Interview with Volodymyr Yermolenko | We’re losing the “balance of fear”: Russia is not afraid of the West, but the West is afraid of Russia

Oleksandr Pankieiev: For most people, living through a time of war is an extremely difficult and life-threatening experience. As a philosopher, what are some of the personal and philosophical challenges you have faced during the war that Russia has unleashed against your country?

Volodymyr Yermolenko: I am trying to rethink many philosophical questions, because the war gives us this liminal experience. Of course, it poses a significant threat, but it also offers us an opportunity to rethink some of the fundamentals.

The way we approach life’s questions is very different now. In peaceful times, everyone knows that they will eventually die, but we mostly believe that death will happen at some remote period. During war, you lose the confidence that you have time. We can say that life accelerates. You approach life from the thought that tomorrow may not come. As a result, you cherish life more intensely and try to appreciate the good things around you more.

The second factor is that war is a time of extremes. It is extreme hatred, but also extreme love. It is extreme death, but also extreme life; it is extreme sadness and tragedy, but also extreme happiness. Everything becomes much more acute. We move away from a given middle ground. This can be good and bad at the same time, but it is the reality of war.

Time is also perceived differently during the war, because it accelerates. I write about how we perceive time during war being very close to the concept of time in classical drama. To recognize yourself in this time, you should not read Proust but rather Shakespeare or Lesia Ukrainka, because time changes very quickly and it is faster than you. In a way, you become a prisoner of this speed.

Of course, the question of good and evil and the relativity of values arises as well. In peacetime, people can live very cynically. However, wartime introduces grand ideas and the issue of values into our lives, prompting us to distinguish between good and evil. I reflect on this issue in my texts quite a bit. What is evil? What is violence? Why do people want it?

Pankieiev: My next question is related to all the concepts you just mentioned—evil, life, and death. Human history has produced a lot of knowledge on these concepts. Why do we need to reconsider them again? What is the epistemological value of thinking about them at this moment?

Yermolenko: I do not think that people ordinarily possess knowledge that is valid for everyone and for all epochs. I’m a philosopher who thinks about history in a cyclical way—not in a progressive or regressive way. I consider myself a pupil of thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, and Polybius, in how they view the world as anacyclosis, or as a cycle between different forms of government, such as monarchy, aristocracy, democracy, and tyranny, among others.

I consider this cycle through a broader set of variables, asking what is more important, the individual or the collective? I look at questions of light versus darkness. There are epochs in which people start thinking from darkness, such as in the Baroque period or Romanticism, and now our own age. Another tension arises between spirituality and corporeality. For instance, the 20th century was marked throughout by the emancipation of bodies. By contrast, we are now returning to a century of bodilessness in a way. The digital age is an entrance into a non-material reality which strikingly resembles the reality dreamt about by Baroque and Romantic mystics.

When I say we should rethink ideas of good and evil or life and death, I don’t mean that this rethinking leads to something we’ve never experienced. My intellectual canon is different from the intellectual canon of people living during peacetime. For me, the truly insightful thinkers are those who emerged from dark times, such as Walter Benjamin, Blaise Pascal, Karl Jaspers, and Hannah Arendt. They are, for the most part, pessimists who did not believe in utopias, who were attentive to the fragility and dark side of human beings and tried to avoid naīveté. Many thinkers in the Ukrainian tradition have also influenced my way of thinking—the main one being Lesia Ukrainka. She knew what it meant to live in times of radical change and darkness. She was a pupil of great playwrights, and drama is born in dark times.

I believe a lot of valuable thinking comes from dark times, and therefore I titled my podcast “Thinking in Dark Times.” I’m also considering publishing a book with the same title, to collect my ideas. I don’t think that darkness equates to bad things. We often see better in the darkness. A soldier friend sent me a gift recently and wrote on it, “Dark times produce bright people.” It’s an amazing phrase. The darker the times, the brighter people become. There is something quite insightful in this thought.

Pankieiev: It is a really good phrase, because right now Ukraine is producing both ideas of both darkness and light. Do you see Ukraine currently contributing to “light” or “positive” philosophical thinking, as it were?

Yermolenko: Yes, I believe so. I always say that Ukraine is a nation of “despite.” There is positive freedom—”the freedom to”—and there is negative freedom—”the freedom from”—but there is also “freedom despite,” which asserts itself in a situation when freedom seems impossible. “Despite” (vsuperech) is always pushing back on the boundaries of the impossible. It is searching for positivity in a situation where others would say that positivity, happiness, or joy are no longer possible. Ukraine’s experience shows us that these feelings are possible even in situations where it seems impossible. This is an incredible story about human beings. This is perhaps one of the key ideas of human nature, because human culture is about how we push back the boundaries of the impossible, how things that seem to be impossible for some generations become real for others.

Pankieiev: Speaking of processes, at CIUS we often discuss the urgent need to decolonize Russian and Slavic studies, which have long been shaped by a Russocentric view of the region’s history and culture. In contrast, you raise the issue of the re-imperialization of the world. These appear to be two opposing dynamics—one aimed at dismantling imperial legacies, the other at reviving them. Which of these forces is prevailing in today’s world?

Yermolenko: I think re-imperialization currently prevails in the world. De-imperialization as a process has come in different waves. It had a wave in the late 18th century, and Canada and the USA are probably a product of that particular wave. Then there was de-imperialization in Latin America and de-imperialization of Central Europe and Southern Europe, such as the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg Empire. Then there was the de-imperialization after the Second World War.

It’s remarkable how Russia has succeeded in re-imperializing itself after every wave. In one sense, the Enlightenment was a period of de-imperialization, while for Russia it was a period of re-imperialization. Imperial Russia’s conquest of parts of Europe was followed by its expansion throughout the 19th century and then collapse after the First World War. Then we see its re-imperialization in the form of the Soviet Union, followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991—and now, its re-imperialization under Putin.

Russia’s neoimperial ambitions present a seductive temptation to the world at present. People with imperial ambitions are encouraged to believe that their ambitions are achievable and that decolonization processes are an aberration, a wrong that will inevitably be righted. The Kremlin’s propaganda actually aims to convince the world that decolonization is a doomed endeavour and that collapsed empires can re-imperialize and re-establish their power. (Another matter is that Russia cannot re-imperialize without its former colony Ukraine, which is the main motivation for this war.)

It’s obvious that Putinism is a model for Trump. I always tell Americans from the United States that the danger of Putin is not far away. The ocean no longer separates you. Putin is already inside your country. People believe that an open society and globalization are a way to spread ideas about liberal democracy. However, they forget that all ideas spread in an open world—the good and the bad. Now is a time when bad ideas are spreading.

Instead of the Americanization of Russia, we now have the Russification and Putinization of America. This is the appeal of re-imperialization, and I think it will remain attractive for a very long time. At a certain point, the Western world—which has been living under remorse for its imperial past over the past few decades—will need to understand that it is becoming a colony itself—either of China, Russia, the United States, or the oil-producing Arab world. This is happening in Europe right now. Remarkably, these former empires will need to undergo decolonization themselves. Here, the experiences of Ukrainians, the whole of Central Europe, and the Balkans will be of great help. However, we have not grasped this reality yet.

Pankieiev: It seems like Francis Fukuyama’s article “The End of History” needs to be rewritten with the same title, but with completely different content for this moment.

Yermolenko: Fukuyama should not be dismissed. Many people read only the title of his article. As far as I understand, Fukuyama’s message was that we are approaching an end of history—in which drama disappears, when Shakespeare is no longer possible. All the best drama portrays conflict over value systems. Shakespearean dramas mostly involve conflict between the pagan and Christian worlds, as seen in Macbeth and Hamlet. In the case of Lesia Ukrainka, Ukraine’s major dramatist, we also see a conflict between different value systems. In every one of her dramas, you see different worlds in conflict with each other. Rufinus and Priscilla is a conflict between the Christian world and the ancient Greek and Roman world. Or The Stone Host is a conflict between the values of sacrifice, free love, and power.

Fukuyama meant that we are approaching a moment when the conflict between value systems disappears. This is the end of history, but actually it will not come to pass. People will not be satisfied with it. Fukuyama posed the question of whether people living at the end of history will be bored. In his own answer, he asserts that is very boring to live at the end of history, and people will reinvent history. I think he is correct, and this is what is happening. We are in the midst of history’s reinvention.

Putin wants to portray himself as a conservative—an antidote to modernity. This is his own delusion, since he is a product of modernity, but he’s searching for something else. Therefore, he invents this idea of Eurasian Christianity. He has nothing to do with Eurasian Christianity, but he invented it to reinvent history. History is always tragic, because if you want to begin history anew, you must kill a lot of people. That is the other side to it. What will we do? Should we choose the end of history, which is boring but saves many human lives? Or should we choose ongoing history, which is interesting but also produces a great deal of suffering and death? This is a question for all human beings.

Pankieiev: You mentioned death and Putin. In one of your X posts, you described Russia as a thanatocracy.

Yermolenko: I don’t know if I invented this concept or not, but it is important to me and I think it is underestimated by external observers. My argument is that we should not consider Putin as crazy or psychopathic. Putin has his own rationality. We need to understand this rationality; otherwise, we will not be able to win against him. The rationality in Putin’s mind is actually very macabre, but it has its logic. This rationality is the notion that the power of a tyrant is primarily the power over life and death. If you can prove to your citizens, or to the citizens of your enemy, that you’re the master of death—meaning that you can really kill without moral remorse and on a large scale—then you will produce fear, and tyrants rule by fear.

Fear is produced en masse through death, and tyrants create factories of death. We will not understand Hitler or Stalin or Putin or Mao without understanding that they primarily want to conquer death and, ultimately, to own our death. We tend to think of death as a deeply personal matter. Martin Heidegger’s philosophy is built upon the idea that death is the most personal of all experiences. Nobody can die for you. You will only die for yourself. By contrast, Stalin’s message—who lived at the same time as Heidegger—was “if I own your death, then I can do anything with you. I decide when and how you will die. It is not nature or God but I, Joseph Stalin, who will decide how you die.” That message terrifies people.

I believe Putin is trying to do the same. Therefore, he demonstrates that he’s capable of killing civilians without remorse. He is capable of raising an army and sending people to their death, and nothing happens to his power. This is because people in Russia only respect a person who is capable of extreme killing—an executioner unafraid of mass murder.

This is what I call thanatocracy, which means turning death into a management tool, turning death into a tool of power. Think of contemporary Russia, but essentially all tyrannies. We can describe Nazism and Stalinism in this way. We can probably describe some of the Roman emperors in this way as well. They all understand what frightens people, and they target their power to use death as a technology.

Pankieiev: You have mentioned the concept of fear, and you also wrote that the fear of provoking Russia provokes Russia. But why is fear used as an excuse for inaction sometimes, and why don’t we see a more constructive or positive form of fear, like the fear of what will happen if we don’t help Ukraine or other people?

Yermolenko: The Western world lost a wise idea from the Cold War, as described by Raymond Aron in his classic book Peace and War: A Theory of International Relations, which was written at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Aaron understood that during the nuclear age, one of the key models of peace was peace through fear or terror. If both sides can exterminate each other but are afraid of each other’s power, then this can actually maintain peace.

After the end of the Cold War, people forgot this lesson, and others, about the dark side of human nature. This is very unfortunate. We need to read authors who openly examine the dark side of human nature. These types of authors often appear at the beginning of a century. There are many such authors from the early 20th century. People understood a great deal, and then it was all erased from memory. Freud understood that we have the Eros instinct, the instinct of life, but we also have the Thanatos instinct, the instinct of death.

We can understand the second half of the 20th century as the emancipation of Eros. But what if the first half of the 21st Century will be the emancipation of Thanatos? What if humanity now wants to emancipate and liberate the darkest elements of itself? This would be the drive to destroy, the drive for nothingness and nihilism, about which Nietzsche was telling us all the time. Therefore, I think democracies should return to an understanding that people can be good but also bad. When people behave badly, fear is a critical factor that can influence their behaviour.

Democracies do not accept that the emotion of fear can be used in this way. They believe that fear is the prerogative only of tyrants, and this is correct. But what do you do with a tyrant? How do you influence a person who tries to terrorize you? The only way to push him away is to scare him back. I think we lost this balance of fear that Raymond Aron spoke of. Russia is not afraid of the West, but the West is afraid of Russia. We have a power imbalance, and with America under Trump, this imbalance only increases.

Pankieiev: To correct this imbalance, what do you think an authoritarian regime would be afraid of?

Yermolenko: It fears losing its authoritarian power. This can happen very easily at certain moments, when time and history accelerate. This is what Putin fears. There is a Rudyard Kipling story about Mowgli and the wolves who are on the good side, Mowgli’s side. But Akela, the leader of the wolves, is what you might call a benevolent tyrant. Kipling understood how it works. If Akela the tyrant makes a mistake, he will be perceived as mistaken forever. The tyrant can’t make a mistake, because the assumption is that he never makes mistakes.

In democracies, we all make mistakes. The assumption of democracy is that we are all fallible and everyone is subject to criticism. This is good, because if you make a mistake, you can fix it. In tyrannies, the tyrant does not make mistakes, but if they do, everything they do will be a mistake. This is how people perceive tyrants.

Trump cannot truly be called a tyrant because tyrants never tolerate real rebellions. They instinctively understand, at least in practice, that they must dissuade any possible rebellion. Instead, tyrants invent rebellion and punish their manufactured rebels to serve as a warning against rebellion or even the idea of rebellion. Russia did this to the Ukrainians and other nations, and then expanded it through the show trials of 1937. The same is happening in Russia today. Why are Russian liberals often admitting to being foreign agents? What did it take to “persuade” them to face such humiliation? It seems to me that humiliating others and forcing self-humiliation are key tools in how tyrannies operate.

During Stalin’s show trials, Stalin wanted not only to punish people but also to make them admit they were traitors. In the current Putinist version, rebels, even if they are abroad, must preface their statements with the disclaimer that “I am a traitor. Do not trust me, because I am a foreign agent.” This might sound absurd, but it is how tyrannies function. If a genuine rebellion occurs and people realize that you are no longer in control, or that you have lost even a small amount of control, everything will collapse very quickly. Russia has a history of sudden collapse, as in 1917 and 1991. We must acknowledge that tyrannies are powerful, but their strength is always part of their ultimate weakness.

Pankieiev: You are living in Ukraine right now, and we are discussing philosophical ideas, but what about people and their identities? We are currently undergoing a process of change, but how is identity actually constituted and manifested? What is the state of identity right now in Ukraine?

Yermolenko: In one sense, Ukrainian society is united, but you could also say that it is divided. These divisions are unlike any found elsewhere in the world. They are not based on religion, ethnicity, or even language, but on differences in experience and actions. People are separated by how they act, whether they are serving in the military, or if they are hiding from mobilization. They are divided by whether they are supporting the army or remaining passive, whether they stayed in the country or left. If they left, they are further divided into those who are active in the diaspora and those who are passive. These divisions will greatly define Ukraine’s future.

Concerning identity, it will be interesting to see how deeply the new Ukrainian political identity penetrates society. In the first month of the full-scale invasion, everybody talked about how, by invading Ukraine, Putin is actually strengthening the Ukrainian identity of resistance. However, there is also an element of inertia. There is a great amount of entropy in people’s behaviour and development. Many people made an initial effort but eventually returned to their old ways and said, “Let’s speak Russian again, or let’s watch Russian YouTube and listen to Russian songs again.” This is happening, and Russia understands how to exploit it because they are digitally more powerful. People are not aware that if you watch one TikTok video from the Russian Comedy Club, you will see dozens more in the next few days due to the algorithm.

People have also shifted to online content. This is a media revolution related to the war, because the diversity of television programming no longer exists. In the past, television was used to convey certain messages. Now people use their phones, and what they have in their phones is a combination of many messages, to which people become very vulnerable. No one knows how to manage this situation.

I do not believe in irreversibility. I think that history is always reversible. I mean not that history is literally reversible, but that history can have reverse trends. We can never return to the past, but our progress toward the future is never linear. The Ukrainian identity is now significantly stronger than it was ten or fifteen years ago. It is very civic, in the sense that it is based on the principles of freedom, decentralization, a certain kind of anarchy, and the rejection of tyranny and imperialism, among other related values. We will see how deep the roots will be, and how, for example, the younger generation will accept this new-old identity. Will they themselves rebel against it? There are many questions, and the fight is never over.

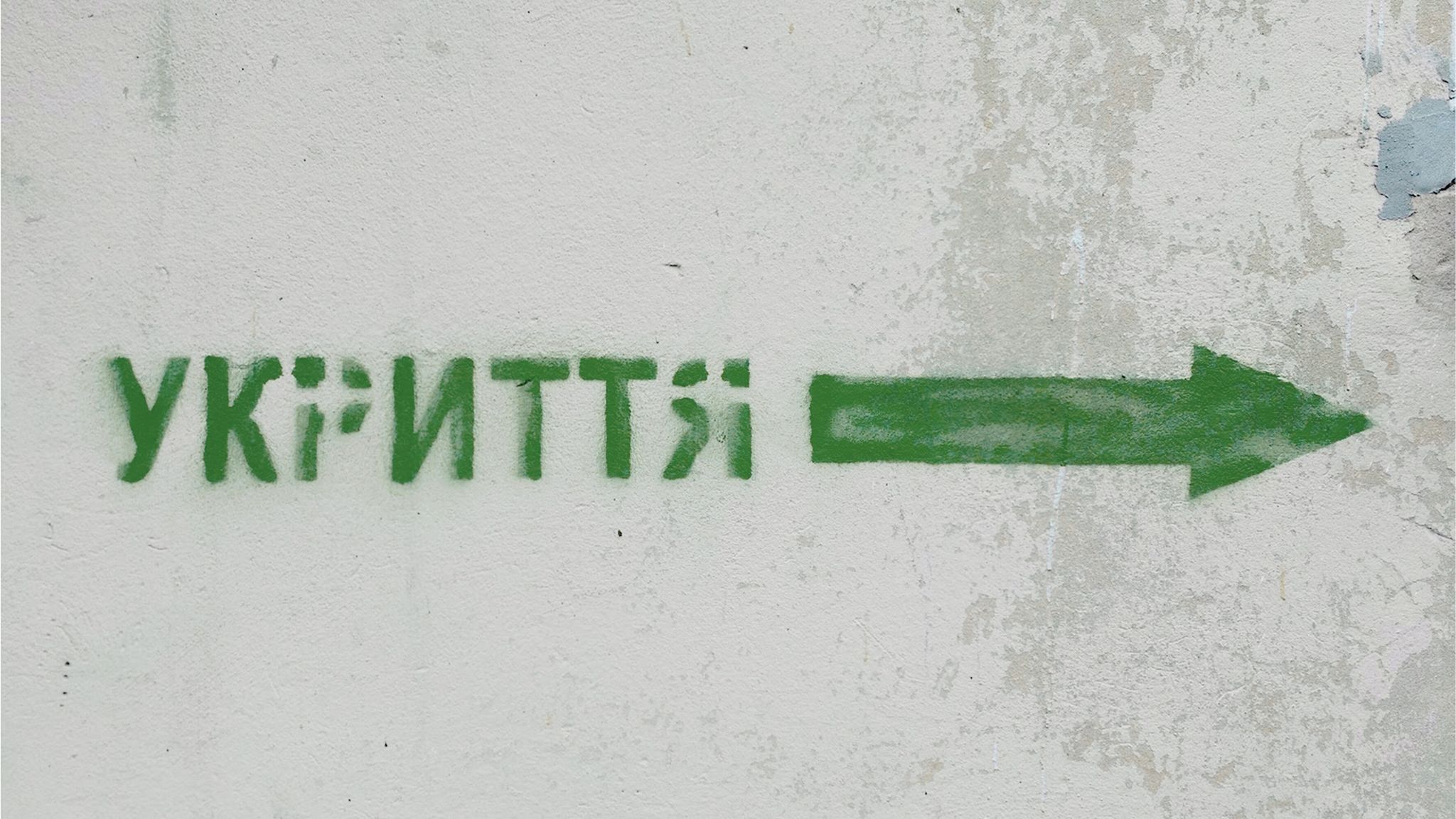

Photo credit: Valentyn Kuzan