Lysiak Rudnytsky’s prescience: Ukraine’s political turbulence and trauma of a “non-historical” nation

In the mid-2010s, researchers from the College of Europe in Natolin arrived at an interesting conclusion: contemporary Ukrainians are prone to political nonconformism.

If we look at the past three decades in the history of Eastern Europe, Ukraine may safely be placed at the top of the chart of “unstable” states. First was the student-led Revolution on Granite in the 1990s. The outcome of that revolution was a resignation of entrenched high-ranked Soviet officials under the pressure of public opinion. Then, if we skip the 1999 anti-Kuchma protests, the next big upheaval was the Orange Revolution in 2003–04. It led to a rerun of the presidential election and eventual reboot of the government. Finally, the massive and blood-soaked EuroMaidan, or Revolution of Dignity, happened in 2013–14—which, once again, led to a drastic change in Ukraine’s ruling elites. All three revolutions were of unprecedented regional magnitude and became a factor in the foreign policy of the EU, Russia, and US.

Remarkably, these developments were anticipated in the 1960s by a Ukrainian historian, Professor Ivan Lysiak Rudnytsky. He portrayed the forthcoming waves of political nonconformism as an outcome of the historical gaps in Ukrainian national awareness and statecraft. He defined Ukraine as a “non-historical” nation: “‘Nonhistoricity,’ in this meaning, does not necessarily imply that a given country is lacking a historical past, even a rich and distinguished past; it simply indicates a rupture in historical continuity through the loss of the traditional representative class.”

Reading Lysiak Rudnytsky’s article “The role of … Ukraine in modern history” today, one is struck by its relevance in explaining the processes occurring in contemporary Ukraine. It is hard to believe that the article appeared more than half a century ago.

According to Lysiak Rudnytsky, over the centuries Ukraine failed to elaborate a refined tradition of governance, and neither did it nurture any conscious national elites. However, unquestionably there have always existed visions of justice and order among its people. What is taking place in Ukraine today is an attempt to define and institutionalize numerous visions of justice and order that often collide. All three recent revolutions are related to the fact that people and elites-in-formation have been striving to develop an indigenous Ukrainian tradition of governance, but they do not understand clearly how to do it or what they are aiming for.

In other words, contemporary Ukraine is still undergoing the processes of formation of its national uniqueness and a feeling of state. These processes are painful, uneven, and chaotic. One reason for this is Moscow’s belief in its right to meddle into Ukrainian affairs along with Kyiv’s lack of ability—or even an unwillingness—to eliminate that meddling. Another reason is the divisive cultural heterogeneity of Ukrainian society, whose members have yet to learn the meaning of being a political nation. In the 1960s, Lysiak Rudnytskystated that “the central problem of modern Ukrainian history is that of the emergence of a nation: the transformation of an ethnic-linguistic community into a self-conscious political and cultural community.” This statement is relevant even today.

Cultural heterogeneity has always influenced Ukraine’s national identity and statecraft. Throughout history, Ukraine’s geographic location in the “corridor” between Europe and Asia naturally contributed to the decentralization of governance and to social diversity. In this light, Lysiak Rudnytsky emphasizes the varied political and economic experience acquired by different regions of Ukraine under the rule, at one time or another, of Poland, Hungary, Turkey, and Muscovy. He also points at the variable historical development of Ukraine’s different regions; for instance, the Black Sea steppes became populated only in the early eighteenth century, which made their political culture different from that of both Right-Bank (Polish-ruled) and Left-Bank (Russian-ruled) Ukraine. Finally, he highlights the connection—or relative absence—of the Ukrainian national elites to the common people, the collision of “nationalist” and “populist” political thinking, Cossack[1] liberties and the serfdom experience, and other diversifying factors. All of these had their own particular significant influence on the academic discussions of Ukraine during Lysiak Rudnytsky’s time in the 1960s. And as of today, they continue to underlie Ukraine’s lack of “feeling of state.”

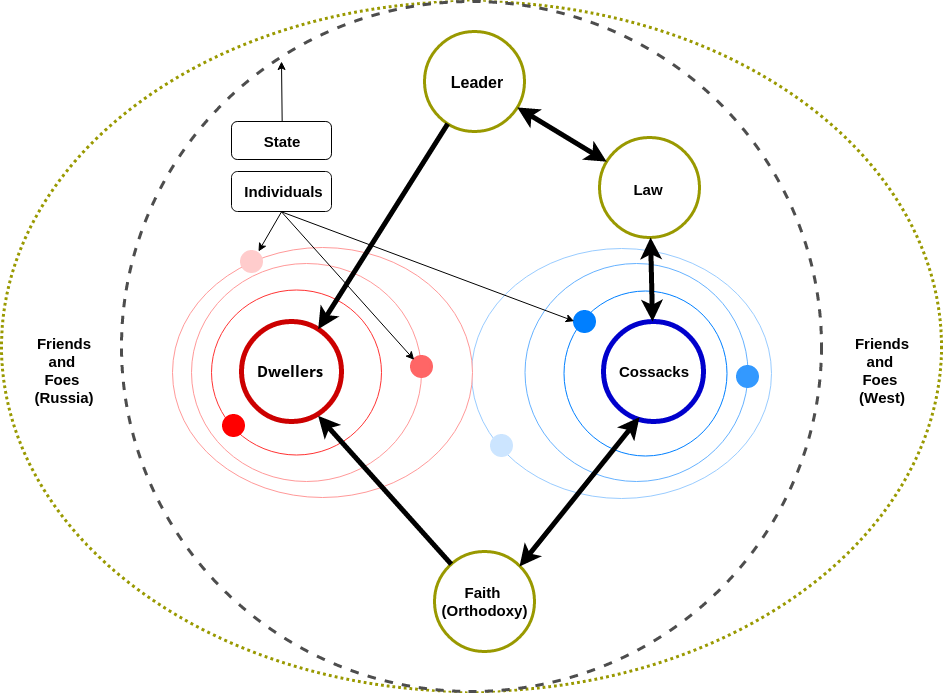

Connecting Lysiak Rudnytsky’s “non–historical nation” approach to Ukrainian political symbolism, which I am currently researching, we also find an interesting albeit unexpected regularity. The revolutionary spirit of contemporary Ukraine stems from a dichotomy between passive residents and social activists, between conformists and challengers, between symbolic “dwellers” and “Cossacks.” On the one hand, we may observe a large number—if not the majority—of Ukrainians who would like to get along with any system of governance, even if it is oligarchic or corrupted. On the other hand, there exists a group of activists who constantly challenge the established systems and demand they be updated or re-designed. The revolutions then occur when the symbolic “dwellers” start supporting the symbolic “Cossacks” in their struggle for change. This dichotomy has much to do with the disrupted formation of unitary national identity and emotion-based republicanism of Ukrainians, so common for the geographic area. This dichotomy is also responsible for band-wagoning in policy-making and for the emergence of multiple poles of power.

I understand the term multiple poles of power to entail the short-term and irregular appearance of leaders who gain grassroots support from selected Ukrainian communities. As a rule, such leaders lack proper governing culture or competencies, even though they may be recognized as trustworthy authorities. What is difficult is that such leaders and their supporters often advocate uncompromising values and, as a consequence, limit their co-operation with other actors. These limitations hamper the overall coherency of nation-building processes and increase their decentralization, but nevertheless they do contribute measurably to nation building as such. Under the right circumstances, everyone may become a leader and construct his or her pole of power—from an oligarch who seeks regional support to an inspired poet-patriot or commander of a voluntary battalion.

This trend was noted by Lysiak Rudnytsky with respect to the late nineteenth-century Ukrainian intelligentsia. He claimed that numerous forces competed and influenced the formation of the Ukrainian nation: “for instance, the activities of the Ukrainian zemstvo or those of the Ukrainian branches of ‘All-Russian’ revolutionary organizations, from the Decembrists, through the Populists, to the Marxist and labor groups at the turn of the century.” In a word, decentralized government and multiple poles of power have always been characteristic of Ukrainian political culture.

[1] Here understood as free people who rejected oppressive (non-indigenous) rule of their states, moved to unpopulated frontiers, and defended those frontiers. Cossack political culture played a crucial role in Ukrainian nation building.

As a recent development, the EuroMaidan has provided some great examples of unsustainable leadership. In the aftermath of the revolution, some of the street commanders decided to join Ukrainian governing structures. One such individual was Dmytro Bulatov, a key figure in the “AutoMaidan” vehicle-based satellite protests. On February 2014 he was appointed Minister of Youth and Sports of Ukraine, and served up to December 2014. During that short term, Bulatov introduced no innovative reforms, although he tried hard and was very motivated. The same applies to Mykhailo Havryliuk and Volodymyr Parasiuk, elected as MPs in autumn 2014. Having proved themselves as charismatic revolutionary hotheads, they came to the Ukrainian parliament to represent the values of the Maidan. However, they both lacked an understanding of legislative affairs, which lead to their eventual loss of authority and devolution into controversial figures.

Apart from domestic unsustainabilities, Lysiak Rudnytsky also points to the havoc wrought on Ukrainian statecraft by the Russian political tradition. Proximity to Russia prevents Ukraine from truly overcoming its “non-historical” trauma and literally provokes new revolutions against the centralized rule so frequently “exported” from Moscow. According to Lysiak Rudnytsky, Ukraine used to be “an organic part of the European community of nations, of which despotic Muscovy-Russia had never been a true and legitimate member.” This difference makes these two states incompatible with respect to good governance and a healthy society. To highlight this, Lysiak Rudnytsky cites the nineteenth-century Ukrainian political philosopher Viacheslav Lypynsky, who claimed that “the basic difference between … Ukraine and Moscow does not consist in the language, race or religion … but in a different, age-old political structure, a different method of organization of the elite, in a different relationship between the upper and lower social classes, between the state and society.”

As a further example, consider the former Donbas strongman and disgraced Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, who attempted to introduce Russian-type centralized governance in Ukraine in 2004 and 2014. He failed in both these attempts, stopped by the symbolic “Cossacks.”

That said, there has always been a different group of Ukrainians—the symbolic “dwellers”—who are mesmerized by the Russian civilizational power and magnitude. This has allowed for the circulation of “Little Russia” narratives and the traumatic subordination of the Ukrainian nation to the delusive “Big Brother.” Lysiak Rudnytsky put it bluntly, that many Ukrainians desire to feel affiliated to the Russian culture, which inevitably hampered the construction of an indigenous Ukrainian history and national identity.

In light of the pervasive Russian presence, Ukrainian leaders of the nineteenth century spoke cautiously about their national and statecraft initiatives. At best, they advocated the transformation of the “empire” into a “loose federation.” The ideas of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius are eloquent here. Their cautiousness was employed not to irritate the autocratic government and, hopefully, to gain support among moderate Russians. Today, some of the Ukrainian leaders are following the same logic. They want to “speak to Russia,” appraise its power, and avoid its getting “irritated.” They are even ready to seek compromises at Ukraine’s expense, as recent policies of President Zelensky’s Administration might have demonstrated.

Therefore, it appears that the future of contemporary Ukraine is destined to be turbulent. No other realistic scenario exists for a young, “non-historical” state squeezed between two civilizational extremes: Russia with its Asian-centralized tradition of governance and Europe with its individualism, liberties, and entrepreneurship. To make things even worse, Ukraine’s statecraft is practiced by inexperienced leaders, in conditions of pressure by an aggressive Moscow and over-boosted expectations of its own politically immature society.

The future of Ukraine will be full of U-turns, both peaceful and not.

P.S. These and other results of my research on Ukrainian national identity are presented in my book Ukraine and Russian Neo-imperialism: The Divergent Break https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781498558631/Ukraine-and-Russian-Neo-Imperialism-The-Divergent-Break

=====

Ostap Kushnir is an assistant professor at Lazarski University (Poland) and a lecturer with Coventry University programmes (UK). He holds an M.A. in Journalism from Odesa Mechnikov National University, an M.A. in International Relations from the University of Wales, and a Ph.D. from Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń. His academic interests include geopolitical and identity-forming processes in Central and Eastern Europe, specifically in Ukraine and the Black Sea region. He is the author of Ukraine and Russian Neo-imperialism: The Divergent Break (2018) and editor of The Intermarium as the Polish-Ukrainian Linchpin of Baltic–Black Sea Cooperation (2019).