Ukrainian education during a full-scale invasion: First year

For over a year the Ukrainian education system has been operating under martial law. After the full-scale invasion commenced on 24 February 2022, education was interrupted for several weeks and later resumed in a remote format. The experience of the two previous years (2020 and 2021), when COVID-19 imposed restrictions on the educational process, became instrumental in ensuring the stability and sustainability of studying in conditions of war, as well as made it relatively easy to switch to a remote format. Thus, despite the difficult situation of martial law Ukraine was largely able to ensure the continuity of education in schools and universities.

Ukraine’s organization of education under the conditions of the Russo-Ukrainian war is unique in many respects. First of all, the ongoing confrontation is not a civil conflict—unlike many others of the last two decades, for example, in South Sudan (2013–present), Nepal (1996–2006), Syria (2011–present), and Yemen (2015–present)—but the armed aggression of a nuclear state with huge military and mobilization potential against another state that is incomparably more modest in resources. Despite this precarious imbalance, the majority of Ukrainian children are continuing to study in schools, wherever they are. In contrast, according to a UNICEF report published in 2015, for example, internal conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, and South Sudan resulted in 13.4 million children (or almost 40 percent of all school-aged children) in these countries not being properly instructed.

In another example, every year the UN General Assembly publishes the Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict. According to the 2022 report (covering August 2021–July 2022), schools worldwide suffered 475 recorded attacks, the most being in Mali, Israel, the occupied Palestinian territory, Afghanistan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where school buildings were bombed, destroyed, or shelled.

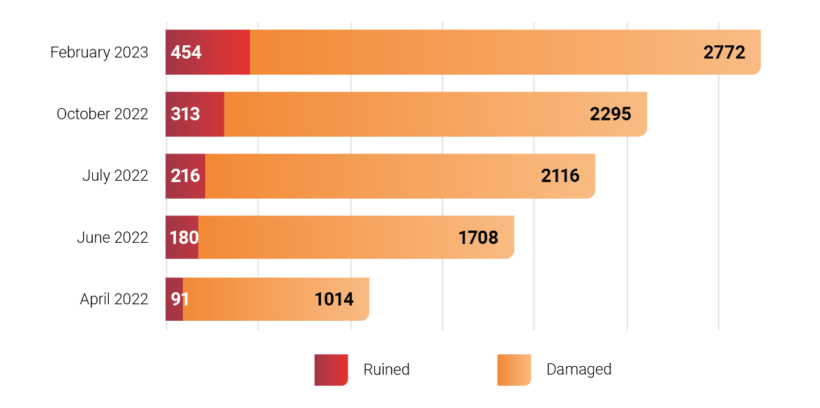

In the case of Ukraine, however, the number of attacks on Ukrainian schools in the first year of the full-scale invasion was more than six times greater than the above-mentioned statistic in multiple countries. According to the resource “Education Under Threat,” which the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine established in early March 2022, with 332 completely destroyed school buildings Ukraine’s total is almost the same as that of five countries and territories combined from the UN Report, while the number of damaged schools is incomparably more—2,860 buildings (data as of 11 April 2023). World Bank analysts provide even higher figures in their report Ukraine Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment. According to its calculations as of 24 February 2023, 454 educational institutions in Ukraine were completely destroyed and at least 2,772 were damaged. Ukrainian schools and universities continue to be destroyed on a daily basis. For example, from the beginning of the 2022/2023 school year in Ukraine, a school has been destroyed every second day.

On 28 May 2015 the “Declaration on School Safety” was adopted at an international conference in Norway. In 2019 Ukraine became the 100th signatory to this document and undertook an obligation to comply with its Recommendations on the protection of schools and universities from military use during armed conflict. Meanwhile, 2019 was the fifth year of ongoing military operations in parts of the Donbas (Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts), which led to the destruction, damage, or forced closure of almost 750 schools. The Russian Federation, which annexed Crimea and invaded the Donbas in 2014, as well as launched a full-scale invasion in February 2022, did not sign this Declaration.

Losses of educational infrastructure

Analyzing the military operations as well as the destruction of educational institutions of Ukraine since 24 February 2022, we have identified the following chronological periods.

First period: 24 February–2 June 2022. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine crossed the 100-day mark. During that time Russian troops attempted to capture the oblast centres Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, and Kharkiv but then managed to gain control only over Kherson and the Azov region cities of Mariupol, Berdiansk, and Melitopol.

All military operations were accompanied by the illegal destruction of civilian educational infrastructure. As of mid-April 2022, more than a thousand educational institutions were damaged in Ukraine, of which almost a hundred were completely destroyed. By the beginning of June the number of damaged schools and universities grew to almost two thousand.

In the first period of the war, the greatest damage was inflicted on the educational infrastructure of Kharkiv oblast. By mid-April, 49 schools were destroyed as well as the campus of Kharkiv’s Karazin National University. Vigilant Human Rights Watch employees compared interviews with displaced persons with video clips on social networks and identified attacks on two schools in the Kyivskyi district of Kharkiv. The biggest tragedy was the bombing of a school in the village of Bilohorivka in Luhansk oblast, where about 60 people were killed. These attacks by Russia were condemned by the UN Secretary General António Guterres and the British foreign minister Liz Truss. Far from the front lines, educational institutions in Ukraine’s central Kyiv and Zhytomyr oblasts were also destroyed and damaged by Russian shelling and rocket fire.

Second period: 2 June–6 September 2022. Russian troops concentrated all their efforts in eastern Ukraine, capturing Siverodonetsk and Lysychansk. In early September, thanks to a successful operation in Kharkiv oblast Ukrainian troops liberated the cities of Izium, Balakliia, Kupiansk, Vovchansk, and others.

Attacks on Ukrainian schools and post-secondary institutions continued throughout the summer of 2022. The number of destroyed and damaged buildings doubled. By July the Russians had destroyed 216 educational institutions and damaged 2,116. During the second period an average of 22 schools per day were damaged by enemy attacks, while in Kharkiv oblast fully one-third of the schools was destroyed. At the beginning of July, due to shelling in the Kyivskyi district of Kharkiv city, three floors collapsed in the main building of the Kharkiv Skovoroda National Pedagogical University.

Third period: 12 September–11 November 2022. Having lost the initiative on Ukraine’s fields of battle, the Russians changed their tactics and on 10 October attacked the entire territory of Ukraine with a large-scale missile strike (83 missiles, of which 43 were shot down) with the aim of disabling critical civilian infrastructure. This missile strike led to another wave of destruction of educational infrastructure. By mid-October more than 300 educational institutions in Ukraine lay in ruins and more than 2,500 were damaged.

Occupied Donetsk oblast suffered the most destruction of its schools and kindergartens—650 buildings. All through the summer of 2022, schools in Kramatorsk, Kostiantynivka, Druzhkivka, Kurakhovo, and Bakhmut were regularly targeted. On 10 October a massive missile strike resulted in six educational institutions being hit in Kyiv city, in addition to buildings of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine.

Fourth period: 11 November 2022–24 February 2023. In early November Ukraine regained control over Kherson, the only oblast capital that Russia had managed to occupy in this escalated invasion. In response, the Russians launched a massive offensive near the city of Bakhmut, which they have since failed to conquer (though apparently they expected to do so by the one-year anniversary of the full-scale invasion).

Ukrainian schools and universities continued to be targeted during this period. By mid-February 2022 the number of damaged facilities exceeded 3,000, with over 400 destroyed. In Zaporizhia oblast 175 educational institutions were destroyed. As in Kharkiv oblast, due to the proximity of the front line there, the Russian army could use artillery and volley fire systems, whose shelling caused significant destruction to civilian objects. Specifically, that was how the invaders destroyed the schools in the villages of Zarichne (Komyshuvakha county) and Lezghine (Zaporizhia district).

Based on the above evidence, and much more besides, it can be stated unequivocally that regardless of changes in military tactics and the front-line situation, the Russian army has been deliberately and relentlessly targeting Ukrainian schools and universities since its all-out invasion began on 24 February 2022. It is therefore beyond doubt that the longer the Russian “special military operation” lasts, the more damage and destruction will be inflicted on Ukraine’s civilian educational infrastructure. The World Bank has estimated the harm caused at $4.4 billion, and the reconstruction of destroyed and damaged facilities may cost $7.8 billion. At the Kyiv School of Economics, in December 2022 the “Russia Will Pay” project estimated the costs of rebuilding at $8.9 billion; by April 2023 this amount increased by $300 million.

People

Indisputably, the war has put a considerable strain on all participants in the educational process, who are no longer able to meet even basic requirements. The refugee crisis provoked by Russia’s indiscriminate military aggression has become the largest since the Second World War. According to the calculations of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) one year after the full-scale invasion, more than 8 million people left the territory of Ukraine, more than 5 million became internally displaced persons (IDPs), and more than 17 million are in need of urgent humanitarian assistance. Another source, the Center for Economic Strategy, claims that by the end of 2022 6.7 million Ukrainians had fled abroad.

In mid-March 2022, UNICEF estimated that Russia’s escalated invasion threatened the well-being and lives of more than 7.5 million Ukrainian children. By that time, 1.5 million children had already left Ukraine and more than 75,000 children were becoming refugees every day. According to the UNHCR, 487 children died during the first year of the all-out war.

Educators

The types of problems faced by education professionals of Ukraine depend primarily on where they are located.

Persons temporarily located outside of Ukraine

As of 1 September 2022, almost half a million of Ukrainian children were living abroad. The most dramatic aspect of this situation in the summer of 2022 was observed in Kharkiv: 120,000 out of 140,000 schoolchildren who started the 2021/22 academic year had left the city.

In the spring of 2022, almost 26,000 teachers left Ukraine due to the full-scale invasion of Russia. This figure decreased to 16,500 during the summer. At the beginning of the new academic year 2022/23, 13,000 teachers resided outside of Ukraine..

The most challenging issue that Ukrainians have faced abroad is integrating into new national educational environments. As of January 2023, two out of three Ukrainian children were not attending school in their new country of residence, because their parents were hoping for a quick return to Ukraine. Among those children who did restart their education abroad, many continued to study remotely in Ukrainian schools, which placed additional burdens on them and their parents.

Internally displaced persons (IDPs)

While many IDPs have moved from oblast to oblast but continued to stay in Ukraine, integration into a new place of residence (e.g., new schools, possible searches for permanent housing or household arrangements) and psychological support remain urgent problems for them. Often, especially in the first months of the full-scale invasion, parents and children who fled their homes due to occupation or constant shelling were living in temporarily converted shelters (e.g., school gymnasiums, kindergartens, or dormitories). It is extremely difficult to continue one’s studies in such conditions. As time went on, these constraints were somewhat resolved, but the circumstances experienced by children who had to leave their homes will still require special approaches, support, and attention well into the future.

Persons remaining behind in occupied territories (OT)

The most difficult task for students and teachers in the OT is to participate in the Ukrainian educational process, because the occupation authorities force everyone to follow Russian curricula. This has particularly been the case in Kherson oblast and in occupied Mariupol. Russian-supervised teachers must conduct special educational activities and introduce propaganda contained in documents such as, for example, “Methodical recommendations: Structural plan of lessons on the topic ‘My history’” (here translated from Russian for clarity).

Local teachers are forced to retrain in accordance with Russian standards. Those who refuse are subjected to punishment or dismissal. In their place, teachers from the Russian interior—specifically, from the Republic of Dagestan—are appointed. Also, the occupiers block access to the Internet, which makes it hard for people in the OT to communicate with the rest of Ukraine.

Regrettably, the situation looks no brighter in territories that were brought back under the control of Ukraine in the fall of 2022. In particular, in the liberated territories of Kharkiv and Kherson oblasts, humanitarian aid and mine clearance are ongoing acute issues.

At a most basic level, it must be mentioned that a sustainable educational process in Ukraine is hindered by frequent air alarms that warn of the next wave of missile attacks. Such alarms often last for more than two hours, interrupt classes, and distract students and teachers. Almost 70 percent of the university and school campuses in Ukraine have been equipped with bomb shelters, which do allow teaching to be carried out in person, albeit under constant stress. But those institutions that do not have shelters have to offer remote studies.

A further practical challenge for schools and universities was the autumn–winter period, with frequent and lengthy power outages. This led to problems with access to the Internet as well as disruptions in electricity supply and central heating in the buildings of the educational institutions.

Conclusion

Despite all the above-mentioned destruction and damage to buildings of Ukrainian schools and universities, as well as the extreme difficulty for students and teachers to access resources in acquiring and sharing knowledge, the education system continues to function for a second year now since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Educational adjustments in those oblasts of Ukraine located far from the zone of active hostilities have played an important role in the survival of the system. It hardly needs to be stated, however, that as the war continues, the problems described above will not only persist but further deteriorate.

With the help of international partners, Ukraine must prepare to endure future offensives by the Russians, which could lead to the occupation of new territories, destruction of even more schools, and further psychological pressure on educators—especially those who risk ending up under foreign rule or becoming refugees. Undoubtedly the invader will also continue its shelling and missile attacks on civilian infrastructure, which will trigger new waves of disruptions for all participants of the Ukrainian educational process.

A comprehensive government vision for the recovery of Ukrainian education needs to be developed. The current stage of hostilities allows for the initiation of reconstruction of some damaged schools in liberated territories or in places far from the front line. One of the major components of such a recovery should be to support affected participants of the educational process. For example, since the COVID-19 pandemic the issue of quality assurance and good studying practices in Ukrainian schools has remained unresolved and has only worsened with the invasion. Thanks to the help of a Canadian project titled “SURGe,” specific online tools have been developed to diagnose the loss of knowledge in mathematics and Ukrainian language among students in grades 5, 7, and 9, but this is obviously not enough.

It is also important that the Ukrainian government continues to support the students and teachers who were forced to leave their country. Despite all the demographic losses, having a large number of Ukrainian migrants in the EU offers some advantages. First of all, these people are changing the composition, or are even forming a new generation, of the Ukrainian diaspora in their new places. Before the full-scale invasion, members of the recent (post-1991) migrant diaspora in the EU were mainly unskilled labourers with dubious legal status. Furthermore, Ukrainians in the countries of their temporary stay can directly influence the decisions of foreign governments regarding supports provided to their homeland, as well as change the general cultural milieu, which heretofore often identified Ukrainians with the Russian language and overall “Russian world.” Thus, there is at least some potential for Ukrainian migrants abroad to become powerful cultural ambassadors of their country.

Translated by Ostap Kushnir.