Ukraine in the post-truth environment, or Future shocks of the global village

When I was a graduate student in Odesa, I liked reading Alvin Toffler and Marshall McLuhan. Both were futurologists theorizing about the impact of information exchange on societies. In the late 1960s, Toffler came up with the concept of future shock, while McLuhan “invented” the global village. I enjoyed combining these two concepts into a sort of “theory of everything” (I bet I was not the only one).

Future shock manifests itself in our unpreparedness to embrace the future and find our place in the world of tomorrow. On the road from an industrial to a post-industrial society (aka the Third Wave), we suffer from information overload. According to Toffler, the world around us no longer has a history. Everything changes too fast for us to record and remember: from new shops opening in your neighbourhood to new wars starting overseas. Even when scrolling newsfeeds on social media, the moment eventually comes when we are no longer able to read into the messages, not to speak of distinguishing true from false. This can be scary.

Speaking of the Edmonton-born McLuhan, in today’s context his global village is predominantly a product of electronic interdependence, which draws from the drastic improvement in technologies and accessibility of means of communication. This interdependence has led to the emergence of a planetwide community where borders, time zones, and geographies are not that important. We can watch in real time what Russian President Vladimir Putin says about his country’s “non-presence” in the Middle East and discuss the significance of the colour of his tie. We gradually move from individualistic thinking and social fragmentation to a “tribal” collective affiliation. Or do we?

What I failed to realize back then, in Odesa, was that the combination of future shock and the global village would contribute to the post-truth world we are experiencing today. I simply could not even imagine something like post-truth. It is merely a by-the-way observation, however, outside the scope of this article.

Returning to the most recent times, on the eve of the 2015 parliamentary elections in Poland I spoke to my friend Michał Kuź, who noted that identity politics was gaining momentum. With it has risen the public importance of nation-states and sovereignty. This happened because “conservative values” have provided solid points of reference for a number of people who started feeling “lost” and “scared” in the shocking environment of the global village. At first, I didn’t pay much attention to Michał’s deduction. For me, nothing could challenge the ascendancy of the liberal democratic order. Under ideal circumstances, in fact, the presence of a state in my life should have been diminishing with every new day.

By the mid-2010s, however, I was proven wrong.

The 2015 victory of the conservative Law and Justice party in Poland came “unexpectedly.” Then, again “unexpectedly,” the results of the UK referendum on Brexit landed like a bombshell. Then Donald Trump became the US President. And since then, elections in Austria, Italy, Hungary, Germany, France, and the UK have manifested, to one degree or another, social demand for the endorsement of national identity and implementation of “easy” solutions within the narrow boundaries of sovereign interests.

I was compelled to review my beliefs concerning modernity.

Today, I think that our era signifies a return to nation-state-centrism, often pushed by populist leaders who praise confidence over competence or necessity. As for the citizens, their quest for comprehensive order is so overwhelming that they even agree to tolerate political self-harm if it grants them a feeling of predictability in their lives and satisfaction with their immediate environment.

Now let us return to Ukraine. It has a profound post-modern (post-truth?) dilemma. On the one hand, its citizens and political elites are inevitably influenced by the global trends of populism and searching for easy solutions. On the other hand, its neighbours have switched to nation-state-centrism and are often wont to promote assertive anti-Ukrainian agendas. The dilemma is exacerbated by the fact that Ukrainians lack the sense of strong sovereignty and nationhood that their neighbours have and make use of.

In the most aggressive and egregious instance, Russia is escalating the pursuit of its longstanding imperialist and expansionist policies. Russian elites continue to maintain that Ukraine is an artificial state, that the Ukrainian language and identity were created by enigmatic Russophobic powers, and that Ukrainians and Russians are one people. Repeating its mantra of protecting compatriots abroad (which also constitutes a provision in its official “Military Doctrine”), Russia projected its sovereignty onto Ukraine’s Autonomous Republic of Crimea and heavily supports its proxies in the Donbas. Russian citizens perceive their state’s activities in Ukraine as a sign of its national—and, by extension, global—greatness. Oppositely, Edward Lucas defines it as an attempt to construct a soft empire in the post-Soviet space.

Elsewhere, Poland seems to be on a mission to introduce versions of historical justice that would satisfy its conservative citizens. While Ukrainians attempt to turn the page on the twentieth century and move into the future, Poles—especially the so-called Kresowians—want to bring clarity to the issues of the past. The current Ambassador of Poland to Ukraine, Bartosz Cichocki, has resolutely taken up the cause, in the first days of 2020 issuing an aggressive statement in reaction to Ukraine’s commemoration of Stepan Bandera and other figures of Ukrainian nationalism. This, inter alia, may be interpreted as a projection eastward of Polish sovereign interests. At the same time, economic and energy relations between Poland and Ukraine have never been better, as both states favour pragmatism in this field.

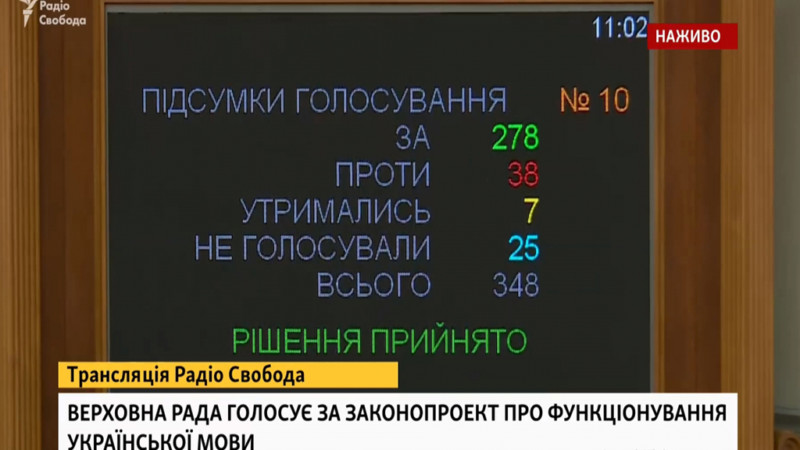

Hungary’s attempts at a power play in Ukraine look even harsher than Poland’s. It seems that Budapest has unilaterally defined the interests of a part of the Ukrainian population that has a connection to Hungary and assumed the responsibility of acting on their behalf. For instance, in 2018 the position of Commissioner for Transcarpathia was introduced in the government of Hungary. Prior to that, Hungary decided to impede Ukraine’s integration into the EU and NATO in retaliation for its 2017 Law “On Education,” which made Ukrainian the compulsory language of education across the country. In a word, Budapest is not limiting itself to discussions of historical disagreements—which is one of Warsaw’s key objectives—but is trying to get much deeper into Ukraine’s sovereign policies. Again, it is possible thanks to the indifference or even outright connivance of ordinary Hungarians.

Next we have Romania, cautious in its statements and actions but closely monitoring Ukraine’s Bukovyna region, where ethnic Romanians reside. Romania is also not very happy with the 2009 resolution of the Zmiinyi Island dispute and opposes construction of the Bystroe Canal today. For its part, Turkey occasionally plays on “team Russia,” when both states pursue the politics of national greatness. As the Turkish political scientist Şener Aktürk once said, Turkey and Russia are “friends in times of weakness, while foes in times of strength.” In practice, this means that Ankara’s actions and words regarding the status of Crimea do not always reconcile, and it is in no rush to launch a long-promised free-trade area with Ukraine. It seems that only Slovakia, Moldova, Belarus, and Georgia have raised no unilateral sovereign queries to Ukraine.

In this light, Ukraine is being strategically pricked from many sides by its immediate neighbours. To make things worse, while the elites of the majority of neighbouring states boldly exploit national myths to gain extra legitimacy and appeasement among their citizens, Ukrainian elites is not able to do this unequivocally. The reason for this is that Ukraine has not yet managed to consolidate itself as one comprehensive source for such myths. Some Ukrainians perceive Soviet-type internationalism as the best foundation for sovereignty, others expect to have the EU’s acquis introduced immediately, some find salvation in the old interwar nationalist dreams, and still others go as far back as propagating restoration of the Cossack semi-statehood. Not to mention that the elites themselves lack a distinctive historical tradition of statecraft.

With this in mind, the election of Volodymyr Zelensky as the president of Ukraine presents a very curious case. Frankly, Zelensky was no more than an anti-establishment provocateur with little political experience and predominantly indirect communication with the voters (he calls it electronic democracy or “state in a smartphone”). Oleksii Polegkyi defined him as a magician who capitalized on social emotions and used humour to promise he would bring them their long-awaited fabled “stability.”[1]

Zelensky acted confidently—though often clumsily—and exploited the new electronically interdependent media. He convinced voters that he would “accommodate” the future shock and thus became a global village pooh-bah. He played the role of an easygoing guy who offers simple solutions to complex questions with a smile. Considering this, his record-high 73.22 per cent of voters’ support looked convincingly like a landslide. Zelensky also proved that Ukraine’s political life is much in line with global trends: his easygoingness “united” Ukraine and launched a new post-truth stage in the state’s history. However, what is not in line with global trends is the weakness of Ukraine’s reliance on its sovereign tradition, which the new president cannot benefit from or use as an effective bulwark against assertive external actors.

As I mentioned in one of my interviews, Ukraine is catching up with history (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=28LE-kcEEbI). It needs to discover and reinforce its national identity—a task that the majority of its neighbours are close to completing. Ukraine disposes of very little time for this. On the one hand, the pressure of sovereign interests from Ukraine’s neighbours is sure to further increase. On the other hand, the political rules of the post-truth world will remain flexible and relative. Convictions of voters will change depending on the messages they receive. And it hardly needs mentioning that these convictions will often prevail over the power of reason and voices of competence.

To make things worse, fuelled by fatigue and future shock, sooner or later the actors that Ukraine can trust, such as the EU, US, UK, and Canada, are likely to switch their focus and resources to where their sovereign interests lie—in other regions of the world, for instance, to the Middle East.

This decade, starting with 2020, will be of existential importance for Ukraine, as well as for that whole region. The rest of the global village would be well advised not to ignore it.

=====

Ostap Kushnir is an assistant professor at Lazarski

University (Poland) and lecturer at Coventry University (UK). He holds an M.A.

in Journalism from Odesa Mechnikov National University, an M.A. in

International Relations from the University of Wales, and a Ph.D. from Nicolaus

Copernicus University in Toruń. His academic interests include geopolitical and

identity-forming processes in Central and Eastern Europe, specifically in

Ukraine and the Black Sea region. He is the author of Ukraine and Russian

Neo-Imperialism: The Divergent Break (2018) and editor of The

Intermarium as the Polish-Ukrainian Linchpin of Baltic–Black Sea Cooperation (2019).

[1] https://ukrainian-studies.ca/2019/08/13/ukraine-in-search-of-a-magician-from-protests-to-the-victory-of-populism/