Identities and attitudes toward Ukrainian ethnopolitics: A population survey

Abstract

A recent representative nationwide survey provides information on how multi-level identities interact in contemporary Ukraine and shows that inhabitants across different ethnicities and regions report a strong attachment both to their local community and to the Ukrainian state. Inter-ethnic relations are perceived to be quite good, and better at the local community than the national level. The survey reveals great variations in popular assessments of Ukraine’s policies toward its ethnic minorities. Tensions between socio-economic groups are perceived to bring more local disunity than tensions between people with different ethnic or linguistic backgrounds.

Ukraine is well known for its marked ethnic, linguistic, religious, regional, and socio-economic cleavages and for its diverse and overlapping identities. These cleavages and identities at times get politicized—the conflict in Donbas, changes in language legislation, decommunization laws, and memory politics being apparent examples. How do these multiple identities interact in contemporary Ukraine, and how do ordinary Ukrainians assess ethno-cultural relations and the current regime’s ability to accommodate the country’s vast ethno-cultural diversity? A sociological survey conducted in December 2020 as part of the Ukrainian-Norwegian ARDU project (Accommodation of Regional Diversity in Ukraine) sheds light on these questions. The survey was conducted by the Operatyvna Sociologia opinion poll agency in Dnipro, which carried out a total of 2,103 telephone interviews with a representative sample of Ukrainian citizens across the country.

Strong multi-level identities

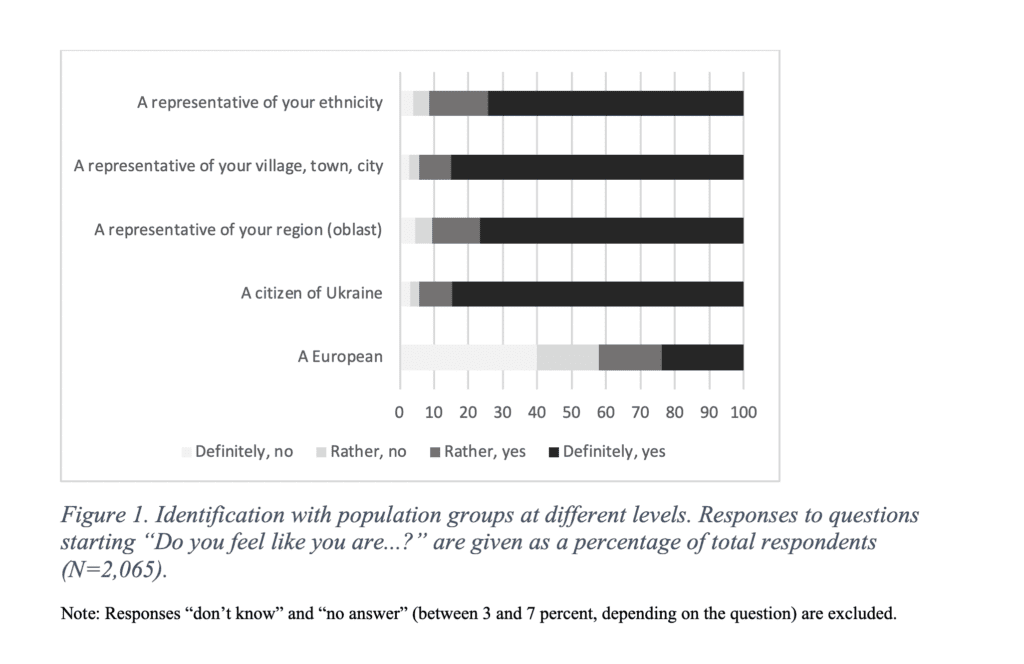

This survey set asked respondents to what extent they feel they belong to communities and places at different levels, ranging from being a representative of one’s ethnicity to being a European. The results are displayed in Figure 1.

With the marked exception of feeling European, responding Ukrainians identify quite strongly with the other questions in this set—and especially at the level of their local communities (village, town, or city) and with their Ukrainian citizenship. Ethnic and, especially, regional identities are also reported to be very strong. Furthermore, there is a strong correlation among the different types of identity, such that those who report a strong identification with one of the questions have a strong likelihood of identifying with the other ones. Thus, layered identities are commonplace and appear to reinforce one another. The weakest correlations are found between feeling European and the other attachments.

The strong correlation between most of the questions in this set signalled to us that it would be interesting to compute an aggregate index, which we called an “index of belonging,” that ranges from 0 (no belonging) to 3 (strong belonging on all the identity questions except the European one, which was excluded from this index). Moreover, based on respondents’ ethnic self-identification (“What ethnicity/natsional’nist’ do you consider yourself belonging to?”), our analysis showed that declared ethnic Ukrainians (index score 2.7) and those declaring mixed ethnic identity (2.6) have a higher score on the “index of belonging” than declared ethnic Russians (2.4) and those declaring other ethnic identities (2.3). Regional differences are small, but people in the western part of Ukraine report a slightly stronger sense of belonging (2.8) than people in the east and centre (2.7) and south (2.6). Older age and economic well-being also associate with a stronger sense of belonging according to our survey data, while on the other hand respondents’ gender and education are not statistically significant factors. The main finding overall, however, is that Ukrainians on average display strong regional and ethnic identities, and that this is the case across the country as well as among respondents of different ethnic backgrounds (86 percent in the survey identifying themselves as ethnic Ukrainians, 6 percent as ethnic Russians, 4 percent as another ethnicity, and 3 percent reporting a mixed identity; 1 percent were unsure or gave no answer).

Inter-ethnic relations in local community better than in Ukraine as a whole

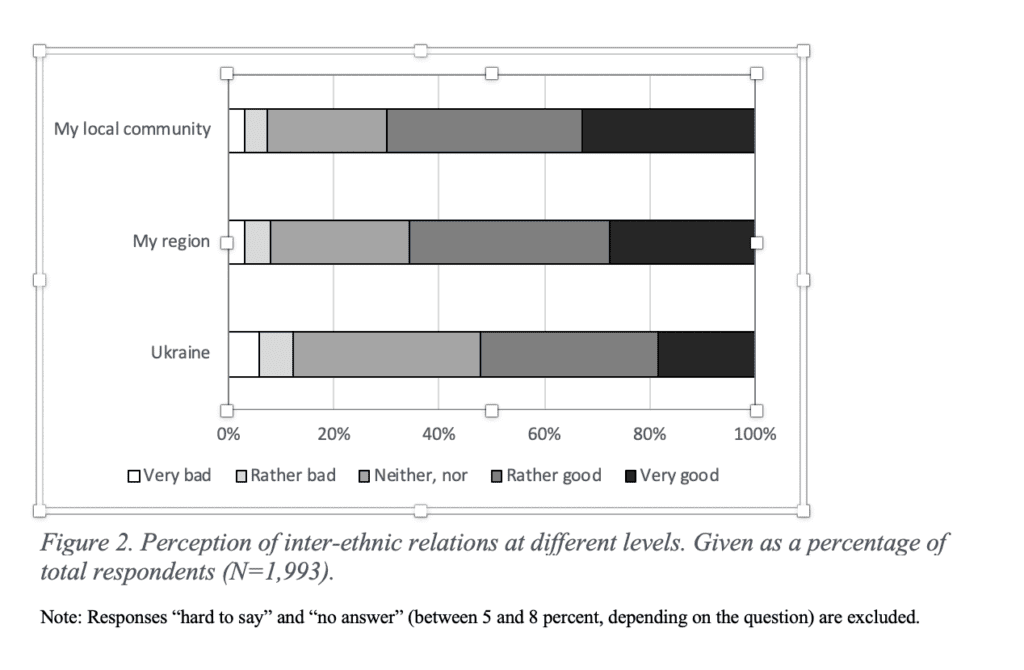

Our survey data show that comparatively, there is some variation in how respondents perceive inter-ethnic relations at the level of their local community (village, town, city), region, or national level, as displayed in Figure 2. Regardless of the level, few respondents consider such relations to be rather bad or very bad. Furthermore, respondents are inclined to perceive inter-ethnic relations in their local community to be somewhat better than in the country as a whole, with regions in between.

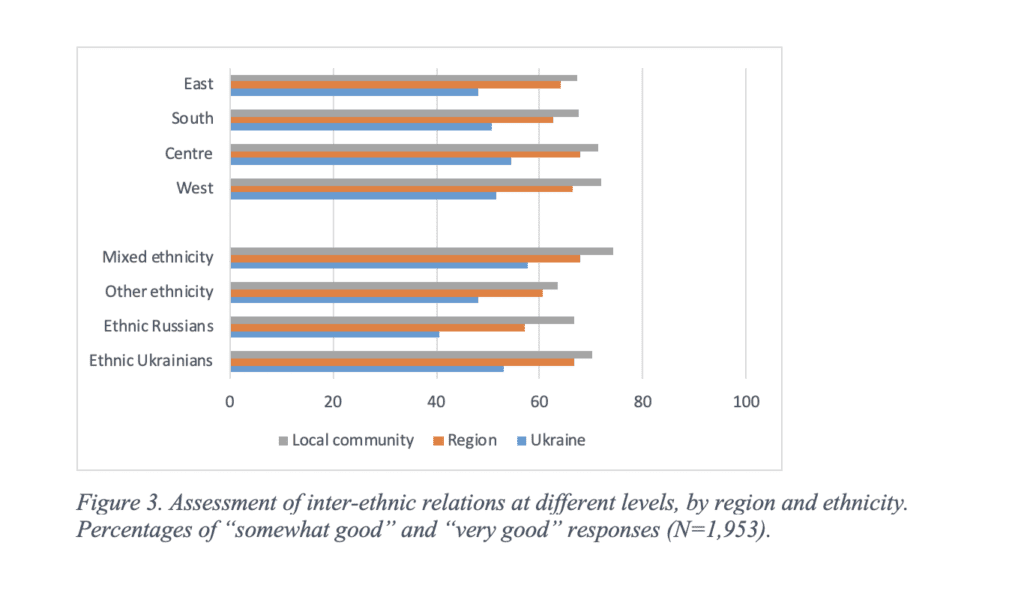

Figure 3 provides more details by displaying the data for respondents of different ethnicities and from different parts of the country. The general patterns are the same for all groups: inter-ethnic relations are perceived to be best at the local community level, followed by the regional and national levels. Moreover, ethnic Ukrainians and, especially, those reporting mixed identity give more positive assessments of inter-ethnic relations than do ethnic Russians and representatives of other ethnic groups, regardless of the levels assessed. As for regional differences, respondents in the western and central parts of the country report the most positive assessments of inter-ethnic relations, but the differences are very moderate and smaller than the differences between ethnic groups.

Inter-ethnic relations not the main cause of disunity at local level

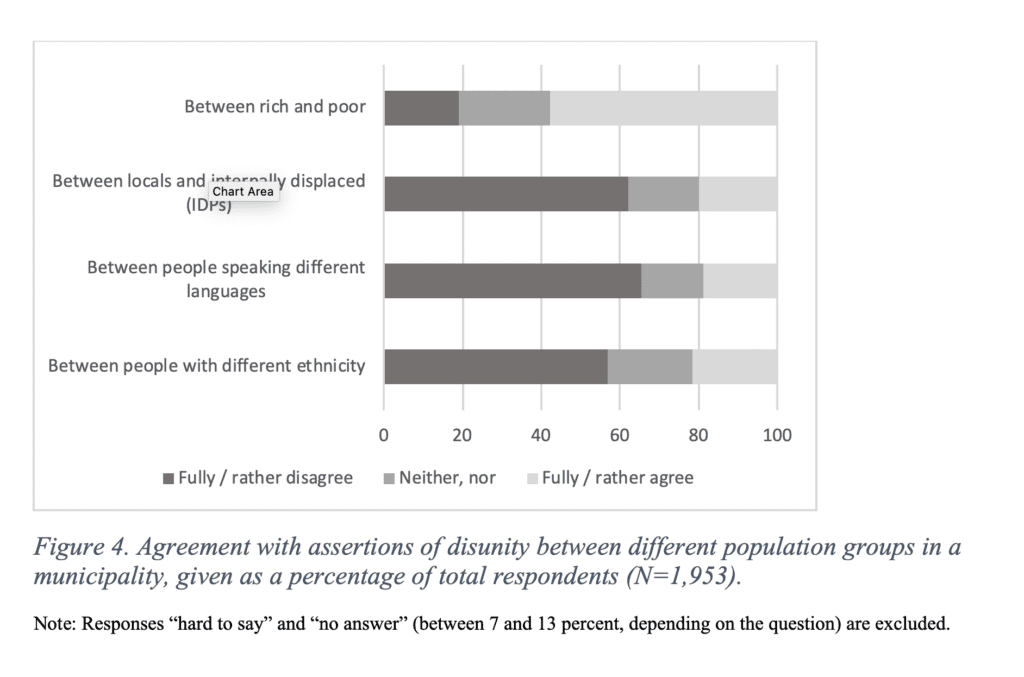

Even though the majority of Ukrainians perceive inter-ethnic relations to be somewhat or very good in their local community, it is nevertheless worth identifying to what extent disunity between respondents of different ethnic backgrounds is a major concern or whether other types of local disunity are more important in Ukrainians’ everyday lives.

Figure 4 illustrates how inter-ethnic disunity is perceived compared with other potential sources of local conflict. Respondents were asked to what extent they agree with a statement that there is disunity between different population groups in their municipality. It is striking that disunity between rich and poor is perceived to be much more prevalent than between groups with different ethnic, linguistic, and migrant backgrounds. Further analysis shows that there are only small and not statistically significant differences in the way representatives of different ethnic groups and people from different parts of the country assess group relations in their municipality.

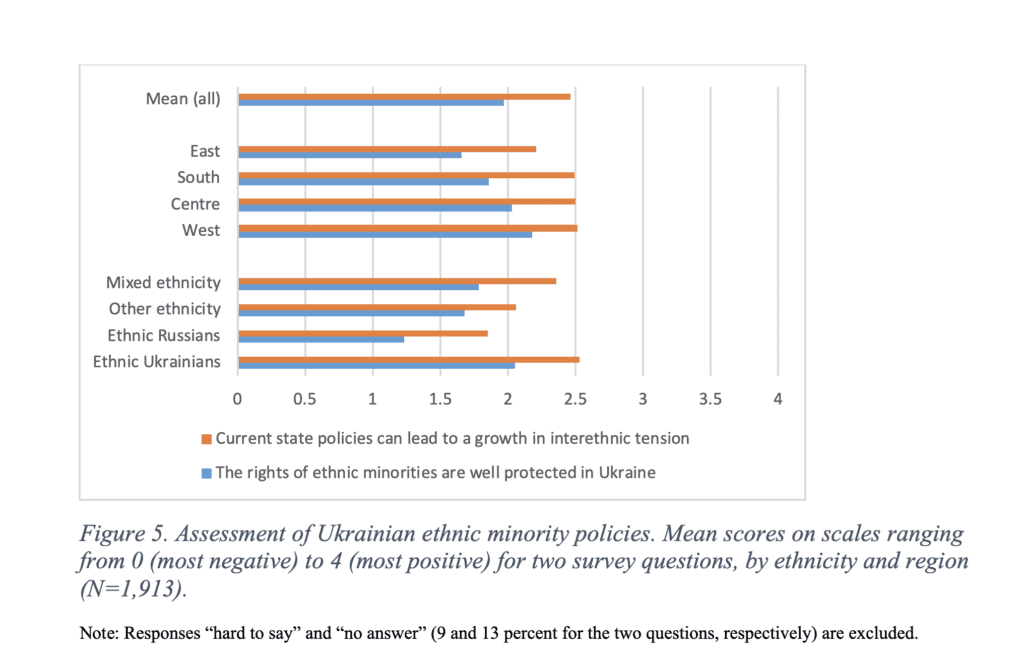

Mixed assessments of Ukrainian ethnicity policies

Our survey reveals great variations in respondents’ of Ukraine’s policies toward its ethnic minorities, as assessed in the answers to two survey questions. Respondents were first asked whether the rights of ethnic minorities in Ukraine are well protected and, second, whether current state policy could lead to any growth in inter-ethnic tension. Figure 4 shows the mean scores for each of the two survey questions on scales ranging from 0 (most negative: fully agree for question 1, fully disagree for question 2) to 4 (most positive: fully agree for question 1, fully disagree for question 2) for different categories of respondents.

The majority of respondents do not give a particularly positive assessment of the protection of minority rights in Ukraine, with a mean score just below the middle of the scale. However, when asked whether current state policies could lead to increased inter-ethnic tension, they on average lean slightly toward the more positive end of the scale. For both survey questions, ethnic Russians as a group are more skeptical than other ethnic groups about current state policies toward ethnic minorities, with ethnic Ukrainians at the opposite end. Still, rather large numbers of ethnic Ukrainians do have rather negative views on these issues. When it comes to regional variation, respondents in the eastern part of the country are the least likely to give a positive assessment of Ukrainian minority policy.

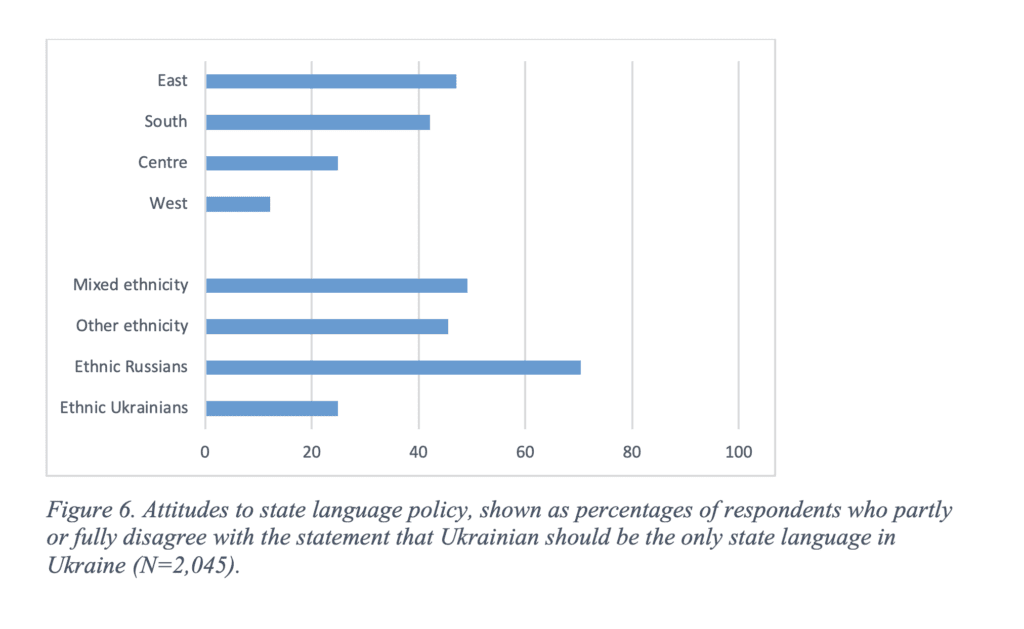

Since a large share of respondents identifying as ethnic Ukrainians also use Russian as their language of communication, language policy is not solely an ethno-political issue. Nevertheless, one would expect ethnic Russians to be more prone to support policies that grant official status also to the Russian language. The survey question about whether Ukrainian should be the only state language in Ukraine illustrates the large discrepancy in views on this contentious issue in Ukrainian politics: While a majority (58%) of the respondents fully agree with such a proposition, over one-quarter of the respondents either fully (20%) or partly (7%) disagree with it.

Figure 6 shows who are the most likely to be opponents of Ukrainian as the only state language. A deep ethnic divide can be observed on this issue. More than two-thirds of ethnic Russians oppose the proposition, with considerable agreement among those of other non-Ukrainian or mixed ethnic identities, as well. When it comes to regional variation, the figure (as expected) displays opposition being most widespread in the eastern and southern parts of the country. Further analysis shows that a majority of ethnic Ukrainians who do not use Ukrainian as their main means of communication still support Ukrainian as the only state language (53% either fully or partly support this, compared to 74% of ethnic Ukrainians who report Ukrainian as their main language).

Conclusion

Three findings from our survey are worth highlighting because of their implications for Ukrainian ethnopolitics. The first is that all population groups, regardless of ethnicity and geographic residence in Ukraine, express a strong identity with their place of residence at various levels, ranging from their local community up to the national level. Furthermore, these attachments are shown to be mutually reinforcing, so that one identity is usually not chosen at the expense of another. The second is that Ukrainians give a rather positive assessment of inter-ethnic relations in their own community, which are perceived to be better than such relations at the national level. Thus, inter-ethnic tensions, especially in everyday encounters, are not a major concern for the majority of Ukrainian residents. The third is that other group tensions, especially those between rich and poor, are perceived to bring more local disunity than tensions between respondents of different ethnic or linguistic backgrounds.

What, then, are the implications of these findings for Ukrainian ethnopolitics? The strong attachments to place that are expressed at all levels, from local to national, shows that ethnic identity is not the main identity marker for Ukrainian residents. This should facilitate policy solutions that cut across ethnocultural boundaries. Reforms that promote unity at the local level—such as Ukraine’s successful decentralization reforms—could therefore contribute to strengthening national unity in the country as a whole. Still, the survey also shows that certain political issues, such as language policies, have the potential to stir tension between groups.

To strengthen social cohesion across inter-ethnic and regional boundaries in Ukraine, it seems that policies aiming to solve socio-economic challenges would be more important than those addressing inter-ethnic issues. Our survey thus complements the findings from other studies that show—aside from the war in the Donbas—issues such as large-scale corruption, unemployment, and inflation are of much greater concern to Ukrainians than ethnopolitical issues. The marked regional and ethnic divides along both voting patterns and geopolitical orientations in Ukraine are well known. However, the attachment that the vast majority of Ukrainians, regardless of their ethnicity and geographic place of residence, express both to their local community and to the Ukrainian state is a great resource that Ukrainian political leaders should handle with care. Finally, based on the views indicated by the survey respondents, there is room for improvement in the area of Ukrainian ethnopolitics.

Bibliography / further reading:

The ARDU project has been financed by the Research Council of Norway (project no. 287620) and includes participants from Ukraine, Norway, and Germany. For details and other publications from the project, see the project website. See also the forthcoming book: Aadne Aasland and Sabine Kropp (eds.), Accommodation of Regional and Ethno-cultural Diversity in Ukraine, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021. For details on the survey methodology, see Vladislav Baliichuk (2020), ‘The methodology of the ARDU survey’ (in Russian).

This manuscript was first published in German in Ukraine-Analysen no. 254.