Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: The first day of the war in Russian TV talk shows

On 21 February 2022 the Russian Federation officially recognized the “sovereignty” of two occupied territories around Donetsk and Luhansk cities in the Donbas region of Ukraine. Only three days later, in the morning of 24 February Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, which the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, announced as a “special military operation” to “demilitarize and denazify” Ukraine. Since the very beginning of this war, the media have played a crucial role because they significantly influence the way the public perceives the events in Ukraine. In the Russian Federation, the state-owned media form the “mouthpiece” of the current regime and are one of the most important means to justify the aggression and violence in Ukraine officially. This article examines how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was legitimized on Russian state television by concentrating on one of its core formats—the TV talk show.

Television in Russia

Although the number of Internet users is increasingly growing in Russia, public TV remains the most effective nationwide means of mass communication. According to opinion polls, more than 60 percent of Russia’s population relies on TV as a source of political information. About 46 percent of the viewers trust and believe the information they receive via television. On the other hand, as most Russian TV channels are funded or co-funded by the Russian government, they broadcast exclusively official, one-sided, and highly biased information.

Until February 2022 there were only a few non-governmental TV channels left, including for instance the channel Dozhd’ (TV Rain)—which, however, could only be received via the Internet and was declared a “foreign agent” by the Russian government in 2021. As a result of the war in Ukraine and the increased pressure on and threats against non-governmental media in the Russian Federation, Dozhd’ had to stop broadcasting in March 2022.

Today, only three TV channels in Russia are significant in terms of their nationwide reach of more than 75 percent. These powerful channels are Pervyi kanal (Channel One), Rossiia-1, and NTV.

The TV talk show – A popular format

One of the most popular formats on Russian television is the talk show. For example, Pervyi kanal broadcasts approximately 10 hours of talk shows every weekday, which are only interrupted by news shows (Novosti and Vremia). Figure 1 shows Pervyi kanal’s program on 24 and 25 February 2022:

This small extract of Pervyi kanal’s weekly program illustrates a phenomenon that Anna Kachkaeva, a media scientist at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, already noticed in 2015. Her observation is that talk shows and news broadcasts form a unity between information, entertainment, and emotion: “While policymakers and straight news shows define the agenda, the political talk shows provide ‘emotional support’. […] They just support the atmosphere that exists and heat it up.”

One of the talk shows that interconnects daily with the news broadcasts is Vremia pokazhet (Time Will Tell). Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this program has been producing approximately four to six episodes every weekday, frequently with an overall broadcast time of more than six hours. Vremia pokazhet has existed since September 2014 on Pervyi kanal, and from the beginning it has mainly been concerned with the Russian war in Ukraine. What is particularly interesting is the fact that Vremia pokazhet is a political talk show broadcasted during the day. This is special and unique, because political talk shows usually are part of the evening or night program. For this reason, the prominent Russian television critic Irina Petrovskaia already concluded in 2014 that Vremia pokazhet demonstrates the “absolute know-how” of Pervyi kanal by producing “politics for housewives.”

First day of the war on Vremia pokazhet

Below it will be shown which arguments were produced in the talk show Vremia pokazhet to legitimize the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This analysis focuses on the very first broadcast on 24 February—the day the escalated invasion began. This broadcast lasts one hour and 10 minutes, and it is moderated by two hosts, Artëm Sheinin and Anatolii Kuzichev (see fig. 2). Nine guests participate in the studio; two other guests are connected to the studio via a live video link. All the participants in this episode are male.

(1) “We had no other option”

One of the first and thus one of the most important claims in the show is that the military operation was the only option. This pretended inevitability was first announced by the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, in his speech in the morning of 24 February: “I repeat, we simply could not do otherwise.” Parts of his speech are shown throughout the broadcast, and the two moderators as well as the talk show guests reiterate that there was no other way than starting this military operation. For example, one of the hosts, Anatolii Kuzichev, poses a rhetorical question, which he immediately answers himself:“Were there any options? Of course, there weren’t. No other options.” One of the guests, Vasilii Fatigarov, emphasizes that Russia is a “peace-loving country” (miroliubivaia strana). This statement, however, completely contradicts his subsequent conclusion, in which he agrees with the other guests that there was “no other way” (drugogo puti ne bylo) than to invade Ukraine.

(2) “Russia is bringing peace to Ukraine”

As Russia is called a “peace-loving” country by one of the show’s guests, it is hardly surprising that another legitimization is Russia’s claim to bring peace to Ukraine. According to one of the guests, Vladislav Shurygin, the “special operation” is, in fact, a “peace operation” because Russia is conducting a “peace enforcement” (prinuzhdenie k miru) in Ukraine: “This is called a peace enforcement operation. […] Again, we are conducting the demilitarization of Ukraine, and we are conducting peace enforcement.” This argument, however, is not new because already in 2014 Russia portrayed itself as a peacemaker in Ukraine and Vladimir Putin as its principal initiator. Earlier than that, in 2008 Russia invaded Georgia to “enforce peace.”

(3) “It is not war but liberation”

The third legitimization articulated in the show is that it is not war but “liberation” (osvobozhdenie). There are two different emphases of the portrayal of Russia as a liberator: First, it is argued that Russia is freeing Ukraine. According to the talk show guests, Russia’s war is not a war but the liberation of Ukraine from NATO, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom. For example, Il’ia Kiva, a right-wing and pro-Russian Ukrainian politician, states that Ukraine has been “enslaved” and “occupied” by the United States and the United Kingdom, using Ukraine to provoke Russia. Another guest, Vladimir Sergienko, argues that Russia is not destroying Ukrainian but rather NATO infrastructure, alluding thereby that NATO is already involved in the war.

The second liberation argument concerns only the Donbas region. The assertion that Russia is helping and freeing people from the Donbas region was already made in 2014. In 2022 the self-appointed leaders of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic [1] officially asked Russia for help and requested its military support. In the talk show, this help is justified by Putin’s claim that there has been a genocide of the Russian-speaking population in Donbas for eight years, which Russia is now going to end. In this context, one of the guests, Vladimir Kornilov, makes a paradoxical statement, declaring that “the war is withdrawing from the people in Donbas thanks to Russia’s military operation.” According to him, they now do not have to hide anymore in cellars and can rebuild their houses. Therefore, he concludes, the “special operation” is the same “celebration” (prazdnik) for the people as in 1943, when Soviet liberators came to free Stalino. [2] One of the moderators agrees and adds that today it is a “celebration of freedom” (prazdnik mira).

(4) Self-defense and self-protection

In this first talk show broadcast, a fourth argument to legitimize the war is Russia’s need for self-defense and self-protection. For Vladimir Putin, Russia’s need for self-defense required this “special operation” in Ukraine. The talk show guests support Putin’s claim by accusing the Ukrainian side of not respecting the Minsk Agreements, in particular of breaking the ceasefire. For example, one of the hosts announces at the beginning of the show that the Ukrainian security forces have violated the ceasefire “177 times in the last 24 hours.”

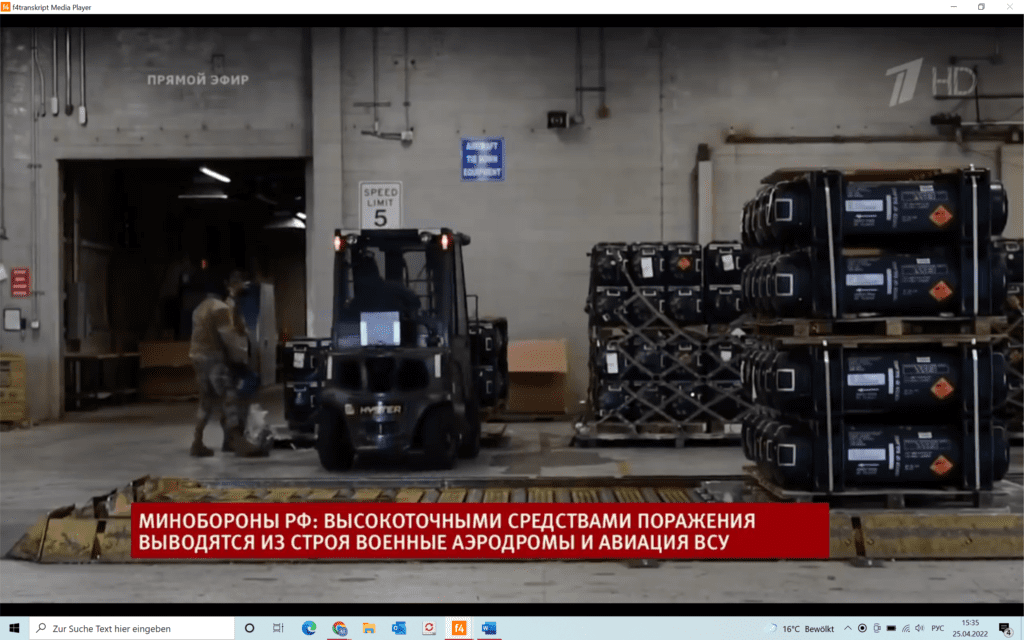

The alleged Ukrainian aggression against Russia is also supported visually. In the show’s episode, a video depicting piles of barrels is projected onto the large studio screen, and Anatolii Kuzichev, one of the moderators, explains that with these barrels Ukraine is trying to “threaten” (pugat’) Russia (see fig. 3).

However, the key information that by journalistic standards should be shown—where this video was taken and what is inside these barrels—remains entirely unknown to the viewers. Notwithstanding these flaws, the pictures are likely to achieve their aim of presenting the Ukrainian side as the actual aggressor, thus purportedly justifying Russia’s need to defend and protect itself.

***

In sum, the first broadcast of the Vremia pokazhet talk show on Russian state-run TV channel Pervyi kanal on the very first day of the escalated invasion of Ukraine, 24 February 2022, mainly repeats the statements of the Russian president that he had proclaimed in the morning of the same day. Still, some of the legitimizations of the “special operation,” such as the liberation of Ukraine or Russia’s portrayal as a peacemaker, are not new, as they were already used in 2014. Since then, they have constantly been repeated on state-owned Russian television, thus preparing Russia’s population for the upcoming military invasion of Ukraine.

[1] In Ukraine they are referred to by the acronym “ORDLO” (occupied districts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts).

[2] From 1929 to 1961 the city of Donetsk was named Stalino.