Video: The Forty-Eighth Annual Shevchenko Lecture

The Forty-Eighth Annual Shevchenko Lecture, Professor Tamara Hundorova’s “A Different Shevchenko: What Is Kobzar Darmohrai Speaking About?”

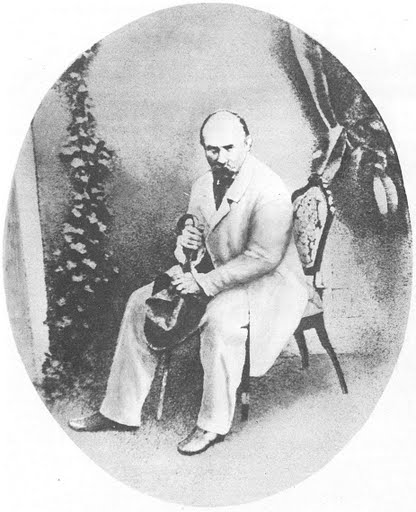

Featured Image: Portrait of Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861) by Ivan Kramskoi. Source: Wikipedia.

About the Forty-Eighth Annual Shevchenko Lecture

8 April 2014—This year’s annual Shevchenko Lecture, organized by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, and co-sponsored with the Ukrainian Professional and Business Club (Edmonton), featured a presentation by Professor Tamara Hundorova, an internationally renowned scholar in the fields of literary studies, modern literary theoretical concepts, modern Ukrainian literature, cultural studies, and literary criticism.

Tamara Hundorova (Department of Literary Theory, Shevchenko Institute of Literature, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine) received her doctorate in philology in 1996 and became a corresponding member of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in 2003. Since 2002, she has headed the Shevchenko Institute of Literature. Professor Hundorova is the author of ten monographs, including Kitch i literatura. Travestiï (Kitsch and Literature: Travesties; Kyiv, 2008) and Nevidomyi Ivan Franko. Hrani izmarahdu (The Unknown Ivan Franko: Facets of the Emerald; Kyiv, 2006), as well as numerous articles, book chapters, and other works published in Ukraine and abroad.

Few people seem to know that Taras Shevchenko wrote prose as well as poetry. Although there were reasons for his prose texts to remain largely obscure to literary scholars, and even more so to the general public, this aspect of Shevchenko’s rich legacy offers a unique perspective on a deep and highly personal relationship between the poet and his beloved fatherland, Ukraine.

Besides the spirited Kobzar (minstrel) known to us from Shevchenko’s poetry, his work features another self-representation—Kobzar Darmohrai (“the one who plays for free, for the love of playing”). This doppelgänger is omnipresent in Shevchenko’s Russian-language prose. Indeed, the author seemed to change proverbial literary masks as effortlessly as he changed peasant clothing for the attire of a person of higher social standing. Nonetheless, it would be an overstatement to maintain that the sole purpose of Shevchenko’s writing his prose in Russian was to address readers in the Russian imperial capital, St. Petersburg, and to publish his prose works there.

Some scholars maintain that Shevchenko’s Russian-language prose was meant to appeal to his Ukrainian (Little Russian) compatriots—representatives of the petty gentry and landlords whom he met in Ukraine and whose contribution to his Ukrainian identity was greater than that of members of Ukrainian national “brotherhoods.” Shevchenko’s mask of an author speaking and writing in Russian and addressing the so-called “middle class” of his time proved quite different from his “Ukrainian mask,” displayed in a letter from exile to his compatriots active in the Ukrainian national movement.

Indeed, a textual analysis of Shevchenko’s prose demonstrates the richness of his arsenal of literary disguises. Shevchenko differentiated himself from Darmohrai, as the following phrases attest: “Once I told Darmohrai…,” “He has sent me…,” and “He is much less affluent than I….”, as well as presented himself as an acquaintance of Darmohrai (he came to visit “…one artist…Shevchenko”). All in all, Shevchenko’s Russian-language prose is replete with play, irony, and deliberate mystification.

In allowing Darmohrai to speak, Shevchenko played with his imagination, splitting his personality—a narrator and listener on the one hand, an author and literary character on the other. Shevchenko’s choice of Darmohrai as a disguise served an important therapeutic function, helping him overcome the social, geographic, and cultural isolation of exile. Thus Darmohrai became an agent of Shevchenko’s memory. Separated physically from his friends and his native land, Shevchenko–Darmohrai wandered the expanses of his beloved Ukraine in imagination, remembering places he had visited and people he had met.

Simultaneously, Shevchenko created Ukraine as an imagined entity, using descriptions based on ideas of ethnic and social transformations that were important to him—projections of his “ideal” perceptions. Those transformations involved human characters, languages, clothing, and landscapes. Geography was also important, as Shevchenko meticulously recorded routes that he had travelled: from Moscow to Kyiv and from Kyiv to Pereiaslav, Poltava, Pryluky, Hlukhiv, and Sorochyntsi. In one of his stories, “A Delightful Stroll Not Without a Moral,” Shevchenko offers a vivid composite portrait of his female “compatriot,” a member of his audience whom he likely addressed in his thoughts. This image must have served as Shevchenko’s ideal embodiment of his mother, of Ukraine, and of a future wife. The image of a maiden compatriot figures in Shevchenko’s symbolic mystification: a newlywed heroine does not recognize Darmohrai in the dark, thinking that he is her husband.

In another story, Darmohrai engages in masquerade, exchanging clothes befitting a lord for those of servant in order to join the common people’s festivities. This symbolic change of identity allows Shevchenko to join his characters, with whom he shares language, social status, culture, and ethnicity. On seeing the lord dressed in peasant clothes, the common people drop their “unnatural Great Russian language and [speak] to me in theirs, the Little Russian [language].”

To Shevchenko, the use of masks and disguises proved his ability to masquerade, play, and take on alternative identities. Darmohrai thus reveals to us a Shevchenko very different from the iconic image of him that we all have learned to know and cherish.