Chronicle of the Russian war in Ukraine

Major highlights of Ukraine’s year of resistance to Russia’s full-scale invasion

On 24 February 2022 the Russian Federation started a full-scale invasion of Ukraine by simultaneously attacking the state from northern, eastern, and southern directions. A common misconception exists that this invasion signified the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war; to the contrary, the first act of aggression—as defined by the 1974 UN General Assembly Resolution 2330 (XXII)—took place on 27 February 2014. On that day, Russian soldiers in unmarked uniforms seized administrative buildings and strategic sites across Crimea, eventually leading to the occupation of the peninsula.

The first days of the escalated 2022 invasion demonstrated Russia’s ambition to conquer Ukraine in a single stroke. Columns of Russian tanks and armoured vehicles stretched from the northern border to Kyiv’s suburbs. On their path, Russians even occupied the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant and, to everyone’s shock, started digging trenches in radiation-contaminated places. Moreover, highly mobile Russian infantry units quickly flooded the southern plains from Crimea to Kherson. Western policymakers debated new sanctions to punish Russia for violating international law. Meanwhile, Western media concluded that Russia was unstoppable and its victory was a matter of time.

Ukraine responded with an unprecedented wave of civic mobilization and volunteering. People lined up to get enlisted into the army or territorial defence units. The war effort became everyone’s preoccupation and united Ukrainians of different ages, languages, religions, and ethnicities. And crucially, former showman Volodymyr Zelensky evolved into a hard-core war president: “I don’t need a ride, I need ammunition” was what he famously said to Western allies when offered assistance to flee the threatened capital.

Ukraine’s fierce resistance against the invaders bore fruit. Lacking equity in firepower, Ukrainians resorted to manoeuvrable defence—they allowed the Russians to grab some territory, dispersed and regrouped, and then attacked with high precision in the most vulnerable points. By the end of March, Russia began to withdraw from northern Ukraine.

The Russian retreat did not go unnoticed by the Western media. Many appeared surprised, some pleasantly so, but continued to argue that Russia would win. The Kremlin, they claimed, had not deployed all of its troops and was ready to yet demonstrate its full capacity. The underlying assumption was that Russia was as omnipotent as the USSR superpower—but this assumption failed to take into account the role that the Ukrainian SSR had formerly played in Soviet government, industry, and the military.

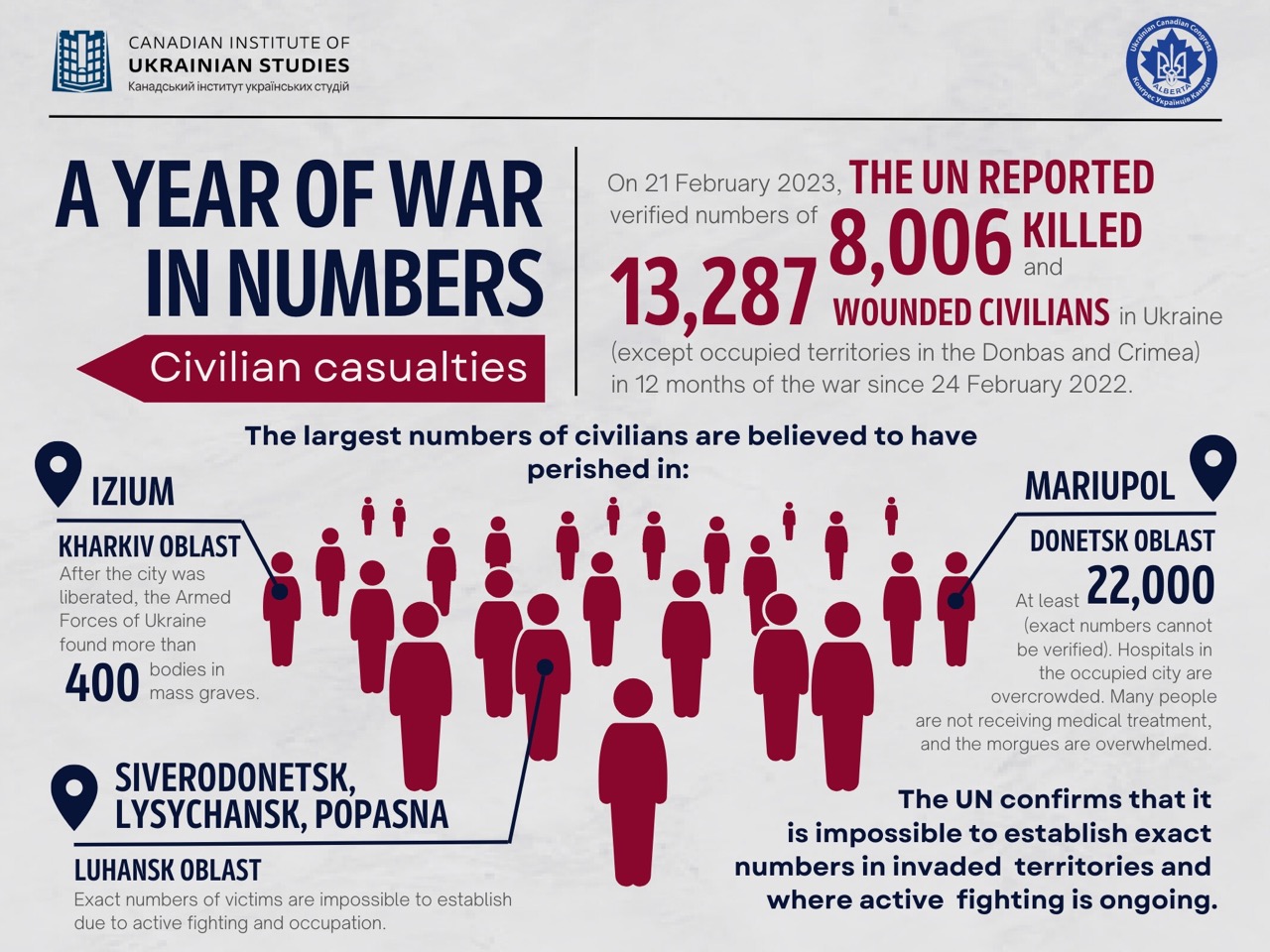

On 29 March, peace talks took place between Ukraine and Russia in Istanbul, with little progress made. The Russian side arrived with demands that the Ukrainians could not accept. The Ukrainian side believed Russia was just trying to dissemble and win time for its army to regroup. Meanwhile, the West wished for the war to end and was expecting proposals to result from the talks. However, they became irrelevant after the shock from witnessing Russian atrocities in liberated Bucha, Irpin, Borodianka, and other settlements. The perception of the war immediately changed, as the West recognized it as a matter of genocide. “We’ll let the lawyers decide, internationally, whether or not [the devastation] qualifies [as genocide], but it sure seems that way to me”—that was how US President Joe Biden reacted to the evidence.

Suddenly, global compassion turned toward Ukraine. The stubborn and fierce resistance of the Ukrainians got acknowledged. The heroic defence of the Azovstal plant in Mariupol became a legend of combat proficiency and patriotism. The world started feeling that Ukraine should be given a fighting chance. And then, on 14 April, the warship Moskva was hit by Ukraine’s missiles and sank in the Black Sea. It was the largest Russian warship to go down in wartime since the end of the Second World War and the first Russian flagship that had sunk since the Kniaz Suvorov in 1905, during the Russo-Japanese War.

The West began increasing the volumes of weapons it supplied to Ukraine, particularly light weaponry. On 7 April the US Senate unanimously passed the Ukraine Democracy Defense Lend-Lease Act. This allowed for immediate shipments of equipment, ammunition, and military assistance to Ukraine. Other Western states searched for Soviet-made weapons worldwide and purchased them for delivery to the defenders. The Western belief that “business as usual” could be restored with Russia after the war, or that peace could be achieved by sacrificing Ukraine’s territories, gradually vanished. In turn, Russia resorted to massive artillery tactics and levelled Ukrainian cities through intensive shelling.

On 18 May over 300 defenders of Azovstal received orders to save their lives and stop armed resistance. Rounds of hard negotiations began to bring Ukrainian soldiers back from Russian captivity. A few days earlier, on 14 May Ukraine’s Kalush Orchestra won the Eurovision contest with their song “Stefania,” a masterpiece of wartime music. In turn, Ukraine’s migrants and refugees were noted to be boosting the economies of host Western European countries. They opened new businesses and covered labour shortages, making them often seen as welcome in the local societies. In general, understanding of the Russo-Ukrainian war in the West became more nuanced. The war stopped being a regional conflict but rather a continental if not global one. It was not going to finish soon and its repercussions would be felt for decades. Ukraine was proving not to be “an artificial state,” as Russians had often portrayed it, but a strong and conscious political nation willing to defend itself from external aggression, and its liberal democratic values from revisionist attempts of authoritarian Russia.

In late May, after three months of active fighting and struggle Ukrainians continued to believe in the eventual victory of their army. A survey conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology demonstrated that 82% of Ukrainians rejected the idea of yielding any territory to Russia, while 61% supported “opposing Russian aggression until all of Ukraine, including Crimea, is under Kyiv control.” At the same time, according to a Levada Center survey in Russia, an overwhelming 77% of Russians supported the continuation of the invasion of Ukraine till their complete victory.

In mid-June, the first High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) arrived on the battlefield. Russia’s blanket shelling offensive became less intense as Ukraine’s HIMARS strikes interrupted the supply of arms, spare parts, and fuel to its avant-garde units. On 23 June the EU recognized Ukraine as a candidate state for membership. It was one of the major political events in Ukraine’s modern history, ending thirty years of vacillation. Candidate status also became a symbolic promise of a dignified future that motivated Ukrainians to endure the calamities of war. On 30 June Ukraine’s army wiped out the Russian garrison at Zmiiny (Snake) Island and strengthened its control over the Black Sea littoral. That being said, a few days earlier, after prolonged fighting and intensive artillery bombardment, Russians managed to overrun Siverodonetsk city in the Donbas. Among Western countries a common understanding gradually solidified that Russians must be tried for their crimes of aggression in Ukraine. New rounds of sanctions against Russia were also introduced.

In mid-July it became clear that a few dozen HIMARS delivered impressive damage to the invaders were insufficient to change the pace of the war decisively. Western partners acknowledged that more and heavier weaponry was needed. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s agricultural products returned to global markets through unlocking maritime grain exports under a UN-brokered deal. Before the invasion Ukraine was providing 10% of the world’s wheat, 16% of its maize, and roughly half of its sunflower oil. The export mechanisms were brought back on 22 July. Meanwhile, Russia continued committing war crimes. On 29 July a building near Olenivka, Donetsk oblast, that housed Ukrainian prisoners of war was destroyed, killing 53 people and leaving 75 wounded. Russia did not allow international observers to reach the site of the tragedy immediately. The most probable hypothesis behind the massacre was that Russia had purposely orchestrated it, as many of the killed POWs were defenders of Azovstal.

On 9 August Ukraine attacked the temporary enemy airbase in Saky, occupied Crimea, which had a profound psychological effect on Russians. While this attack did not change the balance of power between the two sides, it demonstrated Ukraine’s newly acquired capabilities of hitting Russia’s rearguard. As for the front lines, Russia’s human losses became the highest since the Second World War. The Pentagon suggested that “the Russians are probably taking 70 or 80,000 casualties in less than six months.” In this light, skepticism about Russia’s battle prowess started growing in the West. Instead, Ukraine was believed to be gaining the initiative thanks to its exceptionally effective utilization of supplied weaponry. Frederick B. Hodges, a former top US Army commander in Europe, said that Ukrainians were “MacGyvering” solutions to warfare: engineering simple, improvised contraptions to secure the best outcomes under unfavourable circumstances.

In early September Ukraine launched a daring counteroffensive in the Kharkiv oblast. Breaking through Russia’s lines, moving with an impressive speed, and capturing hundreds of items of Russian equipment along the way, Ukraine liberated over 500 settlements and recovered 12,000 square kilometres within three weeks. This success proved to the West that Ukraine was serious about defeating Russia. On 21 September Ukraine and Russia agreed to the biggest prisoner exchange of this conflict: 215 Ukrainian POWs, including commanders of the Azovstal defenders (though some of them had to stay in Turkey as their return to Ukraine was prohibited). On 30 September, in a symbolic but powerful move, Volodymyr Zelensky announced a bid for fast-track NATO membership. The President believed that Ukraine and its army had achieved the necessary standards and de facto could join the Alliance under an accelerated procedure. However, this bid caught the Western partners by surprise; they did not share Zelensky’s enthusiasm.

In October Ukraine continued its counteroffensive. The city of Lyman, a major logistical nexus in the east, was liberated on the first day of the month. That opened a window of opportunity to advance even deeper into Russia-occupied territories. On 8 October Ukraine blew up the Kerch Strait Bridge to Crimea. This attack on Vladimir Putin’s ballyhooed “pet project” had profound military and symbolic implications. At the same time, it is not known precisely how Ukrainians managed to strike the bridge. Its partial destruction signalled to the Russian elites that they could lose the war. In response, Russia amplified its nuclear blackmailing of the West. It also intensified attacks on Ukraine’s critical and civilian infrastructure with missiles and Iran-made drones. Russians seemed to expect that Ukrainians would lose their fighting spirit if threatened with the absence of heat, electricity, and water on winter’s eve. However, the effect was the opposite: Ukrainians became even angrier with Russia and their motivation skyrocketed. On 7 October the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties, which had been documenting Russian war crimes, co-won the Nobel Peace Prize. Meanwhile, international investigators again made shocking discoveries as they documented accounts of detentions, torture, collaboration, property theft, and missing relatives in the recently liberated Kharkiv oblast.

On 11 November Ukraine liberated Kherson, the biggest city and the only oblast capital that Russia had managed to conquer since February. Under months-long grinding pressure, the invaders were forced to retreat from the west bank of the Dnipro River and give up their positions in and around the city. The liberation of Kherson became another major defeat of the Russian army in this war. In the West, speculation arose about the possible partition of the Federation in the aftermath of the war. In conjunction with a malfunctioning economy, the weakened regime was at risk from the possibility of frustrated Russians being pushed to take to the streets, perhaps even with arms, and of some federal subjects gathering courage to opt for greater self-rule; leading regions for the latter included Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Chechnya, Dagestan, and Sakha. At the same time, as of late November 2022 Ukraine’s authorities estimated that around 8 million citizens, constituting 20% of the pre-February population (i.e., excluding occupied Crimea and the Donbas), were located abroad. Such a massive population displacement was recognized as a future existential challenge for Ukraine.

In December the legendary defence of Bakhmut caught the world’s attention. The Ukrainian army successfully endured a powerful wave of attacks that had started in August. Regardless of Bakhmut’s minor strategic importance, Russia decided to throw its best units at it for the sake of gaining a victory that had been lacking for so long. The Wagner private mercenary group constituted the backbone of the offensive. However, no considerable progress was achieved. In return, on 26 December Ukraine executed a successful drone attack on a Russian airbase in Engels, where strategic bombers had been stationed. This strike was dramatic, because Ukrainian drones had reached targets deep in Russian territory, around 700 kilometres from the front line. Neither Russia nor Ukraine’s Western partners expected it to be capable of such long-range shots. Meanwhile, Western media started actively discussing the fact that the northern, eastern, and southern parts of Ukraine had become the world’s most heavily mined territories. At the same time, to bring Russian soldiers and their commanders to justice—the major suspects behind this mining—the international community would need to develop and enforce case-specific mechanisms. Otherwise, within the framework of existing extradition procedures it would be impossible to prosecute war criminals unless they left Russia of their own accord.

Another significant development of the month was President Zelensky’s visit to Washington, DC, on 21 December. That visit became one of crucial historical, symbolic, and military importance. Ukraine was promised the most high-tech Patriot air defence systems. After a meeting with President Biden at the White House, both presidents held a joint press conference. They agreed that the West had so far not provided sufficient support to Ukraine because European allies were “not looking to go to war with Russia. They [were] not looking for the Third World War.”

January 2023 started with good news for the government in Kyiv. On the fifth day of the new year, Washington announced that it would send Bradleys, the US Army’s primary infantry fighting vehicle, to Ukraine. On the same day, Berlin declared readiness to send its Marder armoured fighting vehicles. A day earlier, Paris had confirmed sending its AMX-10 RC. All three types of vehicles are highly manoeuvrable and built around powerful guns that can damage if not destroy heavy tanks. And in late January, after nearly a year of requests and waiting, Ukraine was finally promised Western battle tanks. Washington confirmed that it would send at least 30 Abrams M1s to Ukraine. That decision came as a reaction to the reluctance of the German government to send its Leopard 2s before any of its Western coalition partners set a precedent. At the same time, the UK promised to equip the Ukrainian army with its Challenger 2 tanks. In light of such news, Russia became even more aggressive and, benefiting from high numbers of recently mobilized soldiers, conquered the town of Soledar, north of Bakhmut.

In early February the Western partners started pondering sending jet fighters to Ukraine, particularly the F-16 and Eurofighter Typhoon. Such equipment, alongside heavy tanks, had been requested by the government in Kyiv since the first days of the invasion. Increasing control over the sky has always been a priority for Ukraine’s army, because the Russian command has waged this war regardless of the costs. Thus, deploying F-16s and Typhoons would help to keep the front lines and defend critical national infrastructure against drones and missiles. On 4 February Italy and France promised to provide the SAMP/T-MAMBA air-defence system to Ukraine, which can shoot down ballistic missiles. On 8 February President Zelensky commenced a quick tour across European capitals—London, Paris, and Brussels—to further promote Ukraine’s defence cause. Mid-February saw the reactivation of warfare as Russia went on the offensive in numerous locations. Meanwhile, according to the Pentagon, Russia is presumed to have had over 180,000 of its soldiers killed or wounded in less than a year.

This report was prepared for the Ukrainian Canadian Congress—Alberta Provincial Council by the analytical magazine Forum for Ukrainian Studies, a project of the Contemporary Ukraine Studies Program at the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta.