramified set of relationships that compelled everyone to play a preassigned social, political, economic, or cultural role. Some resisted and were shot. Others evinced insufficient enthusiasm and were purged. The system of incentives was such that collaboration was the only rational response for someone concerned above all with survival—a lesson that few Ukrainians would forget in subsequent years.

Although Applebaum’s book contains no surprises for students of the Holodomor, her straightforward account of the consistently anti-Ukrainian rhetoric and behaviour of Russia’s Bolsheviks, from before the Revolution, through the famine, and for many decades thereafter, demonstrates that the Communist “project” in Ukraine was, above all, exterminationist. Whether properly called a genocide or just an unimaginably huge mass murder, the Holodomor, along with the destruction of Ukrainian religious, artistic, intellectual, and political elites, was the deliberate culmination of Bolshevik policies in Ukraine and not the accidental by-product of overzealous collectivization and bad decision-making, as revisionist scholars insisted for so long. Indeed, the famine provides the most compelling piece of evidence for viewing Soviet socialism as a morally bankrupt system and its apologists, then and now, in Russia and in the West, as morally responsible for four million deaths. 228 East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies

Applebaum shows that the Holodomor was not only Stalin’s doing. His henchmen were as implicated as he was. The secret police enthusiastically carried out his murderous instructions, and a whole range of officials, activists, and collaborators (many of whom were simple peasants who chose to kill in order to avoid being starved) took part in depriving the Ukrainian peasantry of all of its food. Applebaum does well to emphasize the role of peasant collaborators. But her focus on high-level decisions and low-level implementation overlooks the key role of the secret police, whom she mentions only cursorily as having collected information and executed prisoners. But the secret police formed the indispensable middle link between the authorities and the perpetrators. Who were these thousands of OGPU and NKVD murderers? How, exactly, did they participate in implementing the famine? Could the famine have taken place without them? My guess is that the answer to the last question is no. Future researchers would do well to follow the example of students of Nazi atrocities and devote their research to the legions of “chekists” who made Soviet totalitarianism work.

Applebaum’s work, like George O. Liber’s excellent book Total Wars and the Making of Modern Ukraine, 1914-1954 and Timothy Snyder’s book Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin, demonstrates that Ukraine experienced unmitigated death and destruction for a good portion of the twentieth century. Ukraine’s population suffered some fifteen million excess deaths in the period between 1914 and 1948. That is an average of 441,000 a year for thirty-four years. The Holodomor, which took at least four million lives in about six months, evinced an astonishing annual kill rate of eight million. Even the Holocaust falls short, with an annual kill rate of about 1.25 million. If such a record does not merit being labelled as “The Black Deeds of the Kremlin” (the name of an early two-volume history of the famine that was lambasted by Western scholars as overly emotional and Cold War-ish), then nothing does. Revisionists may not know it—and judging by Sheila Fitzpatrick’s criticism of Applebaum, some of them do not—but revisionism as an intellectual project is dead. Applebaum’s work may be the last nail in its coffin.

Applebaum’s account will set the norm for Holodomor studies for many years to come. Her research is impeccable, and her sources are comprehensive (except for one minor detail: oddly, she appears not to have been aware of the work The Holodomor Reader: A Sourcebook on the Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine, which Bohdan Klid and I co-edited). The most important thing, perhaps, is that the writing is superb. Applebaum avoids jargon and knows how to tell a dramatic story with fine prose and admirable restraint. She also understands that the way to make a Ukrainian story interesting for a broader readership is to tell that story well.

Alexander J. Motyl

Rutgers University-Newark

Works Cited

Fitzpatrick, Sheila. “Did Stalin Deliberately Let Ukraine Starve?” Review of Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, by Anne Applebaum, The Guardian, 25 Aug. 2017, 7:29 BST, www.theguardian.com/books/2017/aug/25/red-famine-stalins-war-on-ukraine-anne-applebaum-review. Accessed 27 Aug. 2018.

Klid, Bohdan, and Alexander J. Motyl, compilers and editors. The Holodomor Reader: A Sourcebook on the Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. CIUS P, 2012.

Liber, George O. Total Wars and the Making of Modern Ukraine, 1914-1954. U of Toronto P, 2016.

Pidhainy, Semen O., editor-in-chief. Book of Testimonies. Translated by Alexander Oreletsky and Olga Prychodko, introduction by George W. Simpson, Ukrainian Association of Victims of Russian Communist Terror, 1953. The Black Deeds of the Kremlin: A White Book, vol. 1, 1953-55. 2 vols.

—, editor-in-chief. The Great Famine in Ukraine in 1932-1933. Introduction by Charles J. Kersten, F. U. P. The World Federation of Ukrainian Former Political Prisoners and Victims of the Soviet Regime, 1955. The Black Deeds of the Kremlin: A White Book, vol. 2, 1953-55. 2 vols.

Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books, 2010.

Republished from: (2018 East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies (ewjus.com) ISSN 2292-7956 Volume V, No. 2 (2018) DOI:https://www.ewjus.com/index.php/ewjus/issue/view/14/showToc )

![Review of Andreas Kappeler. Ungleiche Brüder: Russen und Ukrainer vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. [Unequal Brothers: Russians and Ukrainians from the Middle Ages to the Present].](https://ukrainian-studies.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/9_47_kappler_ungleiche_brueder_shop.jpg)